We are nearing the fourth anniversary of the 64th Cannes Film Festival of 2011, where a metaphysically probing and visually dazzling film won the Palme d’Or, the highest prize at the premiere international film competition. The Tree of Life was only the fifth film from American director Terrence Malick in a forty-year career, and the film has remained something of an enigma. It has been lauded as a masterpiece and dismissed as an indulgent artiste-project. What is undeniable, however, is that it managed to capture the imagination of both the mainstream Hollywood set, whose A-list actors vie to perform in the rare Malick projects, and of the more thoughtful critics from academia and religion.

I hope Malick would not take insult in hearing me describe his films as “impressionistic”. His monumental 1998 war film The Thin Red Line, for example, was less about grit and guns, and more about lingering shots of light streaming through forest canopies while soldier-muse voiceovers provided fodder for existential querying. The Tree of Life is similar, but takes us even further, proposing certain glimmers of answer to life’s most intimate questions.

As a narrative, Malick’s films prefers portraiture to tale-spinning. The Tree of Life presents us with the picture of a young family in Waco, Texas in 1956, and focuses mostly on the eldest son Jack (Hunter McCracken) as he struggles with his loss of innocence and coming to terms with two “ways” in life: the way of “grace”, represented by his luminous mother, Mrs. O’Brien (Jessica Chastain) and the way of “nature”, the win-at-all-costs philosophy represented by his father (Brad Pitt). There is a flash-forward to 1968, when his mother receives a telegram telling of the death of another son (presumably in Vietnam), and a flash-forward to present day, where we see an adult Jack (Sean Penn) grapple with the memories of his childhood and the legacy of his choices. The film also ends with scenes at mysterious seashore in an eschatological future, where the child and adult Jack interact with his parents, and where we sense the reconciliation of all things awaits.

Malick grapples with the question of “nature” in all his films, and it’s an issue that resonates with us moderns, who also struggle with understanding the cosmos we live in. On the one hand for Malick, nature is the realm of tranquility, beauty, and wonder, almost the habitation of the divine. At the same time it has a Darwinian dimension, especially manifest in the destructive encroachments of human beings. He asks plaintively, where does all this achingly beautiful glory come from? And at the same time, why this eruption of violence and cruelty?

He poses the question in a sort of binary way in The Tree of Life, through the voice of the Chastain’s mother-figure: “The nuns taught us there were two ways through life – the way of nature and the way of grace. You have to choose which one you’ll follow.” Yet, as the film reveals, these are not necessarily two separate and irreconcilable paths. There is never any path of “pure nature”, nor any “pure grace”, but the two work together, as Thomas Aquinas observed: Gratia non tollit, sed perficit naturam. Grace does not destroy or negate the laws of the natural world. Rather, grace sanctifies, renews, ennobles and elevates nature. In the film, however, “nature” seems to be short-hand for the world without God, a world that fights on its own strength and laws alone, and “grace” means that same world, transformed by God’s love.

The question of evil is an age-old philosophical (and personal) question, for which there are no easy answers. Indeed the problem of “theodicy” – how can a good God let evil things happen – remains a valid query, probably until the end of time. The great poets and saints, artists and writers help us come to terms with it, to catch glimpses of transcendent meaning behind suffering. Malick’s film deserves to be in their august company. He builds upon the tradition of the wisdom literature, with a particular allusion to Job at the very start of the film:

“Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth? When the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy?” – Job 38:4,7

God is asking a question, but it’s also an answer to a previous question from Job. Job has been stripped of everything he owned, his children have been killed and his body riddled with disease. His accusers invite him to curse the God that he loves or to admit that his suffering is due to a sin that he did not commit. Instead, he posed the question “why?” to God, and God responded with a question of his own. It’s an unexpected, greater question, one that will burst all Job’s boundaries and categories. God does not wish to give a purely conceptual answer, but invite him to view the larger context in which his problem arises. Just as it is hard for us to understand God’s response to Job, it may not be easy for us to understand Malick’s in The Tree of Life. There is much that can only be unpacked and decoded over time; we see through mirrors dimly. But God would have us know that his ultimate plan was one that had music and great joy.

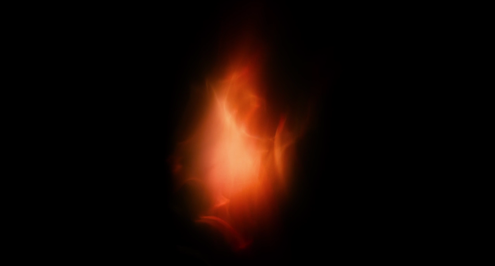

Another hermeneutic hint for decoding the film comes in the very first image of the film. A mysterious, flame-like orb of light appears, and we hear the voice of the adult Jack whisper breathlessly:

“Brother, Mother, it was they who led me to your door.”

If Jack is addressing his brother and mother, who are the “they” that led him, and to what door? The orb of light stands at the origin of the “creation of the world” and then reappears again at the very end, as the final image in the film. If it represents the Alpha and the Omega, then it’s seems probable Jack is not speaking to his brother and mother, but addressing God, telling the unnamed divinity that his brother and mother were the ones who led him to the threshold of heaven. Since most of the film is a reflection by the adult Jack on his family, and the role that grace and loss has played in his life, this interpretation turns the entire film into Jack’s prayer. At its end, Jack takes an elevator down from his glass and steel office tower, through a door in the wilderness, and onto the shore of timelessness.

The Tree of Life divided critics. It’s overwhelming. It’s sometimes confusing. But Terrence Malick at least had the audacity to ask the most important questions of all, and put them in a film that would startle and provoke. It does not offer cheap answers, but points, I believe, to the source of all knowing, the living Light that shines from the beginning and will continue until the end which is not an end.