I rarely do movie reviews, but two recent films are worth writing about: Martin Scorsese’s latest historical epic, Killers of the Flower Moon, based off a book by David Grann; and The Iron Claw, about the Hall of Fame wrestling family, the Von Erichs, directed by Sean Durkin. In these reviews, I will not be concerned with the historical accuracy of the films, nor with plot summaries, but only with their aesthetic virtues and some important theological issues that they touch on.

Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)

For the plot summary of Scorsese’s latest, see here. It is a long movie (3.5 hours), but, in short, the film is about a morally corrupt rancher, Bill “King” Hale (Robert De Niro), his family, specifically his nephew Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio), and Hale’s life-long attempt to graft his way into the community of the wealthy Osage Indians of Oklahoma. When we meet Hale, he is already a longtime resident of Fairfax, and has befriended the Osage tribesmen, learning their language and their customs. The Osage have struck it rich, the prior generation having found extensive oil reserves on their lands. This is why Hale has come to Osage territory.

Scorsese sets the film up as yet another cinematic rebuke of “the white man.” “The whites,” bound by an inherently malevolent, and unique, sin nature, are determined by that nature to oppress, abuse and manipulate the otherwise noble and pure, albeit melancholy and demoralized, natives.

Moral Types in Killers

However, Scorsese’s film is nuanced enough that it cannot be sloughed off as a simplistic, critical theory-inspired screed against all things European. At least in one regard it does not do this, namely, through its main character, Ernest. Ernest, unlike Bill, and also unlike his Osage wife, Mollie (Lily Gladstone), is a complex character, meaning that while he commits his good share of crimes and atrocities, he is not one driven by a pure lust for power, like his uncle Bill.

Instead Ernest is motivated by what theologians have long called “concupiscence:” the lust of the flesh and weakness of moral restraint. It is this lack of moral restraint which makes Ernest susceptible to unadulterated malevolence of his uncle Bill “King” Hale. Hale is himself a master manipulator and, at the heart, a criminal. Ernest may be a criminal, but, unlike Bill, he is not a maker of criminals. Mollie, alternatively, and her three sisters, all inheritors of Osage oil money, are portrayed as spotless victims. Their only sin, if any, is falling in love with the white men who wind up abusing them.

As such, we see three, basic types of moral characters in Scorcese’s film: the inherently corrupt (“King” Hale, his son Byron, the local sheriff, the town doctors), the inherently innocent (Mollie and her sisters, and all the other Osage), and the one, complex character: Ernest. Other side characters are not explored in enough detail to evaluate their moral constitution. However, the other white townsfolk are depicted as generally corrupt, and while the federal agents are portrayed as seeking justice, they are not necessarily sympathetic to the plight of the Osage, even if their professionalism is admirable. This standard typology of characters makes Flower Moon not nearly as realistic, or as interesting, as some of Scorsese’s earlier entries, like 2016’s Silence. De Niro’s character, Bill “King” Hale, feels especially flat– another of De Niro’s bland “mafioso” types, transplanted from 1940’s New York to 1920’s rural Oklahoma.

Ernest is the centerpiece of the story, and it is Ernest that makes the movie interesting. Torn between his base lust for pleasure: money, sex, gambling, liquor, and a suppressed conscience, we see Ernest wrestle with forces both inside himself and outside himself that he cannot control. He is the typical, intemperate Jedermann, who, being “tossed by wind and wave” (Jas 1:6), cannot resolve to be one way or the other; ever vacillating between virtue and vice, but usually opting for vice. We see this adeptly depicted in the film, for when Bill lies he does so with ease, untroubled by conscience. Ernest, however, feverishly stumbles and stutters every time he is confronted by truth, even if he usually gives in to lying. It is Ernest’s weak moral constitution that allows him to be easily manipulated by his uncle and his uncle’s accomplices.

However, Ernest’s moral struggle ends, and a partial redemption comes when his love for Mollie and his children engenders in him enough nobility to finally tell the truth about Hale’s campaign of exploitation and murder against the Osage. His testimony to a federal court about Hale’s notorious plot to marry into Osage families only to get their wealth brings the reign of terror to an end (although we are left to assume that Hale was not alone in this systematic rape of the Osage, their land, and their dignity).

Finally, with regard to Ernest’s destiny, he still cannot muster up the courage to come clean to his wife about his own role in the atrocities. We are told later in a “reenactment scene” (which features Scorsese himself on camera) that Ernest and Mollie divorce: Ernest ending as a drunk in a trailer park with his brother, while Mollie remarrying but dying young, likely due to all her prior trauma.

A Biblical Prototype: Flower Moon and The Story of Hamor

One thing is especially noteworthy from a biblical and literary perspective in Killers of the Flower Moon. Those familiar with the Old Testament may pick up on it: it is the parallel between the character of Bill Hale and that of Hamor, father of Shechem, in Genesis 34. In fact, Flower Moon, seems to pick up on several themes in the story of Hamor and Shechem, aka “The rape of Dinah.”

In the story, Shechem, the Hivite prince, rapes Jacob’s only daughter, Dinah. Here we see the basic prototype for the plot of Flower Moon. After Shechem, out of lust, has defiled Dinah, he goes to his father Hamor to see if Hamor can convince Jacob to give Dinah to him in marriage. Jacob, not unlike the Osage tribal chieftains who give their daughters over to the white men in marriage, considers Hamor’s proposal in spite of the disgrace Shechem has brought against his family and the nation. It may be, after all, quite practical to enter into relations with the Hivites (cf. Gen 34:30). Dinah’s brothers, Simeon and Levi, however, are more principled than their father, the old trickster. As such, they make a “deal” with Hamor that if the Hivite men circumcise themselves, then, and only then, will the daughters of Israel enter into marriage with them.

Hamor, agreeing to the circumcsion and feigning interest in the Israelites, reveals his real plan to the Hivites: to take the daughters of the Israelites in marriage, so as to get to their wealth:

So Hamor and his son Shechem came to the gate of their city and spoke to the men of their city, saying, 21 “These people are friendly with us; let them live in the land and trade in it, for the land is large enough for them; let us take their daughters in marriage, and let us give them our daughters. 22 Only on this condition will they agree to live among us, to become one people: that every male among us be circumcised as they are circumcised. 23 Will not their livestock, their property, and all their animals be ours? Only let us agree with them, and they will live among us.”

Gen 34: 20-23

The character of Bill Hale, to include his life plan, is essentially that of Hamor the Hivite. Hamor intends to integrate into the Israelite culture and use the Israelite women to get to their wealth. In the movie, Hale has already done this to a large extent: he has worked his way into the Osage culture, gradually winning their confidence. We see him already well into the the process of using the daughters of the Osage (the Israelites) to get their “livestock, their property, and all their animals,” i.e., to get all their land and oil, their “head rights” as they are called in the film. It is only Ernest finding his conscience, that prevents Hale’s nefarious plot from succeeding.

Lastly we come to the Osage tribal elders, who repeatedly threaten how “in the old days,” they would have destroyed the white men, killing them on principle for their underhanded tactics, their abuse of their women and rape of the land. Yet, unlike Simeon and Levi, and more like Jacob, the Osage elders have themselves become too practical and too comfortable in their own corruption to attend to more profound matters of honor and shame. They, like Jacob, have forgotten about honor, exchanging it instead for material wealth and, in a very real sense, for peace.

Still, it is their lack of moral outrage, and their diminished masculine vigor, which confirms Hale’s ironic prophecy that “the time of the Osage has passed.” Having become entangled with Hale’s own power, the Osage have sacrificed their ethos and identity for the shallow irenicism and economic prosperity that Hale’s counterfeit friendship has provided. Lacking among the tribal chiefs are a Simeon and Levi who stand up and resist the white Hamor saying “Should he treat our sister[s] like harlots?”

The Iron Claw (2024)

If Flower Moon sacrifices some depth and complexity in favor of narrative tropes, Sean Durkin’s biopic The Iron Claw does nothing of the sort. I am a hard critic on movies, so for me to suggest a movie rises to the level of aesthetic brilliance is quite rare. But The Iron Claw does just that. This is a brilliant piece of moviemaking that hits the right balance between realism and literary typology in its characters and story arc. Like Flower Moon, there is hardly an instance of forced or canned dialogue in Iron Claw. Nor did I hear one line that acts as a conscious allusion to some other pop-cultural product. In other words, the characters speak like real people coping with real circumstances, not like movie characters coping with movie-like circumstances. Moreover, when it comes to moral complexity, every one of the major characters is complex, just like every one watching in the audience is complex.

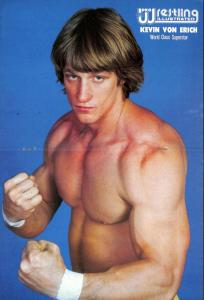

The main arc of the story centers on the relationship between the professional wrestler, Jack Adkisson (“Fritz” Von Erich was his ring name), and his sons Kevin, Kerry, David and Mike. Another son, Jack Jr, we are told died young, and a sixth son, Chris, is left out of the film due to artistic constraints. In real life, five of Adkisson’s six sons died before him, three of them–Mike, Chris and Kerry–by suicide. Only the second oldest, Kevin, is still alive today.

All of the performances in the movie are academy-award worthy (assuming the academy awards still gives out awards for artistic endeavor, and not just for artistic scandal. I wouldn’t know as I haven’t watched one since Billy Crystal hosted). Zac Efron is especially good in his depiction of Kevin, the only surviving von Erich brother, and the main character of the story. The motivation for the movie is, of course, the series of tragedies that plagues the family. Of six otherwise healthy and utterly able-bodied men, only one lived into full-fledged adulthood.

Why?

The Father Dynamic and Living Vicariously

With the exception of Jack Jr., who died by accident as a child, the reason given in the film for the other deaths is fairly clear: the obsession of one man, Jack Adkisson (Holt McCallany), in becoming a champion wrestler. Theologically speaking, it is Jack Sr.’s obsession with his own identity, his own self, that drives each of his sons, in turn, to their grave. In psychological terms, Jack’s ego is so big that he sees each of his children not as separate individuals, unique human beings, but as a mere extensions of his own self. As such, their life-goals are not their own, they are his. Each of the von Erich boys exists so that Jack can become what he always wanted to be in his youth but never did: a success. The father lives vicariously through his sons, treating them as instruments, as means to an end. It is an end that ultimately breaks each instrument, save one.

Jack’s love for his sons openly fluctuates depending on who is, at any given time, succeeding in the mission of fulfilling Jack’s dreams. At the dinner table, we see Jack openly discuss with his sons how they can rank up or down in his estimation based on how well they perform in achieving his dreams. The resulting dynamic is an extended litany of disappointment, disillusionment and death. Each von Erich son is tormented by an unrelenting and merciless expectation to perform. When they fail, they lose everything, to include the affections of their father. When they succeed, they gain little, for it was never clear to them whether what they won is what they actually wanted.

Still, Jack Adkisson is not Bill Hale. He is more complex than that. His ego is maniacal, that much is certain. However, why it is that way we do not know. We are left to wonder if his own ego is not the tragic result of some broken relationship, or set of circumstances, perhaps going back to his own father or desperate series of events. We aren’t told directly, but we feel led to speculate.

Nevertheless, Jack has some qualities worth emulating, and the film does not shy away from presenting those qualities along with the many vices. He loves his children…sort of. He is, in some genuine way, a very present husband and father– a stark contrast to the stereotypical “absent dad” of late 20th-century America. He is a provider, of sorts, and he at least tries to give his sons guidance about life and how to live it well. He tries to encourage them, he compliments their efforts, he plays with them. He is not a drunkard, a philanderer or a lout. Fans who watch combat sports, particularly boxing, will know the type, the “father-trainer” is often a great blessing and a terrible burden to the professional athlete.

As such, the character of Jack raises several deep moral and theological questions for the audience. In one scene, after David’s death, Jack speaks of God’s providence in regard to the timing of David’s early demise. In a sense, this is true; for all things do come to pass according to the will of God. However, to what extent is Jack also responsible in the deaths of his sons: where is his culpability in their untimely deaths? The answer is clearly somewhere! Even though David’s death is from natural causes, severe enteritis, the film implies that Jack’s obsession with winning drove David to do things to his body, and his mind, that lead to its breakdown. The other two deaths shown, those of Mike and Kerry, are more obviously causally connected to Jack’s unyielding narcissism. When human beings are treated like tools, the tools break.

Of Macho Men and Divine Providence

One of the themes throughout the film is Jack’s suppression of his and his sons’ emotions. When tragedy strikes, either in the form of career disappointments, like Kerry losing a limb after a motorcycle accident, there is only one response: suck it up! This type of warrior mentality is easy prey for today’s feminized commentator. The idea being to simply dismiss this kind of machismo as an outdated, and outright evil, expression of masculinity (One can already hear the Andrew Tate analogies.)

However, the issue with Jack’s attitude toward emotions is not one of kind, but of degree. In a culture where emotions have run wild, and often are leveraged against reality itself, there is a proper place for restraining the passions. Unfortunately, in the case of the von Erichs, Jack confuses emotional restraint with the total elimination of emotion. Not being allowed to cry at the death of a beloved brother is not emotional restraint, it is emotional abuse. Of course, just as abusive, is crying at each and every turn in life. Effusive and unchecked emotion diminishes the seriousness of things, which leads to confusion about how to evaluate degrees of goodness, and badness, in the world.

As C.S. Lewis pointed out in the first essay of Abolition of Man, “Men Without Chests,” it is not the elimination of emotion that will save culture, as Gaius and Titius would have it, it is the proper training of the emotions to correspond to objective moral values that sustains a society. The Iron Claw does not demonize Jack Sr.: he is trying to pass on something important to his sons. He is trying to tell them something important about manhood. That desire, in itself, is both right and good. Unfortunately, his notion of manhood is simply off. He has adopted a form of stoicism that would have been quite foreign to the stoics. He has confused the proper distancing of the emotions from things outside of one’s control with trying to control everything so as to not have to feel any emotions. This is not courage, this is fear.

And at the root of the mantra that Jack proffer’s throughout the film: ““If we’re the toughest, the strongest, the absolute best, the most successful, nothing can ever hurt us,” is just that: fear. And where one lives a life of fear, it can hardly be said that one is living a life of faith in God’s providence. If Jack had any real sense of God, or God’s providence, he would have discerned what was the right way for each of his sons, as sons, and not mere projections of his own desires. Had Jack submitted to God first, he might have recognized God’s desires for his boys, not his own, and instead of pressuring them into a pre-determined mold of his design, aided them in living a pre-ordained life of a godly one.

On Suicide and the Afterlife in The Iron Claw

There is one final topic to address: the issue of suicide in The Iron Claw. Two of the three von Erich suicides are shown in the film. The second, Kerry’s, is followed by a scene that depicts him in a place analogous to heaven. We see Kerry restored, his amputated foot now returned to him, and floating down a local river in an unmanned rowboat on a pristine summer’s eve. He eventually comes to a dock and is met by his brothers David and Mike, who warmly greet him. They start walking through a meadow together, exchanging pleasantries. Finally, Kerry asks about his older brother Jack Jr., and Jack appears, still in his earthly form of a 6-year old boy. The brothers embrace warmly and the scene concludes (anyone who fails to get teary-eyed at this scene has clearly underdeveloped emotions).

Throughout the Church’s history, however, suicide has been considered a sinful act, no different than any other murder. Traditionally it was thought that suicides were outside the hope of redemption, for the last act of the suicide victim was his or her own murder– in Catholic theology, a mortal sin.

Without going into a long commentary here, or speculating about the final destination of suicide victims, I will only say that the movie does an excellent job of depicting both the genuine torment of Kerry and Mike’s souls, allowing us to sympathize with their sufferings, as well as showing the devastation each suicide caused in the lives of their loved ones. The heaven-like destination and the reunion of the brothers portrays that which we all naturally hope for, to be sure. The scene is powerful in depicting the goodness of life, and our natural longing for eternal life and reunion with loved ones. However, how Kerry and Mike’s deaths affected those still alive is not underplayed. Maura Tierney’s performance of the mother, Doris von Erich, spotlights the pain survivors are left to endure. One even has the sense that had Mike not first fallen into the temptation of self-murder that Kerry may not have either. And so, The Iron Claw, is successful in this regard as well: neither glorifying suicide, as some recent films have tried to do, yet also not leaving us cold as to a genuine hope for its victims.