8 und nicht vielmehr also tun, wie wir gelästert werden und wie etliche sprechen, daß wir sagen: “Lasset uns Übles tun, auf das Gutes daraus komme”? welcher Verdammnis ist ganz recht.

Romans 3:8, Luther Bible 1545

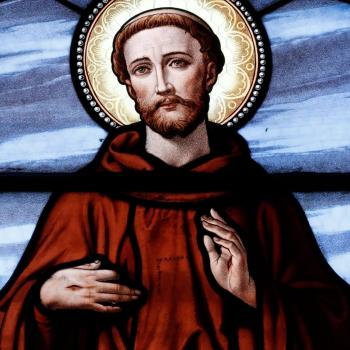

Malick’s Depiction of Blessed Franz Jäggerstätter

Terrence Malick’s latest film, A Hidden Life (2019), tells the story of an obscure Austrian peasant, Franz Jäggerstätter, during World War II. Jäggerstätter, in his refusal to sign the mandatory pledge of loyalty to Adolph Hitler, was found guilty of undermining the war effort and subsequently executed for his stance against Nazi ideology and Hitler’s regime. It was a stance however that cost him not only his earthly life. It also earned his wife, three daughters, and elderly mother the sorrow of losing a husband, father, and son, as well as the pain of enduring social ridicule from local villagers and even fellow church-goers.

Malick’s film is tedious at points, a hallmark of his style which weaves together short, choppy images meant more to evoke emotional responses than relay biographical detail. However, enough of Jäggerstätter’s story comes across as the ephemeral pictures of his life move us from an almost idyllic, pastoral existence with his family to his contentious encounters with local villagers, especially the village mayor, to a brief stint at a nearby military training camp, and then his open refusal to take the Hitler oath, his imprisonment first in Austria and then his final days in Berlin as an enemy of the state– days which ended in a war tribunal and death sentence by guillotine.

While one can nit-pick about Malick’s lack of explicitness regarding Jäggerstätter’s devout Catholic faith– Jäggerstätter was pronounced a martyr of the Church by Pope Benedict XVI in 2007 and later beatified– the film makes it clear enough that it was Jäggerstätter’s faith in Christ that made him willing to sacrifice his life and the happiness of his family for the sake of truth. One might also wonder whether martyrs like Jäggerstätter are as dour and brooding as August Diehl makes him out to be, but I will forgo this point, only suggesting that maybe they are not.

The Moral Enigma of Inconsequential Suffering

Nevertheless, there is a particular moral dilemma that runs deep throughout the film. It is an enigma Malick treats with great artistic subtlety. This moral dilemma ultimately indicts the few Roman Catholic clergy that appear in the film, the local bishop and the Jäggerstätters’ village priest. It is also the crux of the film, which supplies the movie with its title “A Hidden Life.” For in the film Jäggerstätter is repeatedly tempted to abandon his defiant stance against Hitler for the simple fact that “it will not change anything of the world” and “no one will ever know about what happened.” In other words, his defiance in the face of evil will be of no consequence.

As the various antagonists– the Nazis themselves, village friends, some family and the clergy– continually point out, even if Franz’ stance is right, even if just and even if courageous, it is ultimately pointless because it will serve no practical function. Moreover, it will go unnoticed. It won’t bring about any “greater good” and, in fact, it will certainly be the cause of concrete harm– harm not only to himself but to his family (the life of a 1940’s alpine subsistence farmer is vividly depicted by Malick, and the viewer comes away from the film with a sense of the sheer physical demands of such a lifestyle). The act, like Franz’ life, will simply be lost to time.

However, at each temptation to abandon his convictions and take the oath, an act which would facilitate the charges being dropped and even allow him to serve as an orderly in a hospital, Jäggerstätter still resists. For Franz’ stance is not one grounded in some kind of calculable set of consequences. Nor are his actions ones carefully mapped out on some pleasure versus pain matrix. It is not a stance grounded in a moral system or ethic that might allow an evil to be done for one’s own sake or even for the sake of some greater good or higher reform.

Rather it becomes clear as the film progresses that Jäggerstätter is operating from an entirely different moral sensibility. It is a sensibility that does not make such calculations, even if the natural desire for peace, happiness and safety constantly accompany his inner life. Instead, Jäggerstätter chooses to go to his death for the sake of not participating in an evil deed. His deliberations are not pragmatic, they are about truth.

And that truth is that some things are truly evil and should never, under any circumstances, find human participation. For it is in the very nature of swearing the oath itself that compels Franz to sacrifice so much, even though legitimate goods (e.g. a life with his daughters, care for his elderly mother, additional children with his wife) could have been obtained by doing otherwise. The oath is evil and the saint cannot partake in its nature, even if it would facilitate other instrumental goods.

On Not Doing Evil So That Good Might Come

One might imagine that the words of St. Paul in his letter to the Romans would have not only been known to the devoted Catholic, but that they had sunk deeply into his soul. Of course Jäggerstätter would have had something like Luther’s translation above available to him, but the ESV puts Paul’s words this way:

And why not do evil that good may come? – as some people slanderously charge us [the Apostles] with saying. Their condemnation is just.

Romans 3:8

Here Paul tells us in no uncertain terms that the Christian life will always be fundamentally different from other attempts at morality. To suggest one do evil so that some good may come, even the good of divine mercy, is slanderous and worthy of condemnation. As followers of Christ there is no true evil which is pardonable so long as there is some greater good in sight. One may not “crack a few eggs” in order to make an omelette, utilizing wicked means for otherwise noble ends. This is not to say that the ends of the Hitler oath were noble! But, we can assume that Franz’ ends, had he signed the oath, would have been. So why didn’t he?

The true Christian cannot do or support that which is intrinsically evil so that good consequences may result, regardless of how tempting those consequences might be or even how objectively good they might be. As such, this posture will always put the faithful Christian at a disadvantage to those who are worldly-wise. For while the Christian may desire the same end as the non-believer, the Christian will be bound by conscience to go about it only in ways that align with the will of God.

There are various just ends that Christians and non-Christians may both agree on, but for the Christ follower all manner of action to achieve those ends must coordinate with God’s divine law. The Christian’s options for working toward the good are, in this sense, far more limited. This fact can often infuriate those of a more secular bent, who look to Christians to act as they do and to put results first. However, it is tragic that so many Christians, myself included, capitulate or conform to the ways of the world. For in doing so, we do evil in the process.

Resisting Temptation To The End

At one point in the film, just days before Jäggerstätter’s execution, his wife, accompanied by the parish priest, visits him in the Berlin prison where Franz awaits his final moment. Again the priest, in Screwtape-like fashion, begs Franz to recant. He pleads with Franz to take the Hitler oath saying, “God only cares about what is in your heart, not about what you say.” Failing to understand that the act of speaking on behalf of Hitler’s program is itself acquiescence to evil, and even participation in it, the priest becomes not the voice of Christ calling us to transcend our weakness (to “come and die” as another German martyr would put it only a few years later), but that of the enemy, the Satan, who lures us into giving in to our weakness.

One is left to wonder if attitudes like that of the village priest had not permeated throughout 1940’s Germany and Austria, if the war would not have come to a much quicker end and many lives been spared. How might things have turned out if, like Franz, more had spoken up about what God had put in their hearts? It is a counterfactual worth contemplating, especially given our current political climate.

In the end it is Fani– Jäggerstätter’s faithful wife– who, in spite of her own fears of being left alone to raise three daughters, till the soil and care for Franz’ elderly mother, grasps the necessity of her husband’s calling. In doing so she tells him, in Christ-like fashion, “whatever you choose, I am with you.” For it is Christ who also says to us: “Look, I am with you always, to the end of the age.” In this exhortation, Fani Jäggerstätter herself joins in Christ’s sufferings for the Good, an act which should also earn her the title: hero of the faith.

Franz Jäggerstätter, martyr of the Church, knew therefore not only the companionship of a faithful wife, but the partnership of the Holy Spirit. Like John and Peter, Franz too understood that to fail to preach Christ in the midst of persecution is to adhere to the laws of men over the Law of God. Another film of similar brilliance, depicts the converse, showing what happens when men obey man’s laws instead of God’s. What Jäggerstätter further knew was that our actions speak as loudly as our words, and that often our action for the sake of Christ will mean that we speak words of truth when called to do so, and refrain from speaking falsehoods, even when put to the ultimate test.

Not Hidden, But Revealed

Jäggerstätter’s act of defiance not only resulted in his being martyred in the same manner as the Apostle Paul, but created enduring hardship for his surviving family. Moreover, had he recanted there might have been the chance to serve in a hospital and even save lives as an orderly (this is hinted at in the film, acting as another form of the same temptation). But, in the end, it was his Christian character that testified to that particular reality, that one Truth that gives us true hope and which allows us to find the strength to refrain from that which is evil. For from evil no true good ever comes. That reality that Franz understood is the Resurrection of Jesus Christ and the hope for eternal life with God.

This is however a point that will likely be missed by most if not all of the film’s critics. Most will likely see Jäggerstätter’s sacrifice as merely a tortured wrestling between something concrete and real and something abstract and obscure like a noble principle or stoic value. But, for the Franz Jäggerstätter of history this was not a choice between the concrete and the abstract, or between the real and the metaphorical, it was a choice between the finite and the infinite, between the contingent and the necessary, between the shadow of this world that is fading away and the actual world that is to come.

In a culture given over to “ends-justifying-the-means” thinking it is good to note that Jäggerstätter’s tempters were wrong on two counts: one, in that his life did change the world, as every act of pure love does, and two, in that it did not remain hidden, as both his beatification and Malick’s movie have revealed.

Note: This article first appeared under the title Hidden Yet Revealed in the March/April 2021 issue of Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity

Featured Image: August Diehl in A Hidden Life. Reiner Bajo/Iris Productions