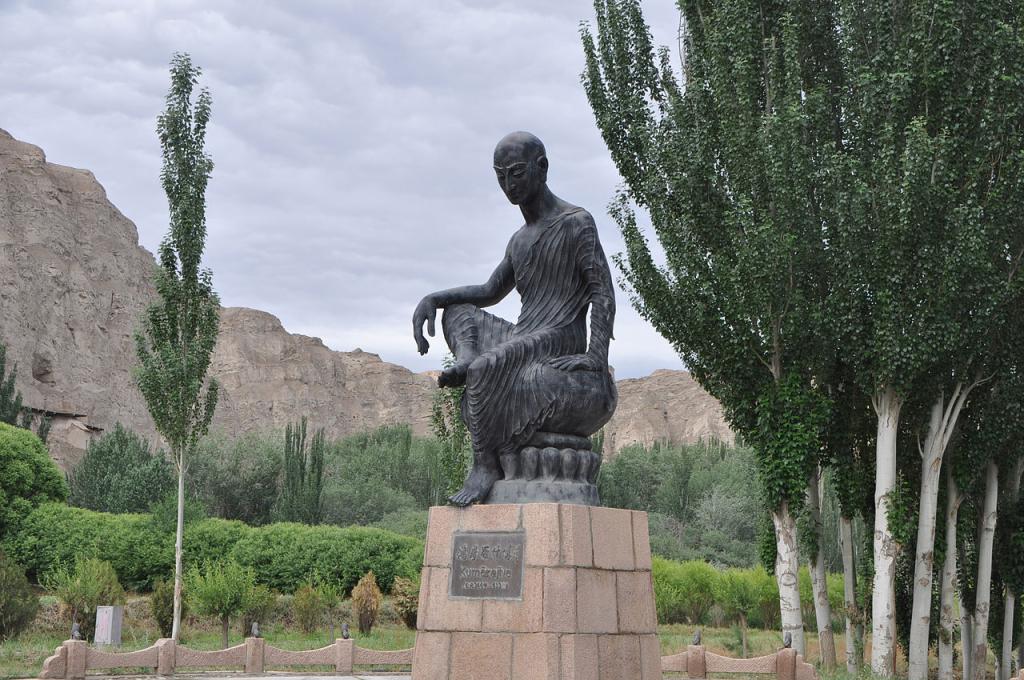

Kumarajiva (344–413 CE) is remembered for translating many significant Buddhist scriptures from Sanskrit into Chinese. His influence on the development of Buddhism in China cannot be overstated. And he accomplished this while being caught up in outrageous political upheavals and intrigues in China.

For example, Kumarajiva spent several years of his life as the hostage of a rogue warlord. But in order to appreciate what Kumarajiva went through, you need a bit of background into China’s history.

Big Troubles In China

During Kumarajiva’s lifetime China was not a unified country. When the Han Dynasty ended in 220 CE, China fractured into many small kingdoms. The space of time from 220 to 589 CE is called the “Six Dynasties” period, because southern China was ruled by six short-lived, successive dynasties.

But the situation in northern China, where our story takes place, was more chaotic. In about the year 300, nomadic tribes from the west and north invaded northern China and split it up among themselves. In the period from 304 to 439, sixteen dynasties rose and fell in north China.

Buddhism Comes from the West

Buddhism had been introduced to China in the 1st century CE, mostly by monks from central Asia who followed Silk Road merchants eastward into north China. (See “The Edicts of Ashoka” for more on how Buddhism spread from India to central Asia.)

And this brings us to Kumarajiva, who was from Kucha. Kucha (now Kuqa) was an ancient city-state that is in today’s southwest China, Aksu Prefecture. In much earlier times it was an oasis on the Silk Road, and in Kumarajiva’s day it was a place where the cultures of China, India, and central Asia mingled. And it was also predominantly Buddhist.

Kumarajiva’s father was a Buddhist scholar from India, and his mother was said to be from Kuchan nobility. He was given a rigorous education in Buddhist texts from early childhood. He received Buddhist monk ordination at the age of 20.

Kumarajiva Becomes a Hostage

Fu Jian (337–385), ruled one of the sixteen dynasties of north China, the Former Qin Dynasty. His capital was Chang’an, which today is called Xi’an, Shaanxi Province. Fu Jian was a great supporter of Buddhism. Among other things, he sent the first Buddhist missionaries into the Korean Peninsula to establish Buddhism there. However, Fu Jian also wanted to unify north China under his rule, and he launched a lot of attacks on the other dynasties to accomplish that. North China was not a peaceful place.

In about 382, Fu Jian sent his general Lü Guang with a large army to subdue the region around Kucha. He also told Lü Guang to escort the renowned monk Kumarajiva safely back to Chang’an. Note that the distance between Kucha/Kuqa and Chang’an/Xi’an is 1,484 air miles, or 2,389 kilometers, so this was a significant undertaking.

Lü Guang’s campaign in the far west eventually would succeed, but not before Fu Jian suffered serious military setbacks and, in 385, was assasinated by a rival. Former Qin itself would end in 394.

Kumarajiva’s Captivity

Lü Guang had an army but no lord to report to. So he took over some territory in northwest China and declared himself an emperor and founder of what scholars would call the Later Liang Dynasty. Kumarajiva would be his prisoner for a total of sixteen years.

Why Lü Guang kept Kumarajiva captive is not clear, as Lü was not known to be interested in Buddhism. It’s possible he thought that since Kumarajiva was some kind of holy man, his presence would ward off evil spirits.

It’s also not known with any certainty how Kumarajiva spent his days as Lü Guang’s prisoner. It’s believed he spent his time learning to read and write Chinese, which is certainly possible. There is a popular story that Lü Guang forced the celibate Kumaajiva to marry, but I suspect that’s a folk tale.

Kumarajiva Rescued

Kumarajiva was rescued in 401 after Yao Xing (366–416) of the Later Qin — which had replaced the Former Qin — ordered his armies to defeat Lü Guang and bring Kumarajiva to Chang’an. Kamarajiva spent the remaining years of his life not just translating, but also runnng a translation academy to teach younger scholars how to clearly render the subtle meanings in the Sanskrit texts into Chinese.

Much of Kumarajiva’s work focused on a school of Buddhist philosophy called Madhyamaka, which is foundational to the schools of Buddhism that would develop in China, Tibet, Japan, Korea, and elsewhere in east Asia. Through his translations, and through his many students, correspondents, and collaborators, he raised understanding of Madhyamaka far above what it had been before in China.

For those familiar with Buddhist scriptures — the roughtly thirty-five texts Kumarajiva gave to China include the Lotus Sutra, the Vimalakirti Sutra, the Diamond Sutra, and Nagarjuna’s Fundamental Verses on the Middle Way. In most cases Kumarajiva’s translation remains the canonical version in the Chinese Buddhist canon. The quality of Kumarajiva’s work remains relevant to this day. Many of the original texts are lost, and scholars still rely on Kumarajiva’s translations. A substantial portion of Mahayana sutras that are available in English were translated from Kumarajiva.

You can read more about the adventures of Buddhism in China in my book, The Circle of the Way: A Concise History of Zen from the Buddha to the Modern World (Shambhala, 2019).