In honor of Thank A Teacher Day: the following is a slightly edited version of a post I wrote for Catonsville Patch over a year ago. You can read the original version here.

The lilting, closing notes to Brahms’ Waltz in A Flat Major still rang in the air. (We had an actual pianist playing an actual grand piano in the studio when I took ballet.) We would have just completed our rond de jambe exercises at the bar, and we would be waiting. Silence. We’d stand like statues in our closing pose, hands down delicately, elbows gently bent, feet in fifth position, head tilted just so.

A few of the braver and more impatient 10-year-olds among us would break the pose slightly to check on his reaction. One of them would giggle a little, nervously, and then we all knew what we’d see when we turned to look at him.

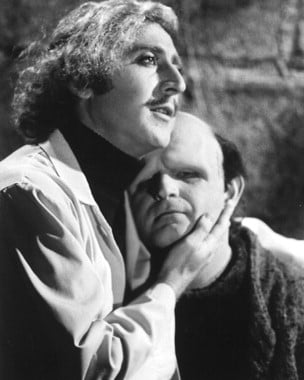

Mr. Andros, sitting on a stool in the front of the room, beefy legs crossed at the knee. One large arm flung around resting on the barre behind him. The other large arm in the other direction, bent at the elbow and also leaning on the barre. The bridge of his nose resting between thumb and forefinger, pinky in the air. Eyes closed, but eyebrows raised.

And then we would hear it – the voice that was a cross between Squidward from Spongebob and Bert from Sesame Street.

“Laaaaaaay-deeeeeeeeez…………………. If you can’t count to four, I suggest you take upknit-ting.”

(No one bothered to point out to him that you also need to count to four when you knit. You didn’t quibble with Mr. Andros.)

Gray-ish beard and moustache, black unitard, white socks, white ballet shoes, and a little sheer scarf tied around his neck if he was feeling dressy, age placed by me at anywhere between 40 and 90 years old, Mr. Andros was my favorite ballet teacher. Ever. In fact, my parents and I did as much as we could to make sure he was my ONLY ballet teacher, though over 8 years of classes at the New York School of Ballet, that was tough to accomplish.

We were young, but we all took dancing pretty seriously. This was not a ballet school for sissies. He, in turn, was demanding, but mindful of our youth. His exasperation wrapped up in mock agony did absolutely nothing to hide how much he adored these groups of hopeful little girls.

He would ball up his hand into a fist and walk around us asking, “How would yyyyyeeeeewwwwwww like to be the first ballerina on the moon?” We’d giggle, but try harder.

He would explain how a grand jete is done, and demonstrate the leap for us. Then he’d roll his eyes and say, “Of course when I do it, it looks like the Hindenburg flying through the air…” We had no idea what the Hindenburg was, but we’d try to do it better than he did.

He sat down with parents of this pre-teen girl, and spoke the words I knew he would, when they asked if I had any sort of shot in hell of being a professional ballerina. I cannot begin to explain how badly I wanted with all my being for the answer to be yes. Deep down, though, I knew I didn’t, and I think my parents did, too.

I wasn’t in the room, but I imagine it was the utmost gentle kindness he told them I would never be a prima ballerina. While I was really good at duplicating moves demonstrated by him, I lacked strength, flexibility and the grace required. I just didn’t have it.

Cordelia had it. Cordelia was the same age as I was, but destined to be a ballet dancer. Cordelia likely emerged effortlessly from the womb with her entire body in the perfect fifth position. I’m sure as soon as her nose and mouth were suctioned out, she began pirouetting all over the delivery room. She was proportioned perfectly for a life of dance, the flawless combination of delicate yet strong and flexible. She was allowed to do our class in pointe shoes, while the rest of us were still years away from going on pointe. She was that good.

Yet, on one Parents’ Day (we didn’t have recitals – we had a couple of days a year when parents could come watch the class in session) I’ll never forget the time we all did a combination in the center of the room. When it was over, Mr. Andros was in his pose, sprawled all over the barre in exasperation, eyes closed. Then he said something like, “Would the Lirtzman sisters (Rachel and me) please come to the front of the class?” We did, and in front of all the parents and the rest of the class, he cued the pianist and had us perform the combination.

When we finished, he said, “Thank you. That is how it’s supposed to be done.”

Most teachers help you succeed. The rare ones help you fail. Mr. Andros helped me see my limitations while making sure my self-worth and dignity remained intact. I could let go of a dream without feeling like a failure. Lesson learned.

(Epilogue: Years later, my parents ran into Mr. Andros on the Upper West Side. They were happy to see each other, but my parents told us he didn’t look at all well. As I began to write this, I assumed he died many years ago. I Googled him this afternoon for the hell of it, and was surprised to learn he only passed away in 2009, and had left a lot of writing behind. I am so sorry I didn’t try to get back in touch with him to let him know how much he meant to me and my family, as it would have been so easy given the advent of the internet.

I’m happy, though, that he lived such a long life, and that he was kind enough to leave behind writings about it. I never knew until this afternoon that he studied with George Balanchine and also taught the likes of Cynthia Gregory, Veronica Lake and JoAnn Woodward. I learned that and when Mr. Andros was in the army, he was assigned to the Special Service Division of General Douglas MacArthur’s Headquarters Company and that his older brother, Plato Andros, played for the St. Louis Cardinals. It’s a pleasure to get to know him better, even if it is posthumously. R.I.P., Mr. Andros.)