In a previous post, I explored an interpretive option as to why Moses was prevented from entering the promised land. It is an interpretation often overlooked by pastors. There I argued, based off of Jewish exegesis, that God punished Moses because Moses, at the Rock of Meribah (Exod 17; Num 20), presented himself and Aaron as the source of divine power, not Yahweh, and in doing so not only elevated himself in the eyes of the Israelites but also demoted God in the eyes of the sons of Jacob. One concern that motivated that post was the sense many skeptics have regarding God’s character, especially in the Old Testament. This skepticism about God’s moral compass, as presented in the Hebrew Bible, is not new. It goes back to one of the Church’s earliest heretics, Marcion, who I have written about here. One reason for this skepticism is that the God of the Old Testament, Yahweh, seems to acts arbitrarily and without good reasons when it comes to divine punishment. As such, curses and punishments that human beings incur seem unwarranted, even cruel. This post will address another of these difficult passages: the curse of Canaan (Ham’s son).

The Incident Between Ham and Noah

The passage in view is a hard one, it is found in the book of Genesis, and has to do with a bizarre incident that takes place after Noah and his family are rescued from the flood. It begins with a mention of Noah being the first viticulturist and, as a result, the first to get drunk after the deluge.

18 The sons of Noah who went out of the ark were Shem, Ham, and Japheth. Ham was the father of Canaan. 19 These three were the sons of Noah, and from these the whole earth was peopled.

20 Noah, a man of the soil, was the first to plant a vineyard. 21 He drank some of the wine and became drunk, and he lay uncovered in his tent. 22 And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father and told his two brothers outside. 23 Then Shem and Japheth took a garment, laid it on both their shoulders, and walked backward and covered the nakedness of their father; their faces were turned away, and they did not see their father’s nakedness. 24 When Noah awoke from his wine and knew what his youngest son had done to him, 25 he said,

“Cursed be Canaan;

lowest of slaves shall he be to his brothers.”26 He also said,

“Blessed by the Lord my God be Shem,

and let Canaan be his slave.

27 May God make space for Japheth,[c]

and let him live in the tents of Shem,

and let Canaan be his slave.”

In this section, we see that Canaan, the son of Ham, is cursed by Noah with a rather severe curse. He is to be “the lowest of slaves” and a perpetual “slave” to the posterity of Ham’s brothers, Shem and Japheth, who, unlike Ham, acted quite differently vis-a-vis their drunken, naked father. At face value, it would seem that Noah calls down a divine curse upon his son for merely “seeing” his father naked. If that is all that there is to this case, the skeptics may be right about God’s moral character. For to punish an entire family line in perpetuity simply because some forebear saw their father naked seems both arbitrary and callous. But, is that all there is to the story?

Did Ham Rape Noah?

In his rigorous treatment of homosexuality in the Bible, The Bible and Homosexual Practice, New Testament scholar Robert Gagnon gives a brief history of the exegetical tradition behind Genesis 9:20-27. He admits that at first glance, the text seems merely to suggest that Ham “saw” Noah’s naked state. Nothing more is explicitly said about Ham’s actions than that. However, if Ham is punished merely for “seeing” his father’s nudity, then some early cultural tradition exists about which we know nothing, namely, that seeing one’s father naked warrants his curse. This would be truly esoteric.

However, if we assume that perhaps Ham’s actions included more than just seeing Noah naked, many problems start to clear up, most poignantly why Noah’s curse upon Ham’s son was so severe. It should also be noted that even if we suspect that Ham had immoral intentions, to go along with his visually seeing his father, this might not be sufficient for such a punishment. God’s punishments, or curses, usually relate to immoral or iniquitous acts. That is not to say intentions don’t matter, and certainly Noah’s curse could relate merely to Ham’s seeing and having bad intentions. However, that itself is speculative, since nothing is said about Ham’s inner mental states, nor is anything revealed to us about how Noah would have known Ham’s intentions. After all, this is not God cursing Ham directly, it is Noah who invokes the curse.

Donald J. Wold summarizes both problems: that of an unknown, esoteric custom and of immoral intent:

Perhaps Ham saw his naked father and entertained lewd thoughts (i.e., lusted after him), but did nothing about it. If so, this incident would be one of the earliest examples where an individual is made liable to a curse or penalty for merely intending to do something….Scholars who accept the literal view maintain that Ham only saw his nude father, but they must defend a custom about which we know nothing. They must also presume an immoral intention based on the severity of the curse imposed by Noah.

quoted in Gagnon, The Bible and Homosexual Practice, 64

Gagnon, following other scholars like Wold and Martti Nissinen, goes on to list six reasons why Ham may not have merely looked at his drunken father, but actually took advantage of him sexually:

- The story has Ham inside the tent, meaning that he was already there while his father was drunk and naked

- The text implies that when Noah awoke he claims Ham had “done” something to him; merely seeing someone doesn’t seem to warrant the claim that something was “done” to them. Moreover, as O. Palmer Robertson points out:

It seems very unlikely that Noah would have had any remembrance of a mere look from his son while he was in a state of drunkenness.

quoted in Gagnon, Homosexual Practice, 65 fn.65

- In other sections of the Hebrew Bible (Lev 18:6-18; 20:11; 17-21; 18:19) “the language of ‘uncovering’ and ‘seeing the nakedness of’ connects up with similar phrases denoting sexual intercourse.” (Gagnon, 66).

- In the ancient Mesopotamian context, homosexual rape is presented as a means for one man to usurp the power of another. By “feminizing” the patriarch in this way, Ham lays claim to the headship of the family.

- Ham’s brothers, Shem and Japheth, do the opposite of Ham; taking “great pains not to look at their father” (Gagnon, 67) and covering up his nakedness. Their pious act is meant to contrast with Ham’s wicked one.

- Finally, and most poignantly, homosexual, incestuous rape would explain the severity of Noah’s curse upon Ham’s progeny, and, match up with why it is Canaan who is cursed and not Ham alone. For in Ham’s misuse of his “seed” (his semen) it is his seed (progeny) that is cursed. For more on the importance of semen in Old Testament thought, see here.

This final point also has an etiological purpose, meaning, it gives a mytho-historical account of why the Israelites are justified in their later conquest of the land:

The Canaanites deserve to be dispossessed of the land and made slaves because they are, and always have been, avid practitioners of immoral activity. In the new post-diluvian world, it was their ancestor that committed the most heinous act imaginable–not just rape, but incest; not just incestuous rape, but homosexual intercourse; not just incestuous, homosexual rape, but rape of one’s own father, to whom supreme honor and obedience is owed. It is, in effect, in the Canaanites’ blood to be unremittingly evil.

Gagnon, 67

Gagnon, Wold and Nissinen are not alone in suggesting this “incestuous, homosexual rape” view of Ham’s sin, as opposed to the other view that Ham merely “seeing” Noah was sufficient to warrant the curse. Gagnon refers to several other scholars who have argued in similar fashion, to include such Old Testament figureheads like Gerhard von Rad, Nahum Sarna, Herman Gunkel, Seth Daniel Kunin, and others.

For example, according to Sarna:

The earliest post biblical traditions take the verse ‘literally,’ and the final clause of verse 23 would seem to support it. Ham compounded his lack of modesty and filial respect by leaving his father uncovered and by shamelessly bruiting about what he had seen. On the other hand, the verbs of verse 24 and the severity of Noah’s reaction suggest that the Torah has suppressed the sordid details of some repugnant act. Rabbinic sources are divided on whether Ham castrated his father or committed sodomy.

Nahum Sarna, JPS Torah Commentary on Genesis, 66 [emphasis added]

That said, we should also point out, that even if ‘the earliest post biblical traditions take the verse literally,” not all of them did. Gagnon shows that there were some early interpretations, both Greek (Aquila, Symmachus and Theodotian) and Jewish (Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 70a), that believed either Ham had raped Noah, or castrated him.

My aim here is not to make a definitive exegetical claim. That is beyond my capacity as a layman with regard to biblical exegesis. However, it seems worth pointing out that if this interpretation of Genesis 9:20-27 really is a live option in the pool of exegetical views, then why do we never hear it mentioned from the pulpit?

Three Speculations About Not Preaching on Noah’s Rape

These are speculations, to be sure. I have no empirical data or studies to back them up. However, I have a strong suspicion that these are at least three reasons why this interpretation of Genesis 9:20-27 is almost never brought up in church (also, if you are at a church where it has been, please comment below; I would love to hear about it).

First, many Evangelical Pastors are biblically unlearned, or undereducated, especially when it comes to the Old Testament. This is hard for me to say, because I consider myself a low-church Evangelical (after being raised in a very high Roman Catholic tradition). Nevertheless, there is a problem with unlearned exegesis, exegesis of the Bible that doesn’t take into account rigorous study of the languages, the background context (historical and cultural) as well as intertextuality. That said, this is especially a problem when it comes to the Old Testament; it is somewhat less so with the New. That may be understandable, given our focus is on Christ, but there is still a desperate need in American Evangelicalism of recovering a robust sense of what one scholar (John Goldingay) appropriately called “The First Testament.” Before he died, Michael S. Heiser, was doing an excellent work in reorienting pastors and church ministers to the First Testament. This work must continue.

Second, there is the cultural pressure. After all, who wants to preach about the problem of homosexual sexual intercourse in today’s climate? The amount of online hate one would receive is daunting. One can get in real trouble these days for going against the cultural narrative, although, there may be some evidence the tide is shifting. Still, one has to ask oneself as a minister of God’s Word: “since when is the approval of man, or the fear of disapproval, more important than the truthful articulation of the Word of God?” Doesn’t one?

Finally, and this may be a very legitimate reason to not bring up the “incestuous, homosexual rape” view, is the simple indecency of the subject. According to many critical scholars, the depravity of the act may have been the very cause of the story being truncated, and, as such, ambiguous:

The section deals with Noah as a culture hero who introduced viticulture and who fell victim to his progeny’s depravity. Because the original incidents, in all their detail, were well known to the biblical audience and for reasons of delicate sensibility, only the barest outline of his downfall is reported here. The fuller account, now lost, has been truncated and condensed, resulting in many difficulties we know find in the narrative. For instance, we are not certain if Ham is guilty solely of voyeurism or if the description of his offense in verse 22 is a euphemism for some act of gross indecency.

Sarna, JPS Commentary Genesis, 63-64

However, if it is the case that later scribes redacted the story so as to eliminate its most unsavory parts, they could do that in good conscience, knowing that there audience took for granted the sinful, God-dishonoring nature of homosexual and incestuous sex. Today, however, that assumption is hardly clear. This would seem to warrant a more well-rounded exposition of the text, to include the view that Ham’s sin was something far worse than a mere, lustful glance.

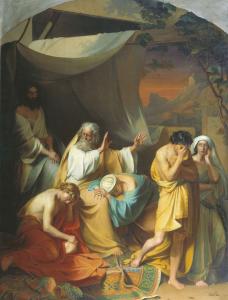

featured image: Ксенофонтов Иван Степанович. Ksenofóntov Iván Stepánovich (1817-1875), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons