When we say that Catholics don’t know the Bible, I am more and more convinced that the terms of the evaluation are inherently unfair. What Catholics actually don’t know is a specific way of knowing the Bible. We are also horribly educated, strained by confrontation with modernity, and needlessly factious. But all that doesn’t mean we don’t “know” the Bible.

It depends on what we mean by knowing.

This theory of mine is perhaps the result of being a cradle Catholic in theology, often surrounded by Protestants and by converts to Catholicism. In this context, I’ve been needled about my ignorance particularly often. I find it annoying. And I think that there is something real in my ignorance while there is also something deeply unfair in it.

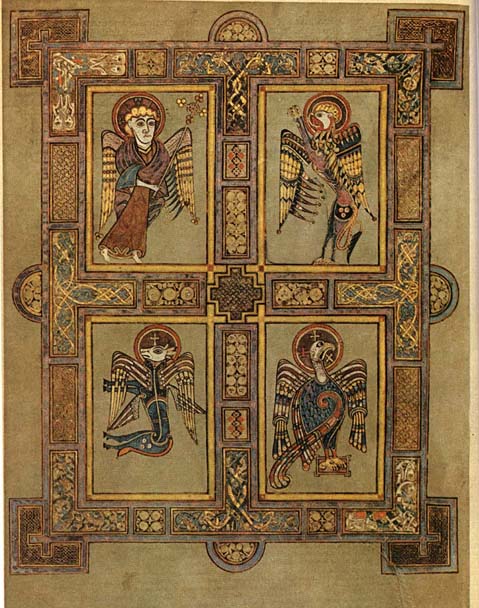

Catholics are terrible quoters of the Bible. This is in many ways a betrayal of our own past, as our greatest minds were essentially living concordances, able to flicker through phrases across the entirety of Scripture. It is also an artificial demand. Catholics are not asked to quote the Bible when they share faith together; they rarely come upon Scriptural quotations set aside from other forms of speech. They do quote the Bible all the time in various prayers and repetitions, with the quotations thoroughly stitched between ancient phrases, old wisdom, and physical movements. The biblical quotation might even be a half-quote or a paraphrase placed right next to others. These are all forms of biblical citation that, actually, more closely mimic great writings like those from Augustine or Irenaeus or others.

So, no, I don’t know “where” in the Bible that phrase comes from. And, yeah, that’s a problem. But when I’m asked for “where,” I am not only being asked to do something that doesn’t allow me to relate to the actual form of my own knowledge, but I am also being told – at least implicitly – that my form of knowledge is inferior. Is it, though? I’m not saying that Catholics shouldn’t learn context or read the Bible together, but I am saying that the other ways Catholics learn Scripture are good too.

I remember learning about some early 20th century intelligence tests done in Australia. They gave indigenous children the same test that they gave to white children, and the indigenous children did terribly. When a scholar adjusted the questions and cultural symbols to things that the native people actually used, however, their children were revealed to be as intelligent as anyone, and indeed to have a particular talent for spatial-directional thinking. Somehow I think that the question of knowing the Bible functions something like this among Catholics. The question is asked in a broadly Protestant way, and of course a Catholic doesn’t have the cultural symbols necessary to pass the test.

Catholic biblical knowledge is, in the first place, liturgically scripted. They have no idea they’re quoting the Bible most of the time, but they are, and “knowing” the Bible typically invalidates this type of knowledge before a Catholic even has the chance to realize what they’re saying. My Catholic students are instinctively drawn toward biblical phrases. They typically can’t even identify that these phrases are biblical, but they recognize them because they encounter them all the time. This is a kind of knowing.

It is a kind of knowing that allows for creativity that quotation-learning typically does not. I can combine phrases and concepts that may well horrify someone who wants to keep them discrete, but the cultural milieu of my own knowledge encourages these acts of creativity. Scripture can be paraphrased, and its images associated with one another. Is it out of context, or is the context Christological? Can we not say that it is often both at once?

My stubborn position is that Catholics know more Bible than they’re given credit for knowing, particularly because they know the Bible primarily through the saints. Hagiographies are strings of Scriptural quotations woven through someone’s life, imprinted in their legend. How can I not hear the Gospel telling me to give someone the shirt off my back and not also think of Martin of Tours? How can I not picture Saint Francis of Assisi in Eden? I learned the Gospel from these saints, and that doesn’t make it less Gospel.

I am always more upset when my Catholic students don’t know saint stories than I am when they’re clueless about the Bible. However many our profound faults, we as a people have always told stories of the saints. These were how the simplest of us learned how to act like a Christian, replete with holy wonders that make biblical history and our history appear as a seamless whole. Thérèse says that “all is grace,” and she taught me Paul. Christ makes the loaves and fishes multiply, and I can list the saints who lived on the Eucharist alone. Saints preached to the animals, and why wouldn’t they? Daniel stands with lions and Noah learns of land from a dove.

It is a thoroughly biblical way of thinking, albeit filtered through a wild tradition that treats the world around itself as equally as wild. The Bible is just as wild. And I want to honor it.

That doesn’t mean that I think it’s okay how most Catholics don’t have a clue about saints or Scripture, or that I think we shouldn’t learn quotations or take part in Bible studies. I just want those things to stand in harmony with our other gifts rather than standing against them.

And I don’t want to be told that I don’t know the Bible. As if it were that simple. It’s more complicated than that, and I could learn the Bible more easily if I were allowed to use the ways I really do know it already.

Plus I’m just cranky today. So back off.