By Kate Kingsbury

The Mexican State’s relationship with the region of Oaxaca, is tenuous, unlike the Catholic Church whose rapport with locals has long had importance in the region despite its troubling history. Yet Indigenous Oaxacans, far from following the Church’s edicts rigorously, continue to adapt and adopt Catholicism in their own unique ways, in forms that speak to their pre-Hispanic past but also reflect the present difficulties they face in the post-colony. Santa Muerte is a sui generis sacred syncretic saint. Santa Muerte devotion has become a means for Indigenous women to empower themselves in the face of inequity, state exclusion, discrimination, and gendered violence, thereby creating new ways of being modern Mexican mothers.

Oaxacan Riches: Bën zaa

Separated by the Sierra, three large mountain ranges, from its Northern neighbours, the state of Oaxaca has long been disparaged by other Mexicans, who perceive the state as backward. Adhering to neo-colonial paradigms, they erroneously blame the region’s meagre economic growth on the many Indigenous groups who inhabit the region. Obviously the reasons for the state’s sedate socio-economic development are complex. The poverty endemic to the region has often struck me. I recall last winter: I had stopped on a steamy tropical night on my way home from my local Santa Muerte shrine in rural Oaxaca, to buy a cool drink from a makeshift stand by the side of the road. It seemed to jut out of the jungle. A Zapotec woman ran the informal store which was also her home. This dwelling without windows, without doors, consisted but of a rickety structure made of wood, metal supports and a basic corrugated iron roof. I handed the store owner a few pesos for a coconut, which she hacked open for me to drink. As I lifted my head to sip the sweet liquid, I suddenly became aware of a little girl and a small boy. They were stirring, thumbs in their mouths, asleep on nothing but a threadbare blanket on a dirt floor in that makeshift hut by a dusty road. Their mother, noted my gaze absorbed by the tiny figures exhaling and inhaling those short, wispy breaths that only children ever make, and said: ‘from here I can watch over them’. Indigenous children need watching over, as like their mothers, no one else watches over them.

The poverty of Oaxaca may make it seem deficient to those Mexicans who live in the so-called developed North, but the state’s wealth is ineffable in terms of culture. Oaxaca is the most diverse of all Mexican states, home to 16 distinct ethnic groups, as well as African communities whom intermingled with local peoples to form unique traditions: Afro-Mexican dialects, dances, musics and ways of being. Economic growth indices cannot represent the richness of this region, the cultures, cuisine, languages nor describe the generosity of the people I encountered.

In the region where I have predominantly spent my time, the Zapotec or Bën zaa, as they call themselves, are the most populous Indigenous group. Zapotec is in fact an exonym which comes from Nahuatl, meaning inhabitants of the place of the sapote, referring to a local fruit. The endonym, Bën zaa means people of the clouds. I will use both terms interchangeably as a mark of respect. Bën zaa culture and dialect differs depending on whether they inhabit the mountains, valleys, or coastal regions. Generally, central villages or towns form the nexus of their society which has an agricultural base. The staple crops are corn, beans, and squash. Some Zapotec also hunt, fish, and gather wild foods. Bën zaa history stretches back to at least 500 BCE, although much of their material culture was plundered by the Spaniards, and religious items iconoclastically annihilated by Catholic clergy. Archaeological exploration of the ancient cities and structures that remain attests to a culture that was highly sophisticated boasting fine arts, advanced architecture, a writing system and complex engineering projects.

Mitla, Oaxaca’s sacred center in pre-Hispanic times

A State of Exclusion: Indigenous Realities

The Mexican State has long regarded Oaxaca as an impediment to development. Indigenous women, such as the Zapotec mothers I met, are perceived as problematic women whose pregnancies must be controlled according to state policies and who must be taught to be ‘good mothers’. The Mexican state is presided over by affluent, light-skinned mestizos whose luxurious lifestyles and educations abroad and at home in leading establishments entail they are completely divorced from Indigenous realities. The national illiteracy rate in Mexico is 8.4 percent, however among Indigenous peoples the illiteracy rate is 44 percent. Figures from 2014 suggest that only 27 percent of Indigenous children graduated from high school. Furthermore, only 3 percent of indigenous peoples attended institutions of higher education.

Whilst conducting my research, I often wanted to ask people to spell words that were unfamiliar to me so that I could write them down for my field notes. Yet many of the new friends I made- and I call them friends, not field subjects, as they became dear to me during the weeks we had together- could not write. Some could not draw maps either, when I asked them to direct me to an unknown location and gave them a pen and paper they drew inchoate forms. I realised that I was at fault, map-drawing is not an inherent ability. Instead, they taught me that as a gringa I was incapacitated by my lack of knowledge of nature, because ‘it is located next to the large tamarind tree’ meant nothing to me.

The Government has made sparse efforts to promote Indigeneity, does not protect these communities nor provide them with adequate services necessary for their well-being. If anything the State has in fact aggravated conditions for numerous Indigenous populations. Many Indigenous Oaxacan men and women have had their social movements criminalised, their land militarised, have very few rights and basic access to healthcare and other support services. Indigenous women are at the bottom of the hierarchy. They are economically exploited, with limited opportunities to support themselves financially. Subject to racism, due to their dark complexions and sexism, their triple burden entails they live in a State where impunity is the reaction to crimes against them. Gendered violence and femicide are a tragic part of the quotidian. Young Indigenous girls are frequently snatched and sold into prostitution. Indigenous children are at risk from organ traffickers who prowl areas where children are unsupervised kidnapping and killing Indigenous infants so as to sell their organs on the black market for thousands of dollars.

I became particularly cognisant of the disparity between Indigenous spaces of exclusion and inclusion on Christmas eve. Whilst waiting for the local fiesta del pueblo (village party) to begin, I sat in a crowded, dingy bar. Located in a palapa, an open-structured building, made from wooden supports with a thatched roof of dried palm leaves, the rustic charm had drawn me in. But my Western mindset entailed that I nearly left. The bar reeked of urine emanating from the latrine below. The odour intermingled with the salty scent that susurred in from the sea, fusing into a fusty fetor. A trail of ants crawled up the wall adjacent to me and I wondered if I was the only one to notice these things, having grown up in the West where spaces are sanitised, homogenised and febreezed.

I sipped my mezcal surrounded by dark-complected, dark-haired, small-statured locals dressed simply in basic t-shirts and worn trousers. From conversations with such people, I was by now aware that most of these people live on less than 7 dollars a day, often dwell in palapa-like structures which may not have drainage, nor access to running water, nor electricity. Locals are considered wealthy if they are among the few that can afford a basic car, a washing machine, and a fridge. A television blared on the wall of the bar. Tall and limber Mexican pop stars with light hair, fair skin and luxurious clothes streamed to the local crowd. One minute the pop stars were driving their Mercedes, the next against backdrops of marble-clad rooms with plush velvet sofas, they served champagne in crystal glasses with bejewelled hands.

Although Indigenous locals are included in these spaces through the visual transmission of these images, they are entirely excluded from any socio-economic opportunities that could ever lead them to indulge in such lifestyles. In the field area where I conducted my research, I don’t think you could buy a velvet sofa if you tried! Even when exceptionally an Indigenous person makes it to the big screen – as in the rare case of Yalitza Aparicio, the Oaxacan Mixtec actress who starred in the Oscar-nominated film Roma– they face backlash and racism from Mestizo Mexicans who denigrate their dark complexions, afterall ‘Indio’ or Indian (meaning stupid or low-class) is one of the most common derogatory epithets in Mexico, revealing the neocolonial paradigms that sully social-cultural constructions in the post-colony.

A History of Hostility: Death Deities as Demons

Despite the hostility towards them, Indigenous people have an indomitable pride and are aware of their unique history. Many Indigenous social organisations have been established to ensure freedom of expression and to resist oppression. Yet numerous have been banned by the State. Religion is a quintessential part of the quotidian and in the absence of local organisations and social support systems, religious movements remain central to communities also empowering Indigenous peoples at an individual level. Most Indigenous peoples identify as Catholic and Evangelical Protestant, yet many practice their faith in a way that radically differs from Biblical scripture or papal precepts. The Catholic Church has a troubled history in the region, yet unlike the Mexican State whose authority rests on force and paternalistic intervention, I noted that Zapotec locals do not question the disconcerting history behind their Catholic beliefs and praxes, rather they envision them in their own terms.

In 1519, Hernan Cortés entered the Mexica capital of Tenochitlan to meet the Aztec ruler Montezuma. Following two years of bloody war, the capital fell to the Spanish who slice by slice, seized more and more of this fecund land and its bounties of gold with what Jared Diamond summarised as ‘guns, germs and steel’. During this time and in the years to come, Indigenous peoples were decimated, many populations being reduced in genocides where 60% and often up to 80% of autochthonous populations perished. Christianity comprised a crucial component of the colonial conquest of Indigenous peoples, conquering ‘hearts and minds’. In 1523, the Catholic Church began to send missionaries, commencing with the Franciscans in what is now Mexico City. Much further south, in Oaxaca, among the Bën zaa populace, the Dominicans dominated, doing double duty: disseminating the word of their male, monotheistic god whilst destroying Indigenous doxa. Peregrinating from town to town they gathered what they deemed to be demonic idols from Indigenous temples, breaking and burning them in behemothic bonfires. Although some codices survive, many sacred texts were also annihilated. Zapotec caught still practicing their Indigenous faith were incarcerated and tortured until apostasy.

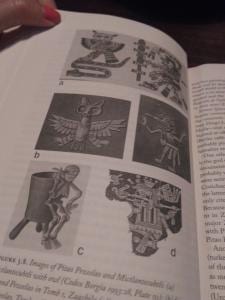

We have scant knowledge of pre-hispanic Bën zaa beliefs and practices. Aside from assumptions based on archeological digs, the only other sources of information academics have access to are documents penned in the 16th and 17th century by Spanish priests. These consist of colonial records that were the bitter fruit of forceful interrogations of those imprisoned for practicing their faith. As such they are contaminated by colonial, Christian conceptions which are crudely sexist as well as racist. Nevertheless, they intimate a polytheistic pantheon of deities both male and female, chief among which were death deities. Among the Aztec, Mictecacihuatl and her husband Mictlantecuhtli, who presided over the underworld, Mictlan, were but minor deities in a long list where Quetzalcoatl, god of life and wind and Huitzilopochtli god of war, the sun, and sacrifice eclipsed the death deities. However amongst the Zapotec, death deities were the ne plus ultra of spiritual beings who overshadowed all others in a large pantheon of what would appear to consist of at least twenty core gods and goddesses.

Catholic priests recorded in their colonial reports that the Bën zaa were members of a cult of death, particularly popular during the classic period which lasted into the 17th century and emanated from Mitla, a sacred center, into remote Indigenous communities. Today still, even centuries after conquest veneration of the dead is still entrenched in Oaxacan culture, with its culmination being the Day of the Dead celebrations in November. The death deities central to Zapotec religion were the goddess Xonaxi Quecuya, (sometimes referred to as Ponapi Quecuya or Xonati Huilia) and her husband, the god Pitao Pezeelao (also referred to as Coqui Bezelao and other variants in clerical records). According to Spanish records they presided over the underworld. Priests erroneously transmogrified the deities into demonic entities. For example Fray Juan de Cordova described Xonaxi Quecuya as ‘la diosa del infierno, la mujer de Lucifer, a quien sacrifican por los enfermos y por los muertos’ (the goddess of hell, the wife of Lucifer, who is sacrificed to for the infirm and the dead) and Pitao Pezeelao as ‘el dios del infierno…diablo grande’ (the god of hell, the big devil). The phallocentric emphasis on the goddess Xonaxi Quecuya as a ‘wife’, and the satanocentric lexicon utilised to systematise these sacred beings reveals more about the colonial, clerical weltanschauung than it does about Bën zaa belief and practice. Nevertheless, these records do allow us to ascertain certain key elements.

Indigenous Thanatology:

From colonial and clerical reports we can confirm that death deities were the principal figures in a large pantheon of Zapotec gods and goddesses. The archaeological and archival work of Michael Lind and Jean Starr also affirms that sacrifices were made to Xonaxi Quecuya and her husband Pitao Pezeelao. These consisted of fowl, possibly human sacrifices in pre-Hispanic eras, copal incense was burnt before the deities and later with the introduction of votives by the Spanish, candles lit to them. The Bën zaa made oblations for health and healing, as well as upon death. Nobles in particular were honoured in Mitla, the sacred centre, with grand celebrations in homage to these deities. Particular days of the week may have been dedicated to the death deities and possibly a whole month of festivities, as was the case for Aztec Mictecacihuatl who presided over roughly a month of commemoration of dead ancestors until the Spanish colonial church collapsed it into the first two days of November.

Very few representations remain due to the iconoclastic activities of the Spanish clergy however a few remains excavated by Roberto Gallegos in Zaachila reveal that Pitao Pezeelao was represented with a skull for a head with a human body in a plaster frieze, and as a skull with a skeleton body in a tomb, wielding a sacrificial knife in his right hand. From decor in ceremonial sites we also note that these death deities were associated with owls. No full representations of Xonaxi Quecuya perdure, but records relate that she not only cured the ailing, but also came to collect the spirits of the deceased.

Devotion to death deities and all other Indigenous sacred figures was outlawed by the Catholic Church and veneration of Christian figures imposed. The Spanish brought many effigies, including la Parca (Grim Reapress) as a representation of death, to enforce and champion the Catholic creed. Nevertheless these representations were not simply assimilated, rather they were re-mapped according to Indigenous chorography. The Bën zaa transcribed local spiritual forces into the Christian world of Saints. The Catholic churches had replaced the pre-Hispanic temples yet not eradicated their deities, for when Zapotec people would pray to the statues of saints within them, they transfigured them into pre-Hispanic deities. Colonial records reveal that the Zapotec, much like West Africans in Haiti, began consciously syncretising their autochthonous deities with Catholic Saints. For example, one record notes that Bën zaa men, before going on a hunt, would go to the church and place candles before the image of Christ as they prayed not to Jesus, but to their god Nosana, a deity associated with creation, deer and fish, for a successful outcome.

It is not a large leap to imagine that images of La Parca, the Grim Reapress as Andrew Chesnut has called her, the Spanish representation of death depicted as a woman by the Iberians, may well have been conceived of and venerated as Xonaxi Quecuya. The skeletal remains, or relics, of Catholic saints were oft paraded around by the Church during festivities and once again these may have been associated with Indigenous death deities. Nevertheless, no accounts can confirm this and with worship of Zapotec goddesses and gods punishable by incarceration, torture and death it is little wonder that nothing is heard of the veneration of death which was driven underground until the 1940s when Santa Muerte surfaces in anthropological accounts. And one of the first places she appears in, is Oaxaca.

Santa Muerte:

We have scant knowledge of the veneration of death from the 16th century until the 20th century but Santa Muerte who egresses from the umbra, as described above, in the 1940s, must be understood as a syncretic reconfiguration of the devotion of death and its recrudescence in the post-colony. Santa Muerte is a Mexican folk saint who symbolises death. She amalgamates, what some understand as Aztec, but I argue herein, also Zapotec sacred beliefs and praxis. She is typically depicted as a female Grim Reaper, wielding a scythe in her right hand, just as La Parca did, and just as Pitao Pezeelao brandished a knife in his right hand. In her iconography she usually dons a long cloak that covers her from head to toe. The colour of the cloak has deep symbolism and usually corresponds to the favours desired by the devotee. Just as Xonaxi Quecuya and Pitao Pezeelao were, Santa Muerte is often accompanied by a tecolote, an owl. This nocturnal bird in Indigenous mythology is associated with death for it is said that ‘when the owl screeches, the Indian dies’. During my research in Oaxaca, I was frequently told that if one saw an owl outside one’s house it was a sign that death would soon come to one within.

In accord with her persona as a fierce female folk saint operating primarily on behalf of female devotees, Santa Muerte was first discovered by American anthropologists in the 1940s who came across her being petitioned for matters of love magic in the Costa Chica region of Oaxaca, among other places in Mexico. Indeed from the 1940s to the late 1980s, the American and Mexican ethnographers who encountered her across the Mexican Republic reported the saint of death serving a sole purpose – as a love sorceress for aggrieved Mexican women who believed their husbands or boyfriends were cheating on them. Women devotees congregating in clandestine make-shift worship spaces would recite the oldest known prayer to Saint Death, which is printed on thousands of her votive candles available across the entire continent of America. This prayer asks the Skeleton Saint to swing her sharp scythe to remove the other woman from his path. Once the paramour is spiritually neutralised, Santa Muerte’s harvesting blade impels the errant husband to return to his wife, humbled at her feet, asking for forgiveness and promising not to stray again, under threat of his own spiritual destruction. Since the late 1980s Santa Muerte has expanded her repertoire to become a multipurpose miracle-worker, but matters of love, health, and wealth, particularly as they relate to subaltern female devotees remain paramount and her curative powers attest to her ancient origins for Xonaxi Quecuya was once turned to for her salubrious sacred skills. However, as a death deity, she is also turned to for vengeance by women, to punish those who have harmed them and their families.

In a state where they have few options, the fierce female folk saint of death has become the primary spiritual ‘weapon of the weak’ for women marginalised by cultures of patriarchy and victimised by the current epidemic of femicide. The redux of the female worship of death by women in Mexico also correlates to the revival across the globe of goddess-based traditions, whether Wicca or New Age, women across the world are moving away from phallocentric faith that disempowers them, towards conceptions of the divine feminine that reflect their realities on the ground and armour them with the agency and attributes they need to survive in a world that remains hostile to the female gender.

Meeting Death:

My first encounter with Santa Muerte was on a sultry tropical evening in the middle of February in 2017. Frondescent palm leaves, nigricant in the night, melted into an amorphous mass. Stars began to besprinkle the sky, the moon slicing the blackness with a silent orb as people became shadows. Riding in a van with the windows wide open, the warm air fanned me and then overwhelmed me with its pungency, for it was also that time of night when people begin burning their rubbish. Smokey fumes merged with jungle petrichor making the darkness even more opaque.

Having read the work of Andrew Chesnut on Santa Muerte veneration I was intrigued. I was determined to find a shrine dedicated to the Bony Lady, one of her many monikers, thus I had enlisted a local guide to aid me. Although he did not know where her shrine was located, Raul promised to help me navigate the obscure roads of rural Oaxaca. We had searched earlier on in the day but to no avail. I had been told that a temple existed on the outskirts of a local town but asking around it was proving impossible to reconnoitre, especially since many locals associated Santa Muerte with Satan, recalling the colonial chorography of non-Christian conceptions of the divine and did not want to direct us. I noticed how my guide would whisper her name in hushed tones when asking locals to indicate directions. It was not until night fell that the Saint suddenly surfaced.

‘Stop!’ I yelled as a scythe severed my view. There she was. A small altar consisting of a basic building with three concrete walls and then bars at the front that let one’s eye alight upon the Skeleton Saint standing beyond. The shrine stood illuminated by the side of the road, replete with flowers, votives, gifts of mezcal, Coca-Cola and candy for the Skeleton Saint. I disembarked from the van absorbed in the cynosure of Santa Muerte depicted in the first statue as a bride in a translucent gown with a wolf’s head adorning her cranium. Another effigy drew me in as I turned to the right, her skeletal form in a feather headdress with Pre-Columbian themes, and yet another statue to the right revealed her bony body dressed in a blue gown. Images and items adorned every inch of the space. The ceiling was painted with a stars and planets motif that recalled the pre-Hispanic obsession with the movements of astronomical bodies to calculate the holy calendar. Numerous owls and skulls surrounded the Saint, richly reminiscent of pre-Hispanic iconography. Although these items were made of plastic and porcelain, possibly in a Chinese factory, they still spoke to me of the past, of continuity, of the longue durée.

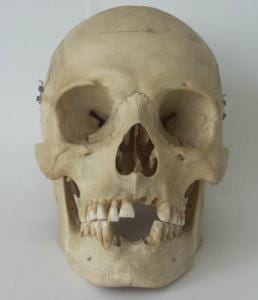

Skull at Santa Muerte shrine, 2017

Skull at Santa Muerte shrine, 2017

Only two days ago, I had driven several hours southward to the archaeological site of Copalita. Amidst the impressive collection of items dating back to 500 BCE, discovered during digs, my eye had been attracted to one particular item: a human skull caringly coated with multi-coloured mosaic and whose eye sockets had been filled in with white stone in an act of devotion. The cranium had been used by the Indigenous peoples who had lived here 2500 years ago in veneration of the dead. As I stood staring at the glaring gaze of the Skeleton Saint and the skulls around her, a small but sturdy woman emerged from the darkness beyond the shrine. This was the first time I met the owner of the altar, who even then struck me as an unbelievably strong and determined person.

Skull found at Copalita, 500 BCE

Skull found at Copalita, 500 BCE

Senora Lucia recounted that one evening twelve years ago, lying on what she thought was her death bed, she lay suffering. She had lost blood, was suffering from jaundice and could no longer move, she had fallen ill many years ago and every day had worsened until all she could do was rest supine and wait for death to come. And death did come, but not as she had expected. One night, an owl shattered the silence of her room as it fluttered toward her face. Astride the owl sat la Santa Muerte, cloak floating around her, eyes burning red. She spoke in gravelly tones to Senora Lucia and with her great powers, cured her. The next day Senora Lucia awoke fully recovered. As she had vowed to, in a quid pro quo, Senora Lucia erected a small shrine to La Santa. That was twelve years ago and every year that shrine grew until it was the independent edifice that stood proudly now, its own separate structure by the side of her simple dwelling. Senora Lucia lavished it with attention as did the devotees who visited. I had to leave Oaxaca a few days later but determined to come back I arranged to return in 2018.

When I came back to the same spot, the following year, it was no longer. It had been demolished and in its place a chapel twice as large had been built. Although Senora Lucia’s house was a very modest dwelling, the shrine freshly built, was a strong concrete structure with large panes of glass at the front and in the back cross-shaped glazing adorned the structure. Four statues now bedecked the fane: sitting at the centre, Santa Muerte sat on a throne painted in the seven colours of her seven powers (siete potencias). Around her the three skeletal figures from last year, although the Santa Muerte who had once been attired in a blue tunic was now dressed in a silver gown and a golden cloak. Not only was I overwhelmed by the size of the chapel in comparison to its previous scale but the small pot-holed road on which it was previously situated was now far larger: an almost finished two-lane highway. The temple was overflowing with vases of red, yellow, white and pink flowers, gifts of cigars and cigarettes lay in the Saint’s outstretched hands, at her feet offerings of alcohol, soda, water and food. At least eighty votives twinkled, their flames darting like luminescent lizard tongues in the evening zephyr.

‘More people come now than ever due to the road. Viene de todos’ (all kinds of people come) but, above all, it is women who come’ Senora Lucia told me when we met for the second time. She remembered who I was, how could she forget the only gringa who had ever come to her chapel. Gringa is slang for white North Americans and Europeans. ‘Why more women?’ I asked her.

Mighty Mexican Mother:

The answer to this question, ‘why so many female devotees?’ varied depending on Senora Lucia’s mood: pensive or spiritual. I could not help but ask several times and ask other female devotees too, especially after seeing for myself, women come diurnally and vespertinally to kneel before the Saint and offer her prayers, flowers, tears of joy or of sadness.

‘More women come because we have more problems than men, they may not even be in our lives any more’ Senora Lucia sighed. ‘Because no matter what happens the children still must be fed, the tortillas must still be made, the leaves must still be swept. Es una lucha’ (it is a battle). ‘She listens’, Senora Lucia told me. ‘No else may do but she does. La mujer may be worth little to most here, but not to la Santa. She respects us, as we respect her. She is strong and powerful and takes care of us.’ She watches over them, because no one else does.

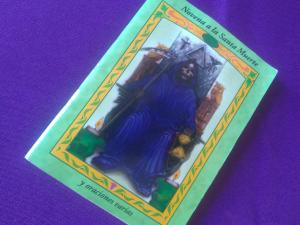

Prayer book gifted

And in the prayer book that Señora Lucia handed to me, which I am not sure she can read, the oraciones evince the potency of, and deference that there is for this fierce folk saint , she is ‘Gloriosa y poderosa Muerte’ (Glorious and powerful death), ‘Señora Invencible’ (Invincible Woman) and ‘Milagrosa y Majestuosa Muerte’ (Miraculous and Majestic Death). And I know a woman’s day is never over here and that women must have unassailable strength. They seem majestic and miraculous to me, dignified, powerful and stoic as I watch them haul heavy bags of rice up long, winding roads; patiently feed their children; swiftly sweep the leaves from outside their homes and they are brave. Their ability to deal with anything seems far superior to my own.

I wake up to an ominous drone, when overnight a swarm of hornets invade my house, making a nest in the eves above my bed and almost run out of bed. As soon as I see Senora Xiadani I tell her about the unwelcome guests. Without fear she enters my bedroom and rapidly exterminates them all, as they fly around bellicose and buzzing, with nothing but a feather duster, fly spray and a large dose of aplomb. Hornets are the least of her problems. It is always necessary, Senora Xiadani tells me as she deftly and determinedly kneads cornflour into a plantain leaf to make the outside of the tamales she is instructing me how to cook to: ‘protect daughters from the narcos that steal girls to sell them into prostitution; to protect your family from the narcos whom you should never get involved with as if they think you have crossed them somehow they will kill you all; to keep your children well away from the men that snatch them to sell their organs’.

I also hear from many women about the husbands who drink too much and that don’t take care of their families, or that don’t let their wives talk to anyone but them and their children, and then beat them if they do. I am told by women about the men who promise to marry them but leave them pregnant and with no money. Then there are those spoken of in hushed tones, who prey on local women, raping and killing them. Some Indigenous women if victims of a minor crime would rather not report it, for if the police come, I am told, the women may experience a worse crime. It is not unheard of even for those who supposedly uphold the law, police officers, to rape Indigenous women and girls. No one cares about them. They have no recourse to justice. Violence against women and femicide rates are high in this region. And in that prayer book, given to me by Senora Lucia, I notice how the prayers are all written for women to recite, with verbs always translated according to the feminine form because she if they ask, if they pray, they tell me, she will watch over them.

In the face of these and many more problems, as Senora Lucia explained, the children must still be nourished, food must still be paid for and life must go on despite it all. And if the Virgin Mary, meek and mild, is absent from Senora Lucia’s shrine and instead the ferocious female face of death looms larger than life, I cannot help but think that it is because meekness, mildness, submission can no longer sustain these women, who every day fight for their children, for their lives, for another square meal and for whom death is ever close. She watches over them and if their time should come then they know her face well, they are ready for her. And this she, this Skeleton Saint, who reflects them, is battle-hardened like they are and is ready for la lucha. If as Virgil said, man makes god in his own image, does not woman make goddess in hers?

When I ask about Santa Muerte’s origins, I am told that she is an eternal mother, older than Mother Mary, as Anayeli explains to me, ‘since the time before the Spanish came, when we lived alongside the Maya to the South and the Mexica to the North, she was collecting souls, and wandering our world. She has always been with us’. Santa Muerte is understood as a mother who comes from a past before the Spanish, a past that is Indigenous and precious.

Yet, despite the pope’s condemnation of the Skeleton Saint as heretic and non-Catholic and despite Zapotec women conceiving of her as originating from a pre-Hispanic age, even if other locals condemn the practice as satanic, devotees still conceive of themselves as Catholic. I note this when another night I am told ‘More women come because we are more spiritual, we are closer to God and closer to la Santa’. And that same night I tell Senora Lucia that I want to write a book about her, about all the women I have met, and about La Santa, because their story needs to be told, but I need funding from the government or another body so that I may come back and spend more time studying. And Senora Lucia, her silver-hair reflecting the fairy lights that she has adorned her Skeleton Saint statues with, suggests that we ask for funding in prayer and of course, as an anthropologist whose middle name is participant-observation, I could not be more enthusiastic about this.

Senora Lucia surprises me as she starts the ritual with the Lord’s Prayer, and as we kneel, hands clasped in prayer, we first appeal to ‘Padre nuestro que estas en el cielo’ (Our father who art in heaven). But abruptly we deviate, she implores Santa Muerte for her blessings, as together we light incense and a gold-coloured votive, appropriate for such occasions. Senora Lucia tells me that I should come back, how every month, she holds a large rosary where dozens of women come from all around to venerate la Santa together. And I recall how the first ever shrine to Santa Muerte, ever publicly erected in Mexico City and written extensively about by Andrew Chesnut, was started by a woman, Doña Queta (aka Enriqueta Romero) and that it too has served to unite and empower female devotees.

Weapon of Women:

I realised that night, that I am but one of millions of women, who in Oaxaca, Mexico, South America, North America, indeed the world, has supplicated the Skeleton Saint in prayer, offering her a votive, or perhaps a coconut, or a bottle of water or a can of beer, for something that seems vital yet ungraspable. Yet my concerns are paltry compared to Bën zaa women’s. The many coloured candles always flickering day and night, placed by female devotees at the shrine reveal their prayers, their lives, their stories. They plead Santa Muerte for money, lighting the yellow and gold candle ‘dinero ven a mi’ (money come to me) as they struggle to feed their families and themselves, often as single mothers with nothing but a meagre income. Lighting the white votive of peace, they ask for protection for their children, for themselves,and safety for their household as they sleep at night, requesting the Saint’s supernatural aegis to guard them from the inimical, iniquitous figures that lurk around them- narcos, organs traffickers, rateros (robbers), criminals and recidivists.

They ask for an end to violence from fathers, husbands, and others who physically and sexually assault them as they light ‘cordero manso’ the votive of the meek lamb that is said to render a dangerous man docile. They propitiate for love, as they place the red votive, often with crimson carnations or roses before the Saint. For a husband will be able to protect them in a society where as single women they are vulnerable and aid them to afford food to put on the table. They also ask for revenge, as they light the black candle whispering imprecations against those who have assaulted and harmed them as only she watches over them. In a state without justice where impunity abounds for gendered violence, especially against Indigenous women, the Skeleton Saint, who iconographically is often depicted as holding the scales of justice, is the only one they can turn to.

Conclusion:

If the empowerment of subaltern, especially Indigenous, female devotees, took place only in the spiritual realm it might be tempting to dismiss devotion to Santa Muerte as an ‘opium of the masses’ that pacifies marginalised women who might otherwise rise up against their oppression and socioeconomic exclusion. However, as has been alluded to in the cases of Senora Lucia and Doña Queta, the Mexico City godmother of the cult, what is now the fastest growing new religious movement in not only Mexico but also across the Americas is largely led by women. In addition to Doña Queta, Enriqueta Vargas was at the vanguard of organizing and institutionalizing devotion to death as the charismatic head of Santa Muerte Internacional, based on the gritty outskirts of Mexico City. Until her untimely death, last December, she was able to unite major shrines and temples across Mexico, the U.S., Colombia, and Costa Rica under her command.

Thus in great contrast to Catholicism and most Protestant denominations in Mexico which restrict the clergy to men, devotion to Santa Muerte empowers women as religious entrepreneurs, some on a larger scale and others such as Senora Lucia on a much smaller one. As is the case in African diasporic religions, such as Brazilian Candomblé, female Santa Muerte devotees as proprietors of public shrines can significantly supplement their income through donations, securing paid sponsors, and by selling devotional paraphernalia, such as votive candles and statuettes. Some of the more successful shrine and temple owners are even able to quit their day jobs and dedicate themselves full time to their devotional activities. Doña Queta, for example, stopped selling quesadillas to her neighbors in the notorious Mexico City barrio of Tepito years ago. Furthermore, their social status in the community may be significantly altered. Senora Lucia, although a single, unemployed mother of many children is accorded deference from the many devotees who come daily and nightly to the shrine which she keeps immaculately clean. Many, turn to her to lead prayer, or advise on spiritual matters and she is the recipient of constant cash donations for her sacred work.

Activities such as the monthly rosaries also create female spaces of devotion where women empower one another, extolling advice, warning each other of dangers and hazardous characters at large in their communities. Moreover, as a fierce and feisty Saint, Santa Muerte veneration imbues female devotees with strength and vindicates their desires for justice, for affluence and for a better life, rather than enforcing ascetic humility. For Indigenous women, as I saw amongst the Zapotec women of Oaxaca, who have few means nor opportunities and who deal not only with financial difficulties but physical hardships that range from poverty, sickness to gendered violence, a strong community of women devotees with a powerful female folk saint at its fulcrum whose origins speak to a pre-Hispanic past while allowing them to navigate the difficulties of the post-colony, legitimises their identity both as women and as Indigenous. In short, as a weapon of the weak, or perhaps more accurately a weapon of women, devotion to Santa Muerte empowers subaltern and Indigenous Mexican women socially, spiritually and financially.

*Dr. Kate Kingsbury obtained her doctorate in anthropology at the University of Oxford, where she also did her Mphil. Dr. Kingsbury is a polyglot fluent in English, French, Spanish. She is a polymath interested in exploring the intersections between anthropology, religious studies, philosophy, sociology and critical theory. Dr. Kingsbury is Adjunct Professor at the University of Alberta, Canada. She is fascinated by religious phenomena, not only in terms of their continuity across the Holocene and into the Anthropocene but equally interested in the changes wrought to praxis and belief by humans ensuring the infinite esemplasticity that is inherent to all religions, allowing for their inception, survival, alteration, regeneration and expansion across time and space. Dr. Kingsbury is a staunch believer in equal rights and the power of education to ameliorate global disparities. She also works pro bono for a non profit organisation that aims to empower and educate girls in Uganda. Follow Dr. Kingsbury on Twitter