by Nathan Roberts

by Nathan Roberts

When I saw the film Selma for a second time, I sat next to my friend Chloe. As the credits rolled, she turned to me and remarked: “You know, honestly, I can see why DuVernay wasn’t nominated for the Best Director Oscar.”

“Hmm…” I said.

In the lobby, she elaborated: “I just think Twelve Years A Slave is a better film in this genre, if we can call it a genre.”

“But… isn’t the acting good, at least?”

Ava DuVernay, Selma’s director, is notably black and female––a double minority in her masculine, whitewashed industry. My friend Chloe is a black, female filmmaker, too. And so perhaps I unconsciously expected, as we walked out of this fine film about racial equality––a film that nudges America ever-closer to racial and gender equality by merely existing––to hear some sort of quiet, satisfied sigh, or a frustrated jab at those sexist Oscar voters, or maybe even cries of pure enthusiasm. (We’re New Yorkers, though. I knew that last option was a long shot.) What I did not expect was the idiosyncratic, contrarian opinion of an intelligent artist. And Chloe is certainly an idiosyncratic, intelligent artist. By assuming more positivity from her, I actually expected less of her.

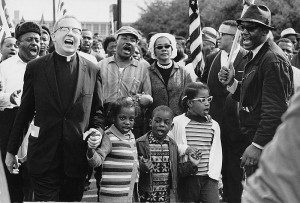

Was it not Martin Luther King Jr. who warned against this sort of poisonous generalization, against this type of a priori assumption? What’s that famous line, the one I heard in elementary school every January? “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” The content of their character. The dream of Martin Luther King Jr. was not merely the dream of non-discrimination. It was certainly not the dream of homogenous “equality,” either. It was a dream predicated on defending internal particularities and supporting unique personal characteristics. I don’t think it’s a stretch to suppose that if King were to hear Chloe’s voice of dissent, he would approve.

However, I’m still slowly, steadily learning (along with the American Church, it seems) how individual particularities are shaped by cultural and ethnic traditions. Even though I grew up in a fairly diverse city, this is all a little new for me. Only at NYU, with the help of InterVarsity Multi-Ethnic Christian Fellowship, have I begun to discover the peculiar joy that can arise when a community speaks openly and inclusively about ethnicity and culture. Only though InterVarsity have I found a pleasing alternative to the old “American Melting Pot” analogy: the “American Salad Bowl,” in which differences aren’t melted and deformed into indistinct sameness, but maintained for the mutual benefit of all people “mixed in.” The salad bowl contains a harmonious celebration of particularity.

And yet, the notion of “colorblindness” still sifts through the American cultural fabric. It still sifts through me. It wants to pretend as if cultural characteristics ought to be ignored rather than cherished. It wants to turn “#blacklivesmatter” into “#alllivesmater,” as if the second statement somehow fixes the first. It’s wants us to think about “Jesus not color,” as if Jesus were somehow colorless or cultureless. It wants us to forget the fact that one day, when the glory comes, there will be a “great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and before the Lamb.”

Morgan Freeman wishes we were colorblind, or so he once said. On 60 Minutes he was asked: “How are we going to get rid of racism?” His now-famous answer: “Stop talking about it. I’m going to stop calling you a white man and I’m going to ask you to stop calling me a black man.”

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences decided to take Freeman’s attitude out for a spin this year. Well, mostly. As he walked on the Oscar stage, Neil Patrick Harris opened with a quick quip: “Tonight we honor Hollywood’s best and whitest––sorry, brightest.” The joke was enough to acknowledge public frustration with 2014’s overwhelmingly white Oscar nominees (the least diverse bunch since 1998) and nod to Selma’s near-shutout, but it didn’t even pretend to be self-deprecating. Nor did it express sincere disappointment. Harris nodded at the elephant in the auditorium for a quick chuckle before singing on his merry way. The Dolby Theater seemed to collectively sigh: At least we got THAT out of the way.

And then the Academy went on to try, as hard as it could, to prove that race wasn’t an issue worth talking about. Out came (by pure coincidence, surely) a seemingly endless parade of black presenters––Oprah Winfrey, Kerry Washington, Terrence Howard, Dwayne Johnson, Eddie Murphy, Octavia Spencer, even Kevin Hart, for goodness sakes––in order to mitigate our collective frustration. Spencer, Oscar-winner from The Help, spent the entire evening “helping” Neil Patrick Harris with what turned out to be a particularly dull gag. Let’s not even talk about how Harris tried to rope David Oyelowo into the proceedings.

While I wish that every Oscar ceremony would feature diverse presenters, this exception-to-the-rule reeked with the scent of lead-footed PR. Journalist Rembert Brown snarkily tweeted, as if he were the academy: “‘If we sit Kevin Hart close enough, it will TOTALLY make up for the Selma thing.’” Even snarkier:“The Oscars have more black friends than me.”

One of night’s best moments, Common and John Legend’s downright holy rendition of Selma’s “Glory,” was even tainted by unacknowledged tension. Some (well-meaning, I’m sure) production designers erected a large replica of Selma’s Edmunt Pettus Bridge, site of the famous standoff between King’s marchers and the Selma police force. Common emerged through the faux-bridge, MLK-style, accompanied by a choir of black marchers. As Wesley Morris describes the proceedings:

“By the time the number had concluded, the choir’s sea of black faces stood at the edge of the stage and spilled down the stairs at the foot of the predominantly white house, where the audience had risen to applaud, some through tears. Hollywood does have a race problem, and this image seemed to sum it up. This getting on one’s feet and clapping constituted an ovation, certainly. But from some angles, it was impossible not to see the moment for what it also was: part of a ceaseless standoff.”

Do you think Freeman’s strategy, the don’t-talk-about-race-and-the-problems-will-go-away strategy, worked? Or did merely lend the evening’s proceedings an undercurrent of guilt and embarrassment? Does this strategy admit our national need for cross-cultural growth, or does it encourage the sort of naïve repression that lead to post-Ferguson outcries?

It’s admittedly easy to point fingers at the Academy, as if it were some sort of looming, singular deity, instead of a decentralized group of industry workers. But 2015’s Oscar nominations do seem to exemplify where we are, fifty years out from the King’s march from Selma, and how we ought to proceed.

For as well meaning as the Academy’s “diverse presenter” gesture may have been, the implied sentiment seems a little beyond the point. It would be unkind, and patently untrue, to assume that Academy voters don’t want to include black people because they are Capital-R Racists. I know some of them––they’re not. Cheryl Boone Isaacs, the Academy President, is a black woman, after all.

2014’s whitewashed nominees weren’t products of the sort of bigotry King fought in Selma. Rather, the snubbed contenders were casualties of a group’s reluctance to reach outside of its comfort zone. This hesitancy led to a near-shutout for the critically acclaimed Hollywood outsider Boyhood, too. Every year, it leads to a pitifully small number of foreign film inclusions. For the past several years, this attitude has lead song-and-dance men to serenade movie star crowds about––what else?––how great movies are. 2014’s Best Picture winner, Birdman, was the third Best Picture winner in five years to focus on the Film Industry: its issues, its ambitions, its self-absorption, and, ultimately, its glories.

Dr. King’s namesake, Martin Luther, had a word for this sort of ceaseless self-reference: incurvatus in se, which can be roughly translated as: “curved inward on oneself.” When we curve in on ourselves, on our industries, our families, our clans, we don’t necessarily hate others––we’re just too self-obsessed and group-obsessed to care about their own stories. We’re like Jesus’s rich man in Hell: we don’t necessarily hate others; we just want them to help us, and our families, out.

On one hand, self-absorption and group-absorption isn’t as actively aggressive as Capital-H Hate or Capital-R Racism. But, on the other hand, passive narcissism obscures the damage it inflicts on individuals and communities who long to be heard. Instead of addressing systemic injustice, it congratulates itself for its own “open-mindedness.” It parades its “black friends” on a stage for the sake of PR instead of deeply caring for the content of their individual characteristics.

The Oscars can teach us that it’s not enough to merely assume that the “race problem” is over, or to insist on some sort of lackluster “colorblindness.” But the Academy’s failure to honor diverse stories should encourage us to engage with the diverse stories that surround us. We should strive to take joy in the individual characteristics, the idiosyncratic particularities, of all the people in our lives.

Not that this will be easy. “Selma is now for every man, woman, and child.” This is one of the best lines from “Glory.” But what does that line mean, exactly? That the strides taken in Selma, Alabama affect us all, everyday? Perhaps. That would be certainly true. But I sense an imperative in this line, the same imperative that runs through this entire song––an insistence that the spirit of Selma be now. The insistence that we fight, day in and day out, for what Dr. King called “a kind of dangerous unselfishness.” And it will be dangerous. Anyone who has engaged ever engaged in serious multi-ethnic dialogue can tell you that it’s a constant fight––a fight to remain receptive, a fight to truly listen, a fight to apologize when you presume, stereotype, or offend. (My The High Calling colleague, Deidra Riggs, has written about these challenges with grace, wit, and wisdom.)

And yet, if Church were to take King’s charge seriously, perhaps it would be, as he dreamed, “not merely a thermometer that record[s] the ideas and principles of popular opinion, [but a] thermostat t[hat] transforms the mores of society.”

One day.

Editor’s Note: Another great article by former The High Calling summer intern, Nathan Roberts.

Image from Wikimedia Commons.