July marked the 50th anniversary of Humanae Vitae, the Papal Encyclical that solidified/clarified/revised the Church’s position on contraception in marriage. Before Humanae Vitae in 1968, there was Casti Connubii in 1930 which, to modern eyes, was even stricter than Humanae Vitae. It denounced not only any artificial means of contraception, but also any actions in marriage which worked against procreation, including what would later be known as NFP.

I think of a family story when I consider Casti Connubii: a cousin whose mother in the 1940s and 50s was urged by her parish priest to have more children (she only had four). When her mother explained she simply couldn’t afford to have more, the priest explained that the Church would help take care of her additional children. This was a moment of rupture in her faith.

Pope Francis addressed this legacy a bit in a statement that caused a splash in the press. Pope Francis explained that Catholics need not reproduce “like rabbits” to be in line with Church teaching. There was a time when Catholics were associated with massive families. My great-grandfather had twelve children.

Humanae Vitae, though it is often known for its surprising conservatism, was also a mellowing of the previous guidance, opening the door for NFP and the right of families to attempt to limit the amount of children they have. Yet, for the past fifty years, Catholics have struggled with Humanae Vitae. I remember listening to a BBC radio report on Humanae Vitae over a decade ago documenting a woman who every Saturday after the Encyclical was issued would confess that she used artificial birth control. It became a new ritual for her. A way of existing in the world and as a Catholic.

It is not my place to disagree with Church teaching, but I can’t help but reflect on the past fifty years and think of what a massive material investment being a parent has become. Gone are the days when a well-off but not ultra rich family could send eight of its children off to college and gone are the days when plentiful, secure, high-paying jobs were available to those who chose not to attend college or were unable to afford it. One child out of every five grows up in a family below the poverty line. Many more live in precarious and difficult financial circumstances. In the United States, we have no funded childcare, no federally-mandated funded maternal or paternal leave, and wide gaps in the social safety net for children.

Moral and ethical choices do not exist in a vacuum away from the economics of everyday life. Casti Connubii, which is quite strict to modern eyes, does not separate its teaching from an economic imperative:

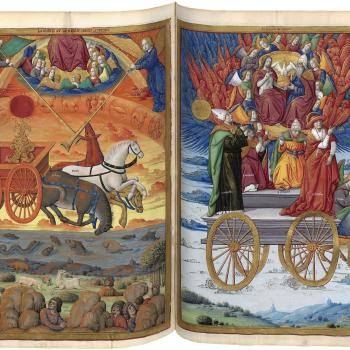

“Hence it is incumbent on the rich to help the poor, so that, having an abundance of this world’s goods, they may not expend them fruitlessly or completely squander them, but employ them for the support and well-being of those who lack the necessities of life. They who give of their substance to Christ in the person of His poor will receive from the Lord a most bountiful reward when He shall come to judge the world; they who act to the contrary will pay the penalty.”

To create a world in which every couple may bring children into the world, we must see money flow from the rich to the poor. It sounds radical, but it’s not. It’s the basis of Catholic social teaching and inseparable from its sexual morality.

So while many Catholics struggle with Humanae Vitae, and it is understandable why they do, it is important for all Catholics, regardless of their opinions on Church teaching on artificial contraception, to understand that we are called to make this world hospitable to children, built with their ability to thrive in mind. We must be generous, not hoard wealth excessively, and give freely what we can. It is always easy to lecture on sexual morality. It is much harder to build economic justice in our world.