Co-authored by Dr. Kate Kingsbury* and Professor R. Andrew Chesnut

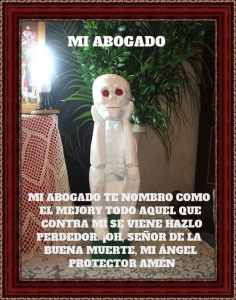

Having spent the past decade researching a Mexican folk saint whose name translates as both Holy Death and Saint Death, we have been compelled to grapple with the significance of the near universal desire for euthanasia whose original meaning derives from Greek. ‘Eu’ means ‘good’ and ‘thanatos’ means ‘death’, put together the term means ‘good death’. Euthanasia is thus defined as fast and peaceful death preventing further sufferings. One of the main appeals of the three Latin American folk saints of death, Santa Muerte, San la Muerte, and Rey Pascual is their reputation for granting devotees and their loved ones a relatively peaceful end of life. In a Mexico and Guatemala plagued by interminable drug wars and the Covid-19 epidemic there is no shortage of bad death in which lives are snuffed out prematurely and painfully by violence and more recently, virus. Of course devotees first beseech the death saints for protection and healing from such scourges, but in the event that their petitions fall on deaf bony ears believers can turn to Our Lord of the Good Death, one of the monikers for Argentine San la Muerte, and ask him or his fellow skeleton saints for euthanasia.

If the desire for a good death is so central to the mission of the skeleton saints that two of them bear it in their names, Holy Death, it’s also because the wish to die peacefully has been an important aspect of Christian, especially Catholic, belief and practice. The original holy death, of course, was Christ’s on the cross, which while anything but a peaceful end made possible the hope of eternal life for His followers. So significant was the idea of the holy death of Jesus that there are Iberian Catholic advocations of both Christ and Mary called Christ of the Good Death (Cristo de la Buena Muerte in Spanish) and Our Lady of the Good Death (Nossa Senhora da Boa Morte in Portuguese). Catholic brotherhoods in Spain and Portugal, and later in several Latin American nations, formed on the axis of these mortal manifestations of Jesus and Mary. Spanish confraternities -such as Cofradía de Penitencia de la Buena Muerte in Cadiz- would carry their exquisitely carved effigies of the Virgin and Christ of the Good Death on Good Friday as part of the famous Holy Week processions of southern Spain.

For Iberian and Latin American Catholics holy death wasn’t only about Christ’s monumental sacrifice on the cross but also about their own good death and that of their loved ones. This could only be guaranteed through piety and a life devoid of sin, as a good death also meant avoiding the fiery pits of hell and being granted entry through the pearly gates. Daily prayer, following the ten commandments, and confessing often –especially upon one’s death bed– would entail transgressions were forgiven. The good Christian must be prepared for the Last Judgment.

Ubiquitous memento mori imagery, especially skulls and skeletons, in Catholic Europe served as reminders to believers of their inevitable death, exhorting them to lead a Christian life free of mundane vanities which could only distract from the hope of eternal life in heaven. Indeed Vanitas paintings, pioneered by Dutch artists, are filled with skulls, withering flowers, and rotting fruit as lessons in the fleetingness of temporal pleasures. Poets also referred to man as a bubble in the maxim “homo bulla est”. This was popularised by Erasmus, the Dutch Catholic theologian and became a leitmotif in Christian paintings. Homo bulla est, just like the withering flowers of memento mori, served to remind Europeans of the brevity of life and arbitrary nature of death; humans might believe they are substantial, but like the ephemeral bubble that disappears with one prick, life is extinguished in the blink of an eye, often with no warning before our powerless hands.

Memento mori reminded Christians to stay on the straight and narrow, adopting the precepts extolled, such as prayer and a sin-free life, Catholics could then aspire to a good death in which their lives ended peacefully surrounded by loved ones and with Last Rites administered by a priest, allowing the dead to access heaven directly. However, just as the Black Death made euthanasia impossible for millions of Europeans seven centuries ago, Covid-19 is now denying a good death to hundreds of thousands across the globe who may die suddenly, alone and with little to ease their suffering. No wonder the fastest growing new religious movement in the West is centered on Holy Death (Santa Muerte).

Prayer remains an essential coping strategy during times of Coronavirus, whether for faith healing or for preventing contagion. While many churches may be closed across the world, people continue to ask for divine intervention to avoid a bad death from Covid-19. In Mexico, many Santa Muerte temples remain open, such as that of Yuri Mendez in Cancun. Her latest rosary on the 2nd September 2021 focused on healing of Coronavirus, many prayers were offered to the folk saint of death that she might not only prevent sickness, cure the ailing but also end the pandemic and thereby end suffering and mala muerte (bad death) from the virus. Yuri Mendez’s shrine features many effigies of the folk saint of death, but her most beloved named Yuritzia was especially dressed for the occasion. Dressed as a frontline nurse in white and blue but with the lacey headdress often seen in Spanish depictions of the Virgin Mary the folk saint syncretically meshed secular and sacred methods of healing. Attendees chanted in unison as Yuri led them into prayer, “Santa Muerte save us and the entire world.” Santa Muerte, as the most recent manifestation of a good and holy death, continues to remind us of our fragility and the brevity of life on this earth.

*Dr. Kate Kingsbury earned her doctorate in anthropology at the University of Oxford and is author of numerous articles and book chapters on Santa Muerte and African Diasporan religion. She is writing the forthcoming “Daughters of Death: The Female Followers of Santa Muerte” for Oxford University Press. Dr. Kingsbury is a Research Associate of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia, Canada. Dr. Kingsbury is a staunch believer in equal rights and the power of education to ameliorate global disparities. She also works pro bono for a non profit organisation that aims to empower and educate girls in Uganda.