They say that patience is a virtue. We imagine, then, that it is something we are born with. And to a certain extent, that is true. Some people just are born with a high level of patience. For the rest of us, it is something that we have to cultivate.

Now, if you want to live your life just like everyone else, herded this way and that, then you will have little need for patience. Quite the opposite! The person who follows the crowd with the least hesitation will always be seen as a leader.

But if you want to do something different? To become more than you ever thought you could be, or to make a difference in the world? You will need patience. It is not the only virtue, but it is a good place to start.

Understanding Patience

In everyday language, patience is about holding back and not doing something right now. While we talk a good game, it is not a virtue that we train regularly.

From advertising to group-think to competition for resources, our whole life screams at us to act quickly. But the self-restraint that patience entails is actually a way to empower ourselves.

Further, patience isn’t only about holding back. In a larger sense, by growing this characteristic inside yourself, you will be able to act in accord with your context. Beyond the basics, patience is not about moving slowly, but more so about being “in tune” with your situation, whatever it is.

Patience, when we examine it deeply, hinges on the ability to see past our reflected self and interact with the actual world rather than our presupposed map of it. That is why it is so hard to develop.

Going Along to Get Along

Most people, on most days, can hardly see the world beyond their noses. This is not a judgement against them, but rather a recognition of how all of us are required to censor our own perceptions in order to function in our extremely dense social environments.

Humans evolved to work together in small kin groups that anthropologists term “bands.” These extended family groups generally have less than a hundred members and no fixed residence.

In an evolutionary sense, people today live in environments to which we are very poorly adapted. And that means that we need to turn off huge portions of our instincts just to get along. Most of our extended awareness, from intuition to instinct, has to be dulled, blunted, or broken.

We accomplish this blunting in various ways. On a physical level, we wash ourselves pretty thoroughly, wear perfumes and deodorants, and cover ourselves with clothes. That pattern is the most obvious one.

There are mental parallels. We avoid certain topics, think only in allowable ways, and keep our thoughts running in safe circles.

Spiritually, we build a barrier out of our identity as a filter. It blocks most of the information coming from the outside. It is how we maintain our individuality.

For most people, every time we try to look outside of ourselves all we see is the inside of that barrier. We see only our own filter, not the whole of things.

The Reflected Self

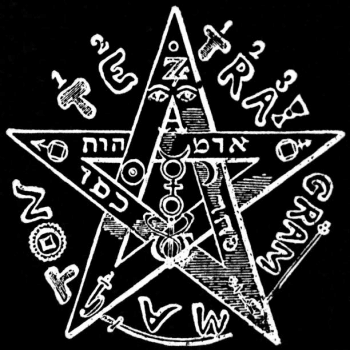

We cannot see beyond the bubble of the reflected self. In order to see the world as itself, we have to break this barrier, this identity. That is, in fact, the meaning of crossing the abyss.

The bubble of perception is a spiritual shell that encases people(1). Now, there are some who would say that the bubble of the reflected self is “just” a metaphor. From an everyday perspective, that is operationally true. If, for you, the “world of the spirit” is a metaphor, then these practices will also hinge on that same metaphor.

In my experience, as someone who has crossed the three abysses and lived to tell the tale, the everyday world from before we cross the abyss is in fact just as much a metaphor as all the rest. It is just the shared and preferred one — and there is value in that.

But if we want to understand things more deeply, we will need to move in directions that do not exist within the everyday world.

True Patience

Patience, then, is not simple self-restraint. It is part of a much larger process of beginning to align your perceptions with the outside world.

True patience relies on awareness of whatever situation we find ourselves in. For it to be effective, we need to have clear perceptions of the world around us. Beyond that, we also need the self-control to align ourselves with that situation.

The point here is that patience is not about waiting. Patience is, instead, about understanding the larger context and acting in according with it. Patience is about finding the correct timing and acting in accordance with the fundamental ground.

In other words, patience is not about sitting around and doing nothing. It is about restraint, awareness, control, and timing.

Developing Patience

If you are a naturally patient person, all you need to do in order to develop patience is practice. But for those of us not blessed with this virtue in abundance (and I am totally including myself, here), it is useful to have a deeper understanding of its components. These are restraint, understanding, control, and timing.

Restraint

The first skill in developing patience is restraint, or learning how to not-act. It is harder than it sounds. To do this we have to teach ourselves to step back and say, “I am going to do nothing.” This is not the non-action of the lazy, but instead a watchful non-action that seeks deeper understanding.

If we think of this in terms of archery, restraint is the willingness to admit that it is not shooting alone, but hitting the target, that is the whole point. When we first get started, we are eager. We feel like loosing the arrow is enough. We imagine that with infinite shots, we will eventually make our mark. But restraint means shooting when we are ready to succeed.

Understanding

The more we can grasp about any situation, the better we will be able to integrate successfully with it. Understanding might start with knowledge, but it goes further than what can be conveyed in words. To get past the limits of language, we need to gain experience with the thing we seek to understand.

To develop an understanding of understanding, find any skill that interests you and develop master in it. It does not matter if this is a martial art, flower arranging, a musical instrument, or anything else. All that matters is that, in a single area of endeavor, you come to understand what truly “deep” knowledge is.

Again, in terms of archery, this means more than knowing how to shoot. It means understanding the quality of the bow, the straightness of this particular arrow, the speed of the wind, the humidity in the air, your mood, your target’s behavior (assuming you want to shoot something more than a piece of paper!), and all of the infinite details that might affect your shot.

Control

To balance out restraint, we need to develop controlled action. Having perfect understanding is not enough. There needs to be flawless execution as well. This is where practice comes in. In my experience, it is only through repetition that we can really understand something.

Once we have an understanding of something, we develop control by being able to act on what we know. The world is a messy place, and while we might imagine the perfect performance of any skill, there are a million factors to take into account to achieve perfect timing.

Loosing an arrow is the simplest thing. Knowing what will happen when you do is so much harder.

Timing

When we can restrain ourselves from acting rashly, understand the gestalt of the situation, and have the control to fit our own actions into the environment, we can achieve perfect timing.

The loosed arrow leaves the bow but remains part of us. This is the final result of patience.

Notes

(1) They also encase not-people, perhaps, but that is a discussion for another time.