I sometimes hear people say that a traditional sexual ethic, which  believes that God prohibits same-sex sexual relations, is intrinsically harmful. The ethic itself leads to homelessness, isolation, and increases the suicide rate among gay teens. Much of the criticism I’ve received for my work on LGBTQ related questions do not use these arguments, but I have seen it come up from time to time. Strangely, I’ve received similar criticism from conservative Christians who think my endorsement of the phrase “gay Christian” will end up harming gay teens who need to see that their identity is in Christ and not in their sexuality. (As I argue in my book, this distinction is a terrible false dichotomy.)

believes that God prohibits same-sex sexual relations, is intrinsically harmful. The ethic itself leads to homelessness, isolation, and increases the suicide rate among gay teens. Much of the criticism I’ve received for my work on LGBTQ related questions do not use these arguments, but I have seen it come up from time to time. Strangely, I’ve received similar criticism from conservative Christians who think my endorsement of the phrase “gay Christian” will end up harming gay teens who need to see that their identity is in Christ and not in their sexuality. (As I argue in my book, this distinction is a terrible false dichotomy.)

I must say that I’m getting used to the so-called “harm” argument. People say that my leanings toward an annihilation view of hell is producing harm among unbelievers, who need to know about the real horror of eternal conscious torment so that they can turn and be saved. Non-pacifists say that my views on violence will lead to more deaths among innocent people, since fewer people will be defending their families and their countries.

It’s easy to say that one’s ethical views are causing harm, yet it’s much harder to prove it, of course. It takes a good deal of psychological and sociological work to pin-point the exact cause of such harm. Life is much more complicated than my “harm” theorists would have it. What I find most odd about the “harm” argument is that it doesn’t match the myriad of testimonies I’ve heard from LGBTQ people themselves.

Bear with me for an anecdotal moment. Almost every LGBTQ person I’ve talked to describes their experience with Christians and the Christian church in frightful terms. They were isolated. Physically assaulted. They were dehumanized. Kicked out of their homes. Mocked. Shunned. Made fun of over, and over, and over. I would guess that at least 90% of the LGBTQ people I’ve talked to have had some horrible experience with the church and were treated like some sub-species of the human race.

Hearing story after story has been one of the most disheartening and maddening things I’ve ever experienced as a Christian. But is this horrible abuse really intrinsic to a traditional sexual ethic? Or is it a direct byproduct of a legalistic, sinful, fear-driven, ungodly posture that hasn’t been bathed in the scandalous grace of the gospel? If a gay teen comes out and is met with aggressive love, life-long friendship, and is embraced and valued and hugged and kissed and surrounded with a committed community eager to walk with her day and night as she’s wrestling with her faith and sexuality—will she still feel persecuted and dehumanized and harmed by the traditional ethic of her friends?

What we are experiencing is a posture problem, friends. Not a theological one.

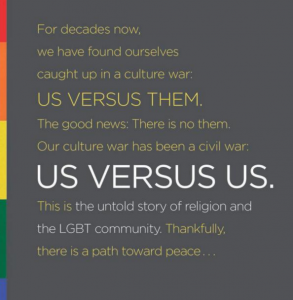

This is all anecdotal, of course, which is why Andrew Marin’s new book Us vs. Us is so important. Us vs. Us contains the largest scientific study ever done on the faith background of the LGBTQ community,  and proves that most LGBTQ people do not see the evangelical church’s position on sexual ethics to be the cause of the harm they’ve experienced in church. In fact, according to Marin’s study, the majority of LGBTQ people who have left the church desire to come back as long as the church changes a few things. But changes in theology were shockingly low on the list of things they desired to change. Most of the problems that LGBTQ people had with the church are relational not intrinsically theological.

and proves that most LGBTQ people do not see the evangelical church’s position on sexual ethics to be the cause of the harm they’ve experienced in church. In fact, according to Marin’s study, the majority of LGBTQ people who have left the church desire to come back as long as the church changes a few things. But changes in theology were shockingly low on the list of things they desired to change. Most of the problems that LGBTQ people had with the church are relational not intrinsically theological.

Here are some findings:

– about 86% of LGBTQ people were raised in a religious community; about 83% of which were raised in a Christian faith context.

– 54% of LGBT people leave their religious community after the age of 18

It’s here were some people want to say, “Yes, exactly, they left because the church’s sexual ethic is harmful.” But actually, only 15% of LGBTQ peole left the church because of “theological interpretations of sin” (that is, different views on sexuality).

If you’ve bought into the “traditional theology is harmful” argument, you’d think it would be like 80-90%. The fact is, most LGBTQ people have left the church for relational not theological reasons, such as: They did not feel safe (18%), they experienced a relational disconnect with leaders (14%), Christians were unwilling to dialogue (12%), or they were kicked out of the church for being gay (9%). I agree with Marin, who sums up these findings:

The dominant cultural narrative from both camps suggests that LGBT people leave most frequently because of a theological disagreement on sexual ethics and same-sex marriage. From an LGBT perspective, religious factions induce shame through teachings on sin and social oppression through theological interpretation. From a more religious-conservative perspective, LGBT people can’t handle God’s truth on relationships and sex. Our data however, runs counter to both these dominant narratives.

Now, at 15%, “different interpretations of sin” sill ranks #2 on the list of reasons. It’s not insigifcant. But at 15%, one could hardly make the case—based on evidence not just rhetoric—that a traditional sexual ethic is intrinsically destructive. Most LGBTQ don’t see it that way.

Marin also spends a good deal of time looking at what would bring the dechurched LGBTQ people back to the faith. Strikingly, 76% of the LGBTQ people who left the church said they would be interested in coming back. But what would the church need to change for them to come back? Again, some affirming people I know would throw up their hands and say, “well, the destructive non-affirming theology would need to change, of course!” I think I was even more shocked at the response Marin got:

Eight percent.

Only 8% of LGBTQ people (of the 76% who expressed a desire to return) said that the church would need to change their theology for them to return. Other reasons include: Feeling loved (12%), given time (9%), no attempts to change their sexual orientation (6%), authenticity (5%), and support of family and friends (4%). As Marin says: “implicit in that statistic is that the other 92 percent would be open to return even without that faith community changing their theology.”

What we have on our hands, friends, is a posture problem. Many Christians have been so busy spouting off their stance on homosexuality that they’ve missed the actual people in their midst. Changing your posture does not require a shift in theology. After all, theology is not about our religious thoughts about God, but God’s revelation to us.

Andrew Marin shares many LGBTQ testimonies in the book that embody the results of his study. These thoughts from Tasha, a 21-year-old lesbian living in Miami, capture it well:

“All I wanted was to feel loved by those in the church I grew up with. To me love is not being demanded to turn straight or loving me “in Truth.” The only truth I ever got wasn’t in love. It was done by those who thought they had the right to tell me how wrong I am and how disappointing I am to God. That’s not love. Love is giving me time to be with you to figure this out together. If you let any church people read this, tell them that I don’t have to be right to feel loved. I have to be dignified in our disagreement.”

Christians don’t need to change their theology. But we do need to change our posture for the sake of the gospel. People, all people, need to know that they are valued by their Creator, who’s on an aggressive mission to love humanity out of the grave and into his bountiful garden.

Posture shift, folks. It’s vital to our theology. Because how you belief is just as important as what you believe.