I have often taught Saint Paul’s Letters. Paul is popular among philosophers and literary theorists even if he is rarely read in his original context. Alain Badiou wrote on Paul and the foundations of universalism in a quite famous text and I have met many learned folks over the years whose knowledge of Paul begins and ends there. Yet finding a Paul in one’s own philosophical image is nothing new and we see it on display this week in the mouth of Attorney General Jeff Sessions.

Jeff Sessions turned to Paul to defend the Trump administration’s decision to enforce border laws in a way that separates parents from children. Around 2000 children have already been torn from their parents. For Catholics, our church condemns these actions. Cardinal Timothy Dolan has condemned these actions. Yet the passage the Attorney General cites does indeed seem to back up strict adherence to the law:

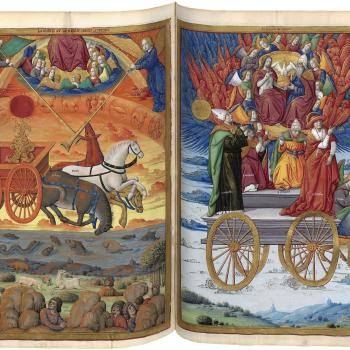

“Let every person be subject to governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God. Therefore he who resists the authorities resists what God has appointed, and those who resist will incur judgement. For rulers are not a terror to good conduct, but to bad. Would you have no fear of him who is in authority? Then do what is good, and you will receive his approval, for he is God’s servant for your good.” (Romans 13)

If this passage is isolated from the rest of the faith, then, sure, Sessions is right. But, of course, this passage is not the faith in its entirety. Paul was writing not to bolster the authority of the Roman government but to encourage his followers in Rome to be patient in persecution under Roman law. Sessions, as a representative of government, is simply not in a position to take on those words. Besides, Paul certainly didn’t take his own advice, as Cardinal Dolan points out. He was jailed frequently and according to some church traditions was martyred by Roman authorities for his beliefs.

If the Attorney General were to read Romans 12, he would see a greater challenge to his decisions:

“Let love be genuine; hate what is evil, hold fast to what is good; love one another with brotherly affection; outdo one another in showing honor. Never flag in zeal, be aglow with the Spirit, serve the Lord. Rejoice in your hope, be patient in tribulation, be constant in prayer. Contribute to the needs of the saints, practice hospitality.”

I am sure the Attorney General would agree he is not displaying brotherly affection nor practicing hospitality to those in need.

This is a reminder to all the faithful that a bible passage is not a bludgeon with which to end a conversation. As Catholics, we understand scripture within the fullness of the faith and its teaching. We must read the passage Sessions turns to as an excuse for cruelty and read it, as Cardinal Dolan instructs, in the light of Christ’s instructions on how we are to be judged by God:

“Then the King will say to those on his right, ‘Come, you who are blessed by my Father; take your inheritance, the kingdom prepared for you since the creation of the world. For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me. Then the righteous will answer him, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you something to drink? When did we see you a stranger and invite you in, or needing clothes and clothe you? When did we see you sick or in prison and go to visit you?’ The King will reply, ‘Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.’ Then he will say to those on his left, ‘Depart from me, you who are cursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels. For I was hungry and you gave me nothing to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink, I was a stranger and you did not invite me in, I needed clothes and you did not clothe me, I was sick and in prison and you did not look after me.’ They also will answer, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry or thirsty or a stranger or needing clothes or sick or in prison, and did not help you?’ He will reply, ‘Truly I tell you, whatever you did not do for one of the least of these, you did not do for me.’ Then they will go away to eternal punishment, but the righteous to eternal life.” (Matthew 25: 34-46)

Part of the challenge of the Christian life is not seeing ourselves as the center of the universe. This self-denial leads us to see the other person in front of us and to comfort the sufferings of others. In this way our faith is not only about liberation from sin, but also the liberation of others. Gustavo Gutiérrez in A Theology of Liberation may have put it best:

“To be converted is to commit oneself lucidly, realistically, and concretely to the process of the liberation of the poor and oppressed. It means to commit oneself not only generously, but also with analysis of the situation and a strategy of action. To be converted is to know and experience the fact that, contrary to the laws of physics, we can stand straight, according to the Gospel, only when our center of gravity is outside ourselves.”

Sessions’s reading of Paul resists conversion. It keeps its reader too firmly in their own body, too stubbornly on earth, and too worshipping of man’s flawed laws. The beauty of reading Paul does not come from making the great apostle a trumpet for the status quo, human cruelty, and authoritarianism. It comes from seeing Paul spread the Gospel as a refugee, a prisoner, a leader, and, ultimately, a martyr.