The Trump Administration has sought to bar Muslim immigrants from our shores. Hundreds of years ago, Americans forced countless Muslims to “immigrate” here.

Over the past few days, I’ve been reading Peter Manseau’s 2014 book One Nation, Under Gods: A New American History. In it, he deflates the myth that America is a “Christian nation” and outlines the influence that so-called “marginal religions” have had on the country since its founding. One of the most interesting portions of the book, especially given our current political climate, is a chapter that examines the countless enslaved Africans who, when coerced into coming to the New World, brought with them their Islamic faith.

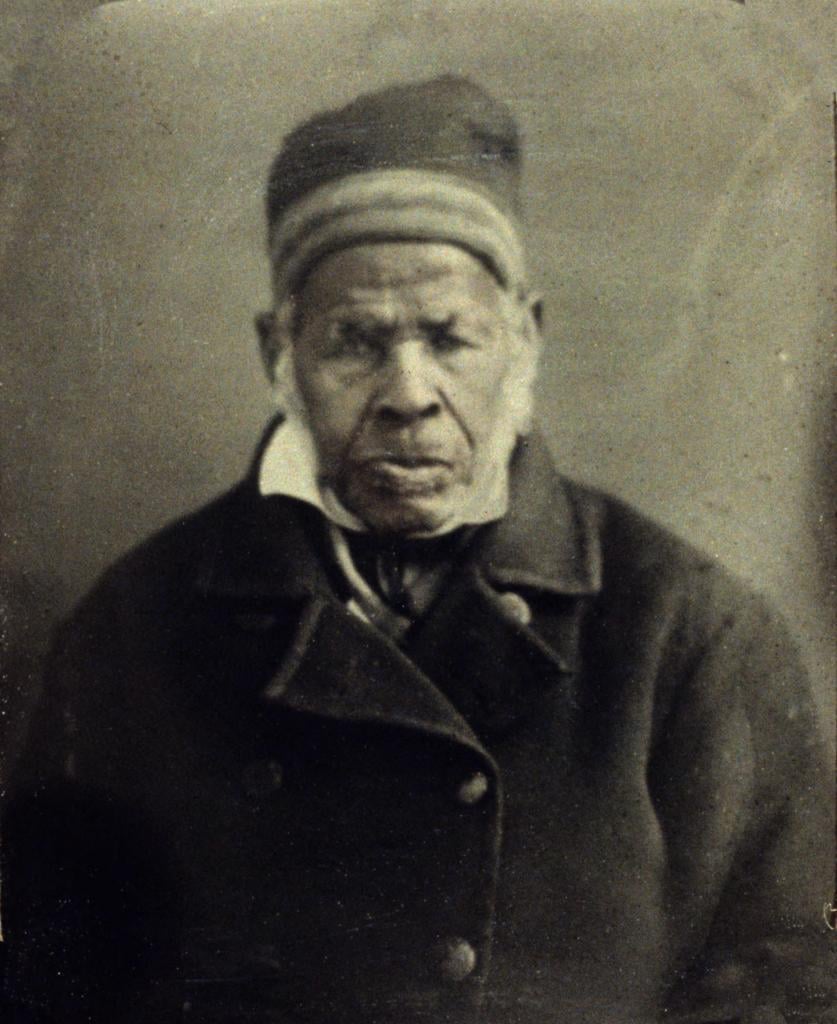

When describing America’s enslaved Muslims, Manseau cites one source that estimates that as many as 20% of those Africans brought here via the transatlantic slave trade subscribed to Mohamed’s teachings. He also details the stories of some Muslim-American slaves whose knowledge of Islamic scripture set them apart from their fellows. For example, he relates the tale of Omar Ibn Said, an affluent man in what is now Senegal who was captured by a marauding army and sold into slavery. Said would later gain popular attention when he was detained in Fayetteville, NC, during an escape attempt. While incarcerated there, Said, who had been taught Arabic by his brother who was an Islamic scholar, passed the time by using coal to write what were likely Quranic verses in Arabic script on the jailhouse walls. Rumors of his exotic scribblings spread around the countryside, and soon Fayetteville’s modest lockup was inundated with North Carolinians eager to catch a glimpse of Said’s unusual calligraphy. Perturbed by the flood of visitors to his jail, and with Said’s “owner” nowhere in sight, the county sheriff, Robert Mumford, decided to take the Muslim transplant to his home, where he assumed “ownership” of him. Later, Mumford’s family would commission Said to write his life story in what became the first Arabic-language autobiography in America, The Life of Omar ibn Said, Written by Himself.

Also chronicled in Manseau’s book is the story of Ayuba Suleiman Diallo. A native of modern-day Angola, Diallo was the son of an affluent imam who taught him Arabic. One day, he was tasked by his father with selling two of their own slaves to an English slaver on the coast. After negotiating the “sale” of his captives, Ayuba was himself taken prisoner and shipped to America. There, he was forced to work on a tobacco plantation on Kent Island, Maryland, from which he eventually escaped. After being captured near Delaware Bay, his captors noticed that he was an educated man who could write Arabic. Believing that a scholarly, literate man was not fit for slavery, Diallo’s freedom was soon purchased and he was sent back to Africa to reunite with his family.

Perhaps the most serendipitous account of a Muslim slave regaining his freedom, Manseau also relates the story of Abd al-Rahman. Born in Timbuktu, al-Rahman labored on a Mississippi plantation for forty years before a visiting Irish doctor, who had traveled through West Africa in the past, recognized him. Word of the “African prince” soon reached U.S. Secretary of State Henry Clay, who notified the sultan of Morocco of the man’s circumstances. That Muslim ruler declared that he would finance al-Rahman’s return to Africa, and the old man was soon freed from bondage and sent back across the Atlantic. Unfortunately, he died shortly after reaching the West African nation of Liberia and was never reunited with the land of his birth.

The accounts of Said, Diallo, al-Rahman, and other Muslim slaves highlight how history is often filled with irony. Hundreds of years ago, Americans forced thousands, if not millions, of Muslims to leave their homes and enter captivity in the U.S. Now, America is enduring the presidency of Donald Trump, a man who promised to ban Muslims from our nation during his campaign and who recently issued a travel ban on immigrants from six Muslim-majority countries. But while America’s position on Muslim “immigration” has changed, its underlying motivations haven’t. America once condemned Muslims to a life of servitude, based on an ideology of demonizing the other and deeming them ineffably “different” from us. Now, the Trump Administration is sentencing desperate Muslim refugees to a life spent in dangerous war zones, based once again on a bigoted characterization of our fellow human beings.