This is the first installment of a new series entitled Language Lessons. The goal here is to take terms/phrases/words from liturgical theology and explore their meaning, especially when the meaning given publicly is often wrong or incomplete.

Alternatively titled: Is it really the work of the people?

Doubly-alternatively titled: liturgy for the life of the world. Yes, that is my nod to Schmemann, first, and then to Kavanagh, second.

Perhaps its my Protestant upbringing—the majority of my time spent in low-church evangelical, Anglican parishes—or maybe it’s the overwhelming feeling in a post-Vatican II environment, but it has become all too common to hear that liturgy is “the work of the people.” That’s all well and good, it’s certainly empowering for laypeople as they cast off the shackles of medieval clericalism. Isn’t that the picture that we (in)advertently paint when describing the Reformation? But my research and dissertation writing has led me to one question:

Is that what the word leitourgia really means?

I’m not entirely convinced that it is does. At least, not in the way that everyone thinks. Leitourgia when used in its historical context does not mean “the work of the people” but more accurately “a public work on behalf of the people.” Sometimes the public work was performed by an individual and at other times it was performed by a small group/portion of the population, but it was always on behalf of the larger whole.

It would be all too easy at this point to write me/this translation off as suggesting that clergy perform liturgy on behalf of the laity. Isn’t that precisely what many of the Reformers were rejecting? Just as the Gospel is for all people so too is gospel-centered, liturgical-focused worship. So, let me state unequivocally, that I am not arguing for liturgy as a work done by those with collars on behalf of those without.

The comfort we take when claiming liturgy is the work of the people is extremely self-centered. We haven’t been able to escape the self-focus of the Reformation in over 500 years. I think that last sentence may get me into trouble with some of you. In this popular sense, liturgy means that I am a participant, that I offer liturgy as work, that the purpose of liturgy is to make every member an active part of the worship. You’ve heard it all before, right? The focus thus becomes the church itself. The “I” and the “We.” But where is the “they”?

Stick with me. You’ll soon find out where I’m going if you haven’t gotten there already, yet.

Liturgy directs of worships and aids our encounter with the Living God. Yes, it allows clergy and laity alike to actively engage in prayer, praise, lament, confession, baptism, communion, and so much more. But have we so forgotten the mission into which God has invited us that our liturgy/s is some how separated? Similarly, and I’ll explain the connect, haven’t we been arguing for decades that the church’s mission and her worship are one in the same??

The mission of the church is to help heal and restore a broken, hurt, and lost world to the loving relationship of the self-giving Trinity, to direct the praise of creation back to the Creator, to fulfill the Great Commission.

So, liturgy then isn’t necessarily a work of the people in the democratic sense—wish though we might for the early church to adhere to our sense of self and liberty—but is more logically and accurately a work of the church on behalf of the whole world. Aidan Kavanagh put it this way:

Rather, they [the church] assemble under grace and according to the canons of Scripture and creed, prayer and common laws, in order to secure their unity in lived faith transmitted from generation to generation for the life of the world.[1]

Ah, now we’ve arrived. Let’s stay awhile.

In and through the liturgy, the church shows the world the way the world is meant to be done (Kavanagh). In the liturgy we have blueprint and design for healthy and holy living: gathering, prayer, praise, song, lament, Word, Body, Blood, confession, thanksgiving, dismissal. The Eucharistic liturgy, the very source and summit of our faith and worship (Sacrosanctum Concilium) involves the self-offering of the Church before Christ and the offering of the entire cosmos before her Creator. We make our offering on behalf of the cosmos and for the salvation of the cosmos. Our prayer and worship is a cry to the triune God that all may come to know, love, and serve him fully.

As you think through the meaning of leitourgia, as you wrestle with what I (and others before me) have said, keep in mind that liturgy viewed thus is a charge to always be thinking of the Other: God and our fellow humans. Liturgy is not an act engaged in by many or something that we all do together. It is something that the church engages in together for the benefit, blessing, and uplifting of all creation. It is the public work of Christ’s body on behalf of the cosmos, that she might be transformed in Christ to what she was always intended to be. A subtle, simple shift? Yes, but it is a shift in our understanding that makes all of the difference when we gather together for prayer and praise, for Trinitarian worship, for bath, body, and blood.

You May Also Enjoy: Fridays With Fr. Kavanagh and Liturgy and God’s Redeeming Work.

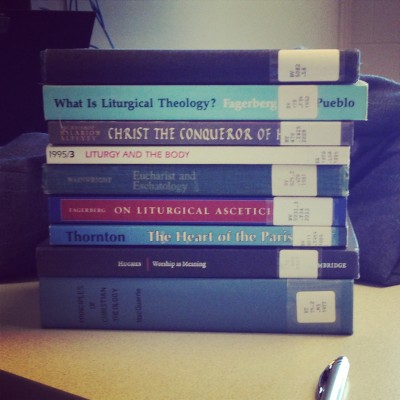

[1] Aidan Kavanagh, On Liturgical Theology (Collegeville, Minn.: The Liturgical Press, A Pueblo Book, 1984).