This is the second of a four part series in which I explore theologians of the previous two centuries who contributed to the theology which today influences progressive Christianity. In the last article we looked at the father of progressive Christianity, Friedrich Schleiermacher. Today we look at one of Schleiermacher’s theological grandchildren, Walter Rauschenbusch.

Who was Walter Rauschenbusch?

Walter Rauschenbusch was born in America to German immigrants in 1861. After completing high school he studied in Germany before returning to the States for his college education. Graduating from Rochester Theological Seminary in 1886, he accepted a pastorate in the woefully poor and downtrodden neighborhood of “Hell’s Kitchen” in New York City. There he felt overwhelmed by the poverty and abuse he encountered daily, and became enamored of a gospel which places the responsibility to care for the poor solidly upon the believer.

While at university, Rauschenbusch encountered higher critical methods of biblical study which caused him to doubt some of his childhood beliefs. As is common of many classical liberal theologians, he abandoned the inerrancy of the Scriptures, adopting instead a broad source and form critical approach– especially regarding the Old Testament. Rauschenbusch even went on to question the concept of substitutionary atonement.

What Is Rauschenbusch’s Social Gospel

In 1907 Rauschenbusch wrote his first major work, Christianity and the Social Crisis. Here he explored the message of the prophets in the Old Testament, demonstrating that the prophets strove to hold the leaders of Israel to a personal accountability to God’s law, despite the crumbling monarchical national government. He emphasized that the nation of Israel fell into disarray because her leaders lost sight of the religion upon which she had been founded. Rauschenbusch wrote:

When religion was driven from national interests into the refuge of private life, it lost its grasp of larger affairs, and the old clear outlook into contemporary history gave way to an artificial scheme.

Social Crisis, 14

Rauschenbusch then turned his attention to the person of Jesus. He felt that John the Baptist, in foretelling the work of Christ, was setting the stage for a return to the world of the OT prophets. He states: “The judgement which he [John] proclaimed was not the individual judgement of later Christian theology, but the sifting of the Jewish people preparatory to establishing the renewed Jewish theocracy” (18). While initially noting that Christ was not a Social Reformer, Rauschenbusch went on to say that Jesus embraced the message of John, and built upon it with His notion of the Kingdom of God.

However, for Rauschenbusch, when Jesus uses this phrase He does so in a specific context and with a specific audience in mind. He sees Jesus as addressing the Jewish people who hoped for a return to their previous nation, not so much the radical zealots, rather the man-in-the-street whose heart longed for the stories of the prophets. Referring to the message of the Kingdom of God, Rauschenbusch asks rhetorically:

If [Jesus] did not mean the consummation of the theocratic hope, but merely an internal blessedness for individuals with the hope of getting to heaven, why did he use the words around which all the collective hopes clustered.

Social Crisis, 19

Rauschenbusch saw Jesus as a pacifist, a bringer of the peaceful movement toward the Kingdom of God. Jesus certainly meant the Kingdom would be perfected in the future when His return would inaugurate a new order on earth. Yet, at the same time, Jesus intended to convey the imperative to each of his followers to make the kingdom of God on earth by imitating him– the Christ– the One who prefers the poor and marginalized. Rauschenbusch writes the Kingdom of God “still remained a social hope. The kingdom of God is still a collective conception, involving the whole social life of man” (21).

Social Gospel or Socialist Gospel?

Here is where Rauschenbusch’s political leanings became evident. Rauschenbusch never became a member of the growing Socialist Party movement, but certainly flitted around its edges. He often wrote for socialist journals and two of his children were presidents of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society at their respective universities. Rauschenbusch would often say “I am a socialist,” emphasizing the lowercase use of the word. Of Rauschenbusch’s views, Jacob Dorn writes:

Rauschenbusch saw himself as a mediator between Christianity and socialism. His first loyalty was to the Christian ideal of the Kingdom of God as both here and yet ever coming. But the attraction of socialism as a force working toward that Kingdom was powerful.

Rauschenbusch saved his most vehement language for Capitalism, which he violently opposed. Theologian and philosopher Kirk Macgregor speaks fairly positively of Rauschenbusch overall, taking him at his word that he was not advocating for Socialism. However, a deeper reading of Rauschenbusch reveals that while he abhorred the requisite atheism of Marxism, he clearly saw the responsibility of the Church and the individual Christian to support socialist leanings in government. He failed to clarify a divide between advocating for a Christian Socialist system of national governance and the individual’s responsibility to care for his fellow person.

Rauschenbusch’s version of the Kingdom of God became in fact his impetus for the Christianization of all aspects of society, from labor and industry, to manufacturing, research, universities, even government. He chastised the Church for her land ownership and he accused her of being a modern pseudo-religious enterprise committed to making money, declaring she (meaning the Church) was a tool of capitalism. In this way he failed to see Jesus’ vision of the Kingdom of God not only including the Church but placing her foremost as God’s revelation of Himself to the world. His criticism of the Church centered on the belief that the Church had become too institutionalized, and so he wrote off the Church completely. For Rauschenbusch the only hope lie in every man carrying out the social gospel in an attempt to initiate a grass roots movement toward a Christian Socialist society.

Theology for the Social Gospel

With this statement, Rauschenbusch opens his 1917 work A Theology for the Social Gospel: “We have a social gospel. We need a systematic theology large enough to match it and vital enough to back it”. Building upon his earlier book, Rauschenbusch’s Theology seeks to establish what was missing from his earlier call to action, that is, a Christian theology which underscores the social responsibility of the believer. In this book he attempted to build the theological model for his social vision. However, he fell short in that he again pushes the Church to the background.

He states:

The social movement is the most important ethical and spiritual movement in the modern world, and the social gospel is the response of the Christian consciousness to it….It seeks to put the democratic spirit, which the Church inherited from Jesus and the prophets, once more in control of the institutions and teachings of the church.

Social Gospel, 6

Thus the social gospel or social movement becomes the purpose of the Church, rather than salvation of souls. In fact, for Rauschenbusch, people can be saved through their social work more readily than through belief in Christ. Stanley Grenz and Roger Olson declare of him: “Rauschenbusch … defined salvation as the ‘voluntary socializing of the soul”.

In this way we can continue to draw the line from Schleiermacher through Rauschenbusch as the forefathers of today’s Progressive Christianity. Schleiermacher downplayed the transcendence of God and made Him so immanent as to be in everything. He also made the individual believer’s view of God to be the only truth which can be known about Him. Rauschenbusch made what the believer does for his fellow person in the world to be the essence of their “liberalized” religion. What may be known about God becomes essentially only what work the believer accomplishes in the community, as the social gospel becomes a gospel all its own. Macgregor writes:

For Rauschenbusch, it was not Jesus’ crucifixion that invested his embodied kingdom with value, but his embodied kingdom that, consistently with his ability to take the greatest evils and invert them, brought good out of his crucifixion.

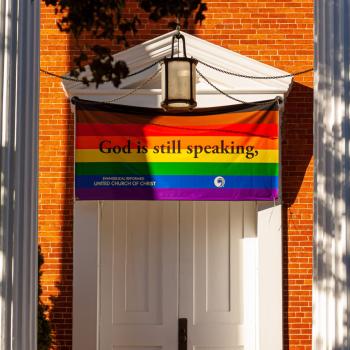

Today’s emphasis in Progressive Christianity of love and acceptance of all people at the expense of any normative or objective sense of love and acceptance is built upon the foundation that Rauschenbusch laid. The believer in the kingdom becomes saved by his or her adherence to the social gospel, and Christ’s work is primarily that of working within the human soul to bring each person to enact good in society. Is it wrong to care for the poor, the homeless, and the marginalized in society? By no means! Christ showed that clearly in His gospel. However, it is clear that Christ handed the responsibility for this first and foremost to the Church and not to government. This is where many Christians today have failed in that we have relinquished our responsibility to care for society, or, in the words of Rauschenbusch, our responsibility to the social gospel. Instead we have allowed the government to be responsible to fix homelessness, poverty and social pathology.

Whose Gospel is It: Church or Government?

Rauschenbusch decried the greed and graft of the Church, and mourned that she was so mired in self-interest. But he offered a word of hope:

If this insight [of a social gospel] and religious outlook become common to large and vigorous sections of the Christian Church, the solutions of life contained in the old theological system will seem puny and inadequate. Our faith will be larger than the intellectual system which subtends it.

Social Gospel, 6

This is certainly true. When the Church stands on the words of God in Scripture and reaches a hand to those in need, she and each of us as a community of believers, will be fulfilling our God-given role in the world. A national system is not the answer when the followers of God accept their responsibility to care for all in society. Salvation in this way is not a product of the social action, rather we preach belief in the saving work of Christ along with our social outreach. The social gospel becomes the Gospel in action.