The best teaching involves the whole person: their beliefs and views, their reasoning and arguments, their hopes and fears. For this reason, I propose that we re-frame our debate about teaching from a faith-based context. It is not a fundamental feature of faith that it must posit itself as the only point of view. Faith, as St. Anselm so pointedly reminds us, seeks understanding.

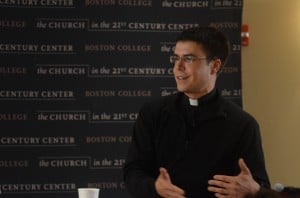

I often encounter the misconception that a church’s main role is to separate the world into the sacred and the profane: us and them. People are surprised to hear that as a Jesuit-priest-in-training I work at a University. Christians remark, “isn’t academics so terribly secular? How can you compartmentalize who you are?” And non-Christians react with suspicion, watching to see if I am sneaking a secret agenda into the material. However, the reality is that freedom is at the very core of Christian thinking and I flourish in an environment that encourages freedom of thought.

I teach philosophy, mostly first-years. And one of my main tasks is to change the mentality of the students that I am pouring the water of knowledge into their waiting, sponge-like minds. A professor holds many things to be true: but it is anathema to the professor for students to decide that things are true simply because the smart professor has said so.

I try to help students develop tools for thinking. Tools for investigation, for argument, or for weighing and making decisions. I tell the students it is their job to seek out what is true. I often challenge both Christian and non-Christian students with arguments that show apparent inconsistencies in their beliefs. There are reasonable arguments against some Christian ideas; it is my hope that students when students learn to engage with these arguments and think them through, their faith becomes stronger. At the same time, I hope by challenging non-Christians with their beliefs they will construct a deeper and better thought-out worldview. In both cases, the result of being challenged in one’s beliefs is to learn and grow.

My academic obligations and my obligations as a believer are not fundamentally opposed. The prize of academics is to love and to seek the truth using the best tools and methods available. And a good Christian will affirm that a sincere and free search for truth will lead to God – though perhaps in ways that are not immediately apparent. A tried and true Jesuit motto is “to find God in all things.” There is no need for me to shoehorn God into the disciplines of history, literature, science, business, medicine, etc. For me, God is already present and active in these human stories, moving hearts and minds to greater knowledge, greater liberation, and ultimately a greater love.

Self-knowledge is vital. A person in dialogue, in the context of a shared love of truth, must be honest about one’s foundational assumptions and beliefs. But these beliefs become jumping-off points for dialogue: discussion-openers rather than discussion-closers.

There are points of fundamental disagreement between those who have a faith perspective and those who do not. But if both persons seek the truth with sincerity, they will not find themselves engaged in two separate labours. In fact, they may be of greater assistance to one another: we learn much more from those who challenge us.

And so neither do I compartmentalize, nor do I subvert the material to my own agenda. I simply provide the best truth-finding tools that I can and encourage my students to seek out their answers, perhaps with fear and trembling; but always with an openness to learning from the experience of others rather than by dividing the world into us and them.