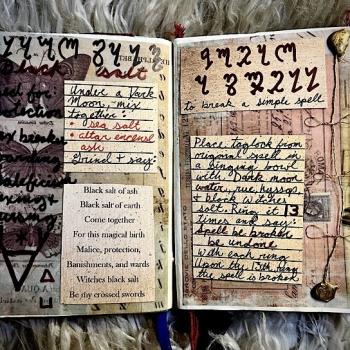

Over on Gone Witching, K.C. Alexander recently posted an exploration of what it means to be “chosen” by the gods, especially those gods who might bestow talent for practicing magic. But being chosen is not the only path to practicing magic. Some are chosen. Some begin by devoting themselves to the art. And while we talk openly of these two ways to begin our work, there is also a hidden path.

How we find the path is an interesting avenue of exploration. Living in a world that looks at magic with equal portions of disbelief, disdain, terror, and a lust for power, we spend little time really delving into why people study magic, how they get there, and whether they would rather be off playing mini-golf.(1)

This question is one with which we all have to wrestle as we seek our own places in the world. I struggled with this question for decades. Though we don’t talk much about it, there are generally two ways to arrive in magic-land. The first is to be “called” – to have a vocation.(2) The second is to pledge oneself to the work, or as some might say, to have devotion.(3)

Vocation and Devotion

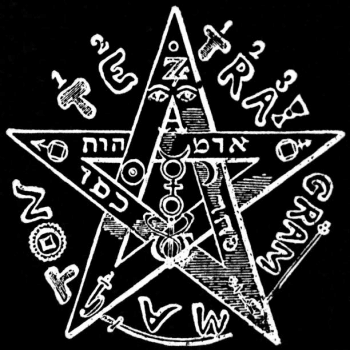

It is pretty clear that vocation and devotion, as terms for paths into magic, have religious connotations. Whether we are called or bind ourselves to the path to the divine, these are the words we use to talk about it. That goes back at least as far as our Christian heritage.(4)

Yet, neither of these things, vocation or devotion, need be explicitly religious. At least since the mid-16th century, people have been talking about their careers as “vocations.” And going back to the Romans, “devotion” is about pledged loyalty – I suspect originally sworn before the gods, and not to them.

These are the two common paths for learning magic. Where I understand that K.C. and many other struggle is the idea that vocation is somehow the higher path. It is a bias we inherited from our Christian forebears – that direct communion with God or the gods requires the other to initiate that relationship. Such an attitude is, if you’ll pardon my frankness, crap.

Culturally, we prefer “vocation” because it confers immediate legitimacy. With little common understanding of the long process of spiritual maturation, we naively believe that such a calling somehow makes it harder to stray. The West has a long history is being super-afraid of spiritual charlatans, though we seem to accept snake-oil salesmen of every other stripe.

The crux of the problem is that our concept of spirituality is religious by habit. For a variety of culturally significant reasons, we value the transformative religious experience over others. There are only a few ways that Westerners can claim that something is “authentic” – and religion is the big one.

It’s not that we believe everything, or even anything, that a religious person says. But we believe that they believe it, and that makes “religion” a protected class of thought. Being “godtouched” thus protects the person making the claim.

But culture doesn’t mean much when it comes down to connecting with the sacred. Culture is our starting point; it shapes who we are and flavors our experience, but it is not the point. The point is rather to transcend our everyday, culturally-accepted self and reach for something more.

Spiritually speaking, it is entirely possible to become a magician through devotion to that purpose. Single-minded pursuit of such a goal might not guarantee success, but it is certainly a worthy path.

Magicians, Priests, and the Hidden Path

With that said, I wanted to lay out some thoughts, concepts, and a model for understanding how we grow into being practitioners of magic.(5) Being chosen is one of the three ways to get there.

Without getting into the metaphysics of it all, we can liken spiritual awakening to a baby chick coming out of an egg. Like the chick, we suddenly see a whole world that we had never seen before. And, like the chick, that world is a lot larger than what we initially perceive.

The devotional path to learning magic, the path of the magician, is one where significant work needs to be put in before we ever see outside of ourselves. Magicians open themselves up to a greater world through practice. If we imagine the magician as a chick leaving an egg, these are the little buggers who peck at the shell from the inside until they are big enough and strong enough to emerge more or less on their own.

The magician, then, comes into the world of magic at long last, fully formed and as prepared as anyone can be. If the magician has a guide, it is usually another person who has walked that path themselves.

Those who are called to magic, we might call priests. These priests are like chicks who, while trying to break free of their egg, have an outside force hear their struggles and offer some assistance cracking the shell. The chick analogy seems especially apt, as the newly “born” imprints on the “helper” in a big way — breaking away from such a bond (or binding) is as intense as getting over a bad parent.

The newly awakened priest is nowhere as self-sufficient as the magician. The awakening comes before the hard work, not after. Yet the path to becoming complete is no shorter for it.

![Jacob's Ladder - William Blake [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/928/2018/04/Blake_jacobsladder-805x1024.jpg)

These shamans are like chicks who have their shell broken accidentally by trauma in life. Most of them die. Many of the rest are never quite right. In the West, those who manage to survive often end up trying to follow one of the other two paths. But this is also how we get a lot of natural psychics, healers, sensitives, and the like.(7)

This typology is a natural extension of understanding the process by which one becomes a practitioner. However, like most things in life, it’s neither only one or the other. In practice there is a fair amount of overlap.

What happens when someone trains for years as a magician, but then calls upon the assistance of an outside power to make the final push? How about the child offered to their gods, but who then breaks away to becomes more self-sufficient? Or (super common) the shaman who trains on one of the other paths?

The important thing to remember is that each of these is a way of starting. A complete person, awakened in body and spirit and with access to the world of the sacred, could start in any of these three ways. Sure, the way you get there will shape how you see it. Followed to its end, each of these paths leads to the same end: a person living fully in the everyday world and yet unified with the divine.

(1) Don’t get me wrong. Studying magic can be rewarding, but it will only circuitously address anything toward the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Magic does not come with a steady paycheck, stability, or social status. Bluntly, we have to plumb the deeper nature of the universe and ourselves on our own time and our own dime.

(2) Vocation, in this sense, originally did have a religious meaning. Around the time of the Protestant Reformation (1517 – 1648), it changed to mean any purpose to which one felt called. Effectively, as the reins of Western religion slipped from the Catholic Church’s hands, people began to find themselves called not just to priesthood, but to all sorts of roles in life. It can refer to everything from a full-blown vision from the world of the sacred down to following in the footsteps of a parent.

(3) Devotion comes from a Latin root that more or less means taking a sacred vow or a pledge of loyalty. Through the Christian tradition, this came to refer more-or-less exclusively to pledges to God. It then moved back toward the original meaning, where we might talk of a “devoted” husband or employee.

(4) In order to be a Christian priest, it is fairly common to have to be able to prove one’s vocation through the process of discernment. And they do not mean it metaphorically – in the Christian world, such a calling is a serious matter. And while we aren’t Christian, Christianity has influenced just about ever aspect of Western culture for about two millennia.

(5) The word “shaman” as used in the West covers a lot of territory. Used in various contexts, it can refer to any of the three types I have outlined. Though the word originally used to denote a specific cultural type of practitioner among the Buryat and related groups, it has taken on a meaning and life of its own in the West.

(6) To get a real sense of the breadth of this category, we only need to think about all those who have Near Death Experiences, or walk away from car accidents and other traumas with an extra sense. Sometimes, the trauma itself can lead to awakening.

(7) It’s worth noting that there are traditions of magic that utilize this type of initiation. From ayahuasca ceremonies to vision quests, teachers may created relatively controlled traumas in order to help their students reach the sacred. I would categorize such people as magicians rather than shamans.