The movie Romero had a profound effect on me. It’s the true story of archbishop Oscar Romero, who was killed for speaking out against injustice in El Salvador. One scene in the film is based on a radio broadcast of Romero speaking at the funeral of his friend, who was assassinated by a government hit squad. Romero is devastated, unable to believe the senseless violence. Knowing that the funeral mass is being broadcast, Romero says he has a message for the people who killed his friend. “To you, murderous bretheren, I say this: that we love you. And we ask for repentance in your hearts.”

Forgiveness is a radical act. Often, however, we trivialize forgiveness as a sort of kindness reserved for friends. Do you have your own little enemies list? Think about the people you are quietly carrying a grudge against right now, people who slighted you, people who rub you the wrong way. Perhaps it feels unfair to give up your legitimate grievance against someone for the sake of charitability. That’s because it is unfair. In fact, such an act is wrong. Forgiveness is not about giving up on justice. It is part of a radical process of restoring justice which the Christian tradition has come to call reconciliation.

Our culture tends to view conflicts in terms of rights and infringements. This makes it easy for us to forgive little things. “I’m sorry I was late for your meeting!” This acknowledges that one has minorly infringed upon the other. The other replies, “don’t worry about it.” The other gives up the claim to a grievance. In fact, the amount it would cost for the one to make it up to the other is so minor that the other can magnanimously waive it The situation gets sticky when the stakes get higher.

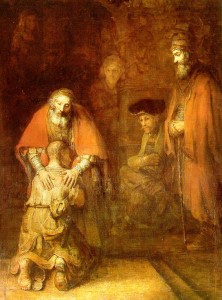

Jaques Derrida remarked that forgiveness in its truest form is only ever of things for which no amends can be made. Forgiveness of this kind, seen from a purely materialist lens, is impossible or at least paradoxical. For a murderer, no amount of remorse can restore the life of the one murdered. And yet, how can justice be served? We have a choice as humans either to continue to exact as much punishment as we can or to tearfully walk up to the hard road of reconciliation.

The face-to-face encounter is vital to the process of reconciliation. What keeps people our enemies is the fact that we do not know them and do not wish to know them. We falsely believe that to understand the other is to condone the wrong they have done. Far from it, the more we understand someone the more we will reject any wrongdoing in their actions. Through understanding, we come to see the person as more than their actions. We come to see them as a place of possibility where choices for the good can still be made. We can call that person to live justly.

Calling someone else to live justly supersedes the cost of the amends we think we are owed. We turn together, side by side as human beings, and agree that we are both accountable to justice itself. This creates the possibility for reconciliation between us.

In the wake of tragedies, our culture tends to follow a doctrine of uniting against our enemies, to unify in our condemnation the wrongdoer. But even the wrongdoer has the possibility to join us in condemning the wrong done. Condemning in itself is not a resolution; it is a first step. The next step is the exercise of our human freedom to seek to understand what is going on, to promote a face-to-face encounter between those who see each other only as enemies and not as people. This is the hard part.

Jesus was falsely accused. He was sentenced to be executed unjustly. We can often overlook his radical act of reconciliation on the cross: “forgive them, Lord, they know not what they do,” as a sheep-like act of kindness or as the largesse of a powerful God masquerading as a human. Neither of these are true. Jesus’ radical act of forgiveness is the true model for all forgiveness.

Even as we acknowledge the deep wrong that has been done, even as we find no remorse in the enemy, even when there is no hope that amends can me made, we can love. We can choose to be human and call others to be the same by seeing and truly responding to their humanity.