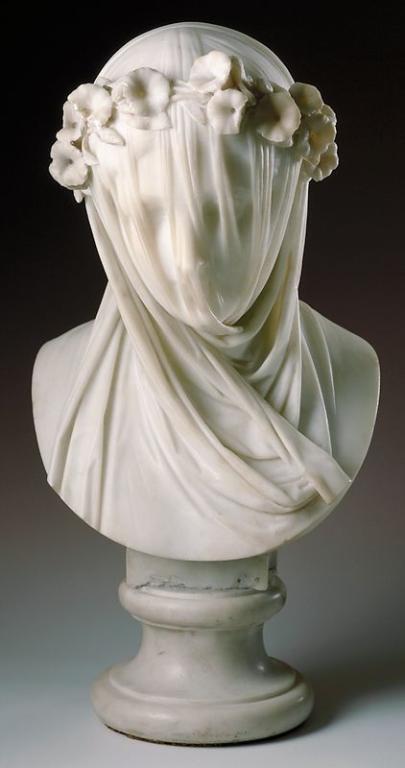

Now is the week when all the statues in churches are veiled. Crucifixes covered over. Saints look on only in outlines. I always imagine a stark moment in a ballet or a play, when a woman raises her shawl from her shoulders – stretching it wide like wings – and closes it over her head, grave in mourning. The silent collapse of what might have been.

I can’t fathom where I got the image. Something about Gregory of Nyssa’s commentary on the Song of Songs haunts my consciousness, but I have no copy with me. The Bride is covered by a veil (cf. 4:1-3, 6:7).

And this is a relief, since I hardly know how to stare down my own guilt and loss – they are not the same – without flinching. I don’t particularly want anyone to see. But this practice is more than a kind of privatization of shame (which by its nature isn’t private anyway). A veil is a surrender of control over meaning. This week, holy things are veiled as if to gesture toward their obscurity, by which I mean their immensity. This is the one week that the Church surrenders her images save the barest ones: hearing the words of Scripture, kissing a cross, washing feet. Even the tabernacles are emptied, and light itself flees the churches.

Isn’t it like G.M. Hopkins says? He describes the cry – the prayer – of that nun lashed to the mast of the Deutschland with her sisters as it sinks in a terrible storm.

Ah, touched in your bower of boneAre you! turned for an exquisite smart,Have you! make words break from me here all alone,Do you!—mother of being in me, heart.O unteachably after evil, but uttering truth,Why, tears! is it? tears; such a melting, a madrigal start!Never-eldering revel and river of youth,What can it be, this glee? the good you have there of your own?

Ground of being, and granite of it: past allGrasp God, throned behindDeath with a sovereignty that heeds but hides, bodes but abides;

…

Our passion-plungèd giant risen,The Christ of the Father compassionate, fetched in the storm of his strides.

It is something like this. A touch to bone or a welling from the deep, and the Church allows the enormity to be at times speechless and sightless, to be as naked as He was. Rilke says in his Duino Elegies, “Wer saß nicht bang vor seines Herzens Vorhang?” Who hasn’t sat afraid before the curtain of their heart?

For Gregory, the veil has to be removed. But the time for that hasn’t arrived. (It will in the flickering form of a single light. Then the whole Church wakens in a song.) And even then, true knowledge of God is a luminous dark.

Christians mourn strangely. The coffin is draped in purple or white, the first a sign of the cross that makes forgiveness possible and the second a sign of the resurrection. What a way to mourn: to call a death an immensity, to call death a sign of God’s compassion. A funeral is neither a retreat to (imaginary) bliss nor a disintegration into despair. Instead the strange weight of death settles over the church like a veil, all tears and concealment threaded with dignity and relief. A veil is not nothing. It also isn’t everything.

Can the Church herself die, and can we then mourn her? I wonder and tremble at the possibility, and sometimes think of Holy Week as a funeral. A death not unlike that nun’s: a prayer-cry surrender in the sundering dark. Christ’s dark.

There is a way in which the Church cannot die. Her life is the Spirit’s, who knows no death. But this says nothing of her members, who can whither cut from the vine. This says nothing of the way the Church lives her eternal life. In Hans Urs von Balthasar’s Heart of the World, Christ says to the Church,

The source of your life, O Church, is both a demand and a promise. … Bind yourself to me so irrevocably that I will be able to descend to hell with you; and then I will bind you to myself so irrevocably that, with me, you will be able to ascend to very heaven. … I will spare you no extremity – not the heights and not the depths – for I wish to have no secret from you. Where I am, there you too are to be (198-99).

So it is that the Church lives the whole reality of the cross, both the mournful death and the unveiling of new life. There is a way that she dies and rises in Christ, but also in her members. Even to become a member is to die: in baptism, the old Adam passes away and the New rises. Once a priest said to me, “Your baptism is still trying to kill you. Working to make the old Adam in you die.” Baptism is God’s permanent touch, even to the soul that dies a spiritual death.

Which is, again, so very strange. That a sacramental character can remain even in one who succumbs to total despair. But no darkness isn’t Christ’s.

And I wonder if Christ – or how Christ – is present when I watch the structures of the Church die. I mean when parishes close, when communities fade, when sheep leave the fold. Or as I watch the Brothers at Saint Mary’s slowly die. Should I remain at the college, I will eventually watch them all die. There are so few already, and though I try to leave the end to God, I do see one in sight.

Who will teach me how to mourn this? Who will bear the veil with me? To be Catholicism in all the dignity of her mysterious vanishing in the tide. Something does die as the Brothers do, and I know this too is Christ’s. I just don’t know quite how, or how to bear its weight. I know that every death is a sign of the resurrection, but this is one I have learned no songs for. I never even knew them in their prime. Weirdly, I mourn the death of that too. For me and for them. I’d have liked to know it.

I am not worried about the fate of the Church. This isn’t a comment on the fate of Catholicism at the college, though of course that will irrevocably change (and has). I am wondering how to live in the midst of a death that is too much for me to understand. I want to be able to talk about it, to mourn. To cry and to hope. I am so tired of the rush to fix or to fight.

I think this too of my own losses and my own sin – and these are not the same. Who will teach me to mourn them?

As deep calls to deep, and the saints look on from behind their veils.