In Hoc Paschali Gaudio1

The Sunday Gospel readings throughout Easter come mainly from the Gospel of John, and I translated the majority of them last year. I don’t flatter myself I exhausted their meaning; but, especially since it’s Year C,2 I want to spend this year rendering the Sunday lessons (more on that word in a moment). If you want to read the posts I wrote about the Gospels (mostly) during Eastertide last year, here they are:

Gospel for Easter II: The Other St. Thomas (John 20:19-31)

Gospel for Easter III: Fish (Luke 24:35-48)

Gospel for Easter IV: Sheep (John 10:11-18)

Gospel for Easter V: Christ the Vine (John 15:1-8)

Gospel for Easter VI: “I Call You Friends” (John 15:9-17)

Epistle for Ascension: The Ascension (Ephesians 4:1-13)

Introduction to Whit Sunday (Pentecost): “Twelve Hours in the Day,” Part 1

Gospels for Whit Sunday (Pentecost): “Twelve Hours in the Day,” Part 2 (John 7:37-39, 20:19-23)

Gospels for Whit Sunday (Pentecost): “Twelve Hours in the Day,” Part 3 (more on John 20:22-23)

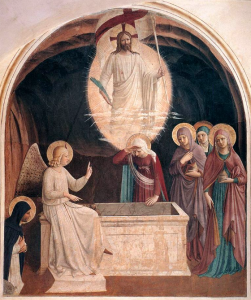

Women at the Empty Tomb (1446), by Fra Angelico.

The Role of Acts in the Bible

There are three types of readings at Sunday Mass: in Anglican terminology, they are known as the Lesson, the Epistle, and the Gospel. The Gospel reading is, well, exactly what it says on the tin, while the Epistle normally comes from—wait for it—the epistles.

The word “lesson” descends from the Latin lēctiō, which simply means “reading”; in principle, the Lesson can kind of come from anywhere, though Lessons normally come from the Old Testament. But in Eastertide, they’re drawn from the book of Acts instead. This has always struck me as a little bit funny, since Eastertide ends on the day Acts (almost) begins—it would kind of make more sense to start reading from Acts on Ascension Thursday, and continue down to some symbolic date. But this does in some ways make the most sense, if we want all the Eastertide readings to come from the New Testament.

Now, Acts is an odd book in some ways. It’s the only book of straightforward history in the New Testament, for one thing. Several books of the Old profess to be such; and obviously the Gospels claim to be histories or biographies of a kind, but even someone who considered them historical to the last detail would likely hesitate to call them histories, without qualification—they’re doing something different from that, so to speak.

… Or is Acts straightforward history? In posing this question I don’t mean “Is Acts historically reliable?”, but “Is it doing the same kind of thing as most histories, or something more like the Gospels?” I’d argue the latter. Acts has, on occasion, been referred to as “the Gospel of the Holy Ghost,” and it is the Holy Ghost’s activity that the author seems to be tracing throughout—first with St. Peter at the center, then, a little less than halfway through, switching focus to St. Paul.3

Jesus Resurrected, Accompanied by SS. Peter

and Paul and Two Angels (1556), by Anthonis

Mor. I found this by chance, and was so arrested

by how odd it is, I had to share it.

Moreover, while we cannot be certain of this, the structure of the New Testament may have been modeled on that of the Old.4 Both the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament open with the Pentateuch, the five books of Moses. (Though it was thought of as unitary, the division into five subsections, corresponding to our Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, dates back at least to the Septuagint, which is also where we get those names for them.) The Gospel of Matthew seems to be playing upon this, gathering much of Jesus’ teaching into five discourses, which fits into its picture of him as the new Moses; likewise, John speaks at length of a “new commandment.”

And how does Deuteronomy end? Moses is buried secretly, by God, and Joshua—or to give the name its Greek form, Jesus—leads the Israelites into Canaan, with the spirit Moses had resting upon him. Much later, God’s anointed, King David, conquers the city of Jerusalem, which until then had been a stronghold of the Canaanites; it is there that the Temple on which God’s glory shall rest will be built by his son. In the fifth book of the New Testament, Jesus, already identified again and again as the anointed Son of David, is taken up, and “a cloud”—the constant image of the Shekinah—”receives him from their sight,” and then the Spirit who fell upon Jesus at his baptism is radiantly poured out, and his emissaries lead forth the new children of Israel, ultimately crossing over the waters and claiming a city that had formerly been a stronghold of resistance to the Lord their God.

The Mount of Olives at sunset. Photo by

Andrew Shiva, used under a CC BY-SA

4.0 license (source).

In any case, the passage I’ve translated here encompasses the lessons from the second and third Sundays of Easter, and then some—it was ultimately such a lengthy text that I not only followed my usual habit of putting the parts not read at Mass in grey, but, where there were two whole paragraphs of grey text, I put those in small type to save room. As the passage is rather long, I tried to aim for “few, but important” with the notes; I also kept the device of putting the footnote letters in bold, because I felt that aided the eye nicely.

So! Without further ado, here is most of Acts 5.

Acts 5:12-41, RSV-CE

Now many signs and wonders were done among the people by the hands of the apostles. And they were all together in Solomon’s Portico.a None of the rest dared join them, but the people held them in high honor. And more than ever believers were added to the Lord, multitudes both of men and women, so that they even carried out the sick into the streets, and laid them on beds and pallets, that as Peter came by at least his shadow might fall on some of them. The people also gathered from the towns around Jerusalem, bringing the sick and those afflicted with unclean spirits, and they were all healed.

Butb the high priest rose up and all who were with him, that is, the party of the Sadducees, and filled with jealousy they arrested the apostles and put them in the common prison. But at night an angel of the Lord opened the prison doors and brought them out and said, “Go and stand in the temple and speak to the people all the words of this Life.” And when they heard this, they entered the temple at daybreak and taught.

The Liberation of St. Peter From Prison

(1371), by Jacopo di Cione.

Now the high priest came and those who were with him and called together the councilc and all the senate of Israel, and sent to the prison to have them brought. But when the officers came, they did not find them in the prison, and they returned and reported, “We found the prison securely locked and the sentries standing at the doors, but when we opened it we found no one inside.” Now when the captain of the temple and the chief priests heard these words, they were much perplexed about them, wondering what this would come to. And some one came and told them, “The men whom you put in prison are standing in the temple and teaching the people.” Then the captain with the officers went and brought them, but without violence, for they were afraid of being stoned by the people.

And when they had brought them, they set them before the council. And the high priest questioned them, saying, “We strictly charged you not to teach in this name, yet here you have filled Jerusalem with your teaching and you intend to bring this man’s blood upon us.”d But Peter and the apostles answered, “We must obey God rather than men. The God of our fathers raised Jesus whom you killede by hanging him on a tree. God exalted him at his right hand as Leader and Savior, to give repentance to Israel and forgiveness of sins. And we are witnesses to these things, and so is the Holy Spirit whom God has given to those who obey him.”

When they heard this they were enraged and wanted to kill them. But a Pharisee in the council named Gamaliel,f a teacher of the law, held in honor by all the people, stood up and ordered the men to be put outside for a while. And he said to them, “Men of Israel, take care what you do with these men. For before these days Theudasg arose, giving himself out to be somebody, and a number of men, about four hundred, joined him; but he was slain and all who followed him were dispersed and came to nothing. After him Judas the Galilean arose in the days of the census and drew away some of the people after him; he also perished, and all who followed him were scattered. So in the present case I tell you, keep away from these men and let them alone; for if this plan or this undertaking is of men, it will fail; but if it is of God, you will not be able to overthrow them. You might even be found opposing God!”

So they took his advice, and when they had called in the apostles, they beat them and charged them not to speak in the name of Jesus, and let them go. Then they left the presence of the council, rejoicing that they were counted worthy to suffer dishonor for the name.h

Acts 5:12-41, my translation

Through the hands of the emissaries, many signs and portents took place among the people; and they were all of one mind in Solomon’s Colonnadea; none of those left dared to stick with them, but the people regarded them highly; moreover, the faithful were added to by the Lord in number, in both men and women; so that they even carried the diseased into the broadways and put them on cots and mats, so that if Rocky came by, his shadow might overshadow some of them. A multitude also came together from the cities all around Jerusalem, carrying the diseased and those disturbed by unclean spirits—the whole lot of them were healed.

Thenb the high priest arose, and all who were with him, being of the faction of the Sadducees; they were filled with fervor and laid their hands on the emissaries and put them in public custody. By night, the Lord’s messenger opened the door of the guardhouse, leading them out, and said: “Go, stand in the Temple and speak to the people the whole message of this life.” They listened, went into the Temple at dawn, and taught.

The Second Temple, as depicted in the Holyland

Model of Jerusalem. Photo by Wikimedia

contributor Ariely, used under

a CC BY 3.0 license (source).

Then the high priest arrived, and those with him called together the Sessionc and all the elders of the sons of Israel, and sent word to the custodial-house to bring them. But the attendants on arriving did not find them in the guardhouse, so they sent back word that “We found the custody-house shut, secure in every way, and the guards standing at the doors, but opening it we found no one inside.” As they listened to these words, the governor of the Temple and the high priests were baffled about what could possibly have happened.

Then, someone arriving brought them the message, “Look, the men whom you put in the guard-house are standing in the Temple and teaching the people.” Then the governor with his attendants went out and led them in—not by force, for they feared the people, lest they be stoned. So they came and stood before the Session.

And the high priest interrogated them, saying, “We formally commanded you not to teach in that name, and look, Jerusalem has been filled with your teaching, and you intend to bring that person’s blood upon us.”d

In reply, Rocky and the emissaries said: “It is necessary to obey God rather than men. The God of our fathers woke Jesus, whom you dealt with,e hanging him on a tree; God lifted him up as founder and savior to his right hand, to give a change of heart to Israel, and remission of sins; and we are witnesses of this message, and so is the Holy Spirit which God has given to those who obey him.”

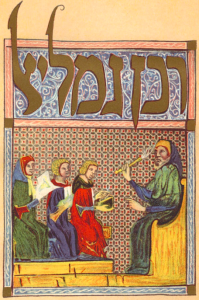

Gamaliel, depicted in the 14th-c. Sephardic

manuscript known as the Sarajevo

Haggadah. The Hebrew at the top reads

“Rabban Gamaliel.”

Hearing this, they were cut to the quick and intended to get rid of them. But someone in the Session arose, a Pharisee named Gamaliel,f a teacher of the Law honored by the whole people; he directed the men to be put outside quickly, and said to them: “Men, Israelites, take heed of yourselves in whatever you are about to do to these men. For in the old days, Theudasg arose, saying that he was someone, at which a number of men took his part, about four hundred; he was got rid of, and all who had been persuaded to follow him also turned into no one. After that, Judah the Galilean, in the days of the census, also put himself in front of the people; that man too was destroyed, and all who had been persuaded by him were dispersed. So I tell you this now—stay away from these people and dismiss them; because if this intention or this work is human, it will be dissolved, but if it is of God, you will not be able to dissolve them; and may you never find yourselves God-fighters.”

They were persuaded by him, and, calling the emissaries and thrashing them, they commanded them not to speak in the name of Jesus and let them go. So they went rejoicing from the presence of the Session, because they had been deemed worthy to be dishonored for the sake of the Name.h

Textual Notes

a. Portico/Colonnade | Στοᾷ [Stoa]: In technical terms, judging from Josephus’ description of the Temple, this was a peristyle—a covered walkway bounded by pillars (and sometimes a wall on one side) enclosing an interior courtyard. In Medieval ecclesiastical architecture, peristyles were rather favored, especially in churches attached to monastic houses, and they received the Latin name claustra, “enclosures”; this is the ultimate ancestor of the English cloister.

b. But/Then | δὲ [de]: The time frame in Acts is rather vague in most places; surprisingly few of its events can be fixed in terms of what’s called absolute chronology, the kind that offers information like “such-and-such happened in year X.” The other kind is relative chronology, which offers information like “such-and-such happened after so-and-so was consul”; Acts has plenty of this, but almost none of it can be securely pinned to particular years. Given that St. Paul spends much of the 40s going on missionary journeys, and has already been a Christian for some while at that point, his conversion must have been by the mid-30s at latest, which puts the martyrdom of St. Stephen around the same time—say, 33-35. That probably places the first five chapters of Acts within the first year or two of the Church’s existence. However, see note g for a possible problem with this timeline.

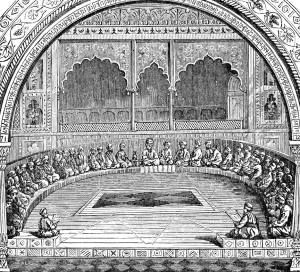

Artist’s rendition of the Sanhedrin from

an 1883 encyclopedia.

c. council/Session | συνέδριον [sünedrion]: This refers to the Sanhedrin; the Greek means literally “a sitting together.” Drawing on my Presbyterian childhood, I opted for the term “Session” as a translation, both because that is the name of the assembled elders of a congregation in that tradition, and because it is etymologically correct: it comes from the Latin sedēre “to sit.” There were local Sanhedrins of twenty-three members, which functioned a bit like district courts, but when the New Testament speaks of “the Sanhedrin,” it means the seventy-one member Great Sanhedrin that met in Jerusalem.

The Great Sanhedrin was led by its Nasi (“prince”) and his second-in-command, the Av Beyt Din (“father of the house of justice”). The high priest had originally served as its head; however, at some point before the Maccabean Revolt of 167 BC, the Sanhedrin lost confidence in the then-regnant high priest—who was apparently either Onias III or Jason,5 the infamous Hellenizer of II Maccabees 4:7-17 and other passages—and instituted the office of Nasi, while retaining the high priest as a default member. It served as the governing body of Judaism as a faith, with or without Jewish political independence.6 Membership consisted primarily in Levites, though it was also open to men of sufficiently pure Jewish lineage that their daughters were eligible to marry priests. The Sanhedrin met daily, excluding sabbaths and festivals, but not all seventy-one needed to be present every day. A twenty-three member “panel” selected from among its members could deal with many matters, provided they were not of national importance. (Given that Nazarene sympathizers like Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus were apparently not present, and that a twenty-three member court would have been easier to collect in the middle of the night in any case, it seems probable that the “special session” which convicted Jesus was of this type.)

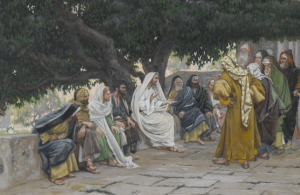

The Pharisees and the Sadducees Come to Tempt

Jesus (1894), by James Tissot.

In the later Second Temple period, the Sanhedrin was staffed by both Pharisees, who were the Judaic mainstream and usually in the majority, and Sadducees, who were drawn principally from among priests.7 This often proved a source of tension, as the two groups had radically different views of the Torah. The Pharisees (the party to which Jesus belonged—yes, really) believed that the Written Torah was, and always had been, accompanied by an Oral Torah: This was a set of principles for interpreting the Written Torah that were passed down along with the text. Pharisees also accepted certain books written by prophets and sages as holy Scripture alongside the Torah, and, partly on the authority of these additional books, they accepted ideas like the immortal soul, a panoply of angels, and some elements of apocalyptic theology (notably the resurrection of the dead and the final judgment). Still, they did not go as far in this direction as the Essenes did; among other things, the Pharisees were political quietists, arguing on the whole that God would deliver the Jews from foreign domination if the Jews devoted themselves to observing the Torah, and that no kind of violent uprising was either necessary or desirable.

The Sadducees rejected not only the additional books the Pharisees would add to the Bible, but the Oral Torah itself. In their view, they, as the priestly class, had Judaic law and ritual quite squared away, thank you very much, and they had no truck with all this superstition about “eschatology” and “immaterial spirits.” You served God until death, and then you were dead, and that was that. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they were neither Zealot-like rebels nor interested in even the more muted discontent of the Pharisees—they were active collaborators with the Herods and with Rome.

A depiction of a Sadducee from the 15th-c.

Nuremberg Chronicle. Yeah, this is 100%

what they looked like; the artist relied on

contemporary photographs.

d. you intend to bring this man’s blood upon us/you intend to bring that person’s blood upon us | βούλεσθε ἐπαγαγεῖν ἐφ’ ἡμᾶς τὸ αἷμα τοῦ ἀνθρώπου τούτου [boulesthe epagagein ef’ hēmas to haima tou anthrōpou toutou]: I imagine the sitters of the Sanhedrin did not see the concealed joke here, though I have to think at least one or two of the Apostles noticed. When Moses inaugurated the Sinaitic Covenant, acting on God’s explicit instruction, he took the blood of sacrificial oxen and sprinkled it both on the first copy8 of the book of the Law and on the people, signifying their incorporation into the covenant the book embodied.

“I’m not asking for anybody’s bleeding charity.”

“Then do. At once. Ask for the Bleeding Charity. Everything here is for the asking and nothing can be bought.”9

e. whom you killed/whom you dealt with | ὃν ὑμεῖς διεχειρίσασθε [hon hümeis diecheirisasthe]: This is properly part of a larger, extremely involved, and rather delicate discussion about the New Testament and its relationship to anti-Semitism. We can’t stop for that now; or rather, I personally can’t, because my thoughts aren’t sufficiently well-organized to set down—I mean, “anti-Semitism is bad” is perfectly well-organized, but I dare say most people wouldn’t find it a fully satisfying discussion of this text, or of the New Testament as a whole. Suffice it to say the following for the present.

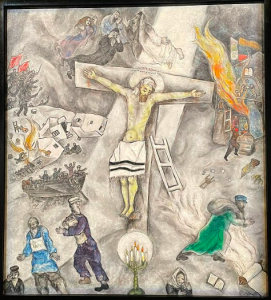

White Crucifixion (1938), by Marc Chagall.

Painted in response to Kristallnacht. Photo by

former Wikimedia contributor Kunstwollen.arte,

used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

Contrary to those who would wish, on ostensibly Christian grounds, to pry open some room under this text for anti-Semitism to kip in, St. Peter’s words cannot reasonably be interpreted as assigning blame to the whole Jewish people (of which, at the time, the entire Church were members). His words don’t blame the Great Sanhedrin as an institution; they don’t even necessarily indicate all the members of the then-present Sanhedrin. He is addressing a particular high priest, and a particular Sanhedrin, and to all appearances he’s doing so not long after the Passion itself. The high priest in question may easily still be Caiaphas, who remained in office until 36; if the aforementioned possibility (second paragraph of note c) holds, he need not be describing anyone beyond those twenty-three men—less than a third of the institution as a whole.

If you’re wondering why I address this at all, well, I sorely miss the days when we didn’t need to spell out that anti-Semitism is not only bad, not only stupid, but profoundly and irrevocably anti-Christian. Unluckily for me, we seem to have left those days behind some time in the first century. I’d certainly rather spell it out than allow anybody the space to try and keep corrupting the faith with it.

f. a Pharisee … named Gamaliel/a Pharisee named Gamaliel | Φαρισαῖος ὀνόματι Γαμαλιήλ [Farisaios onomati Gamaliēl]: This would be Gamaliel I, a grandson of Hillel the Elder. He was the Nasi of the Sanhedrin from 30 to 50, and is spoken of highly in the Mishnah; the Apostle Paul is said to have studied under him. Christian sources claim that Gamaliel I converted to Christianity (and even that he was baptized by his former pupil Paul), but did so covertly, in order to go on aiding Christians from within the Sanhedrin.

g. Theudas | Θευδᾶς: Dangit, Luke. Or, more probably, dangit, Josephus.

“You ruined everything, ruiner!”10

Okay, so here’s the problem. As we’ve said, to all appearances, this scene occurs in the early 30s. Except that’s impossible, because as Josephus tells us, the rebellion of Theudas took place in the middle 40s—he died in 46!

Actually, this isn’t a very big deal. There were other Theudases (Theudai?), and no shortage of local insurrections in Judea as the first century wore on.11 Not only is it perfectly possible that St. Luke or Josephus made a mistake, mixing up one year or one Theudas with another—it’s also perfectly possible, and in my opinion likeliest, that they’re simply talking about different events. This is even more probable because the next person Gamaliel mentions, “Judah the Galilean,” was active during the census that took place under Quirinius, which happened in 6 CE; I for one find it far easier to believe that another Theudas also staged a revolt than that Luke (whom, as I’ve related elsewhere, I think was probably writing in the early 60s) thought an event that occurred less than twenty years before—quite possibly within his own adult lifetime—had actually happened over fifty years earlier! However, this is a known puzzle in New Testament scholarship, and I don’t like to pass over those things without acknowledging them just because they don’t perturb me personally.

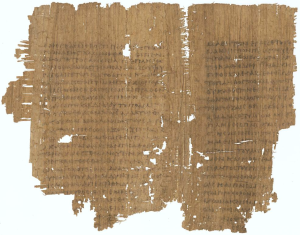

Papyrus 8, a fourth-century manuscript

containing parts of Acts 4, 5, and 6.

h. rejoicing that they were counted worthy to suffer dishonor for the name/rejoicing … because they had been deemed worthy to suffer dishonor for the sake of the Name | χαίροντες … ὅτι κατηξιώθησαν ὑπὲρ τοῦ ὀνόματος ἀτιμασθῆναι [chairontes … hoti katēxiōthēsan hüper tou onomatos atimasthēnai]: Here, we find something contemporary American Christianity seems to have lost touch with more or less completely. I mean the apostles’ direct obedience to the command contained in this text (which I’ve underlined, as we are strangely apt to miss the fact that this is a command):

Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness’ sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake. Rejoice, and be exceeding glad: for great is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you.

—Matthew 5:10-12

Since I was a child, it has struck me how utterly the church in America doesn’t believe what Jesus said here, and doesn’t do what he told us to. I’ve been listening to Christians protest, fulminate, and complain over minor—and to be frank, sometimes imaginary—slights and injuries that may possibly be for righteousness’ sake, at the same time that there are countries where a person can be lawfully put to death for confessing the Name. It wouldn’t be pretty behavior from anyone. From the disciples of him who jested sweetly to his followers, while inwardly preparing for his own death, “Cheer up, boys; I’ve conquered the universe,” and meant it—it’s pathetic.

But, perhaps I shouldn’t be getting so bent out of shape about it. He’s conquered the universe.

Footnotes

1This is a line from the hymn Jesu Salvator Sæculi (“Jesus, Savior of the World”), and means “In this paschal joy.”

2Years A, B, and C are terms for the three Sunday-based cycles of Mass readings used in the Catholic Church: in Year A, most readings come from Matthew, B focuses on Mark, and C upon Luke, with readings from John distributed throughout all three (though, since Mark is the shortest Gospel, Year B has more readings from John than the other two).

3We may never know the answer to this, and I assume that if we do, it’ll be something we learn after the Parousia! But, if the theory that Acts ends so abruptly because it actually wasn’t finished is correct, I wonder whether St. Luke’s plan was to conclude the narrative by bringing Peter back in beside Paul, perhaps in such a way that they each got about half the narrative and closed out the book side by side in Rome.

4I personally suspect that it was, and more particularly that it was modeled on the Tanakh rather than the Septuagint (the former is the Hebrew Bible, the latter the first authoritative translation thereof into Greek). Consider the New Testament’s references to “the Law, the Prophets, and the Psalms,” always in that order; now compare that with the Tanakh’s Torah (law), Nevi’im (prophets), and Kethuvim (writings)—bearing in mind that the only pure apocalyptic material in the Old Testament is found in the book of Daniel, which in the Tanakh is found among the Kethuvim, not with the Nevi’im as the Septuagint places it.

5I thus hedge, because about the only sources I could find were Wikipedia articles, which 1. I’m hesitant to give my full confidence to in the first place, and 2. that aside, there are discrepancies in the particular articles I found. (Sefaria does have an abundance of articles relating to the tractate “Sanhedrin,” part of the Mishnah, but my grasp of the Mishnah is as amateur as it gets, and anyway, its purpose is as a compendium of religious law, not history—I’d have to comb through the whole tractate in hopes of its just happening to drop a detail that would let me deduce the relevant date, which feels like overkill for a blog post?) The, sigh, Wikipedia article on the Sanhedrin states categorically that the high priest was the head of the Sanhedrin “before 191 BCE,” and provides a source for that: So far, perhaps so good; but it doesn’t seem to source its follow-up claim that the office of Nasi was instituted in that year. It’s possible that Simon II was high priest that year—the chronology is unfortunately muddled—but if so, he doesn’t fit the profile of someone the Sanhedrin would lose confidence in at all (e.g., he is spoken of very highly in the book of Sirach). His successor, Onias III, may have been more vacillating and may have reigned in 191 BCE; okay. But then, both the article’s list of N’si’im and that of the actual article on the Nasi begins with Yose ben Yoezer, and lists him as taking office in 170 BCE. The upshot of all this is, I don’t know. It seems like it’d make the most sense for this to have happened under the high priesthood of Jason, Onias III’s successor—see above, “infamous Hellenizer”; but I don’t have definite evidence that that’s the case, and am not entirely sure where to look (and if you even think the name “Josephus” right now I will fill your shoes with expired mayonnaise—he had many nice qualities, but Josephus isn’t helping anybody clear up a chronology of anything).

6After the Jewish Wars of 66-136—the First Jewish War of 66-73, the Second (in two phases, the Diaspora Revolt and the Kitos War) from 115-118, and the Bar Kokhba Revolt of 132-136—the Sanhedrin was treated with increasing suspicion and hostility by the Roman government. Theodosius II, the eighth Christian emperor in Byzantium, outlawed the title of Nasi in 425; it is likely but not certain that the Sanhedrin ceased to exist at this point. Since then, the only serious attempt to revive it seems to have taken place under Napoleon.

7This is not to say that most priests were Sadducees. The priestly class were about the only people likely to sympathize with Sadducee theology, but many priests were instead of the party of the Pharisees; the Sadducees were a very small minority.

8Though I suppose “copy” is technically the wrong word for the first one! “Autograph” would be more strictly accurate.

9C. S. Lewis, The Great Divorce, ch. 4.

10Oh come on, copybots—this has got to be fair use. In what possible way could this impinge on the market for The Simpsons?

11The Romans had an unfortunate habit of fobbing off the government of Judea onto the corrupt and the incompetent. Antonius Felix, who had a reputation for cruelty—not necessarily an easy thing to earn under the Emperor Nero!—and kept St. Paul imprisoned for two whole years because he was hoping for a bribe to release him, was about par for the course. Even Felix, probably thanks to his Jewish wife, governed less stupidly than Gessius Florus: He managed to provoke the First Jewish War, not least by very illegally crucifying Roman citizens.