Ever since Vatican II we as a church have been unpacking what it means to have a preferential option for the poor and vulnerable. How might this option apply to people in the LGBTQ community?

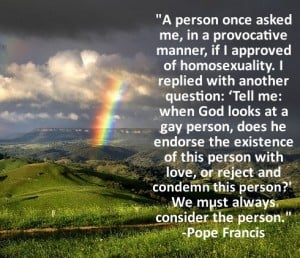

Pope Francis has made comments in recent years that indicate a loving, pastoral approach to LGBTQ persons in the church and in the world. God loves and approves of the human person without condition or exception. There are several factors that hinder this loving response and several elements of church teaching that might help it. And help we must: many of God’s children are suffering, rejected, and de-humanized. Pope Francis’ comments deepen our desire to love and care for people, many of whom have been deeply hurt and marginalized. How can we respond thoughtfully and compassionately to the cries for help around us?

Many Catholics are not knowledgeable about the struggles faced by LGBTQ persons. They may also be unaware of the church’s teachings on this topic. This lack of knowledge makes us tentative, fearful both of stepping outside the bounds of church teaching and also of giving offence in a sensitive context. Rather than address individual other people, we retreat to generalities, criticizing society in general for permissiveness and excess. These criticisms can hamper genuine dialogue with our actual neighbours, the people we meet. In order to step forward towards being affected and moved be a face-to-face recognition of other people, we need greater knowledge.

The first kind of knowledge we as a church can seek is that which comes from friendship with marginalized people. LGBTQ persons are waiting to hear that we as a church are interested in making our parishes, schools, and homes safe space: where each person’s dignity is upheld as sacred.

Jesus created this space around himself wherever he went. How many times does Jesus stand face-to-face with those who are excluded from society? And even during times of prayer and solitude, he allows himself to be interrupted and surprised by encounters with others. He allows himself to be moved with compassion.

A friend and colleague of mine, a priest who has been a friend to LGBTQ persons in a parish context for two decades, recently reminded me that the church does in fact offer us great guidance. The official guidelines that explicitly speak about diversity of orientation and gender identity are somewhat minimal, though they do emphasize a loving, pastoral response. The guidelines assure us that having a homosexual orientation is not a sin. But the particular guidelines are discussion-openers, not discussion-closers. We need not limit ourselves to solely these documents. Our response is also guided by the whole social teaching of the church. These social teachings call us to respond to persons in pain, who are un-loved by their neighbours. These church documents give us methods for developing our ability to be moved with compassion.

For example, consider this passage from, Evangelium Vitae (Par 101), which Pope St. John-Paul II sends to all people of goodwill, especially believers:

“A society lacks solid foundations when, on the one hand, it asserts values such as the dignity of the person, justice and peace, but then, on the other hand, radically acts to the contrary by allowing or tolerating a variety of ways in which human life is devalued and violated, especially where it is weak or marginalized.”

It is a grim reality that LGBTQ persons face hatred, denigration, lack of access to employment, and finally injury or even death. But even when this is not the case, we are still called to love those whom others refuse to love. As church communities we are being called to educate ourselves and one another on the need for justice for the LGBTQ community.

I construe this education of ourselves in LGBTQ matters as a point of personal spiritual growth. This education might begin in confluence with other educational initiatives like those combating racism, sexism, and forms of economic injustice.

To grow spiritually, we look to the concrete, real-life experiences of our neighbours. We seek to encounter the marginalized and rejected and be friends to them, listening to their stories. This personal growth may bear fruit in many subtle ways. It may be as grand as a stranger who feels accepted by a church they’d thought rejected them, or it may be as small as a colleague who notes your use of inclusive language. In either case, you are showing that you are a person of love.

On the most basic, human level, we’re called to say “I love you,” over and over again. Policies and analysis and criticism can come later. First we look our neighbour in the eye and acknowledge their humanity. We cry with their hurts. And we tell them that God holds them in a loving embrace. This is not something we are merely “allowed” to do. This is something we must do. It is one of the deepest longings of our hearts.