The recent attacks in Paris and Beirut are horrible and shocking. There is no excuse for such indiscriminate violence.

But these events, like every previous horror of human violence, had causes. And if we want to prevent future horrors, if we want to do more than scream with pain and rage, we must understand those causes, and take care that our responses to horrors are not part of a causal chain that leads to the next horror.

What motivates the footsoldiers of DAESH (a.k.a. “ISIS”)? One DAESH fighter taken prisoner in the Kirkuk Kurdish autonomous region in Iraq, was interviewed by researchers for conflict resolution consortium Artis Research:

He knows there is an American in the room, and can perhaps guess, from his demeanor and his questions, that this American is ex-military, and directs his “question,” in the form of an enraged statement, straight at him. “The Americans came,” he said. “They took away Saddam, but they also took away our security. I didn’t like Saddam, we were starving then, but at least we didn’t have war. When you came here, the civil war started.”

These remarks were directed to General Doug Stone, who said the prisoner had “exactly the same profile as 80 percent of the prisoners [during Stone’s deployment in Iraq]…and his number-one complaint about the security and against all American forces was the exact same complaint from every single detainee.”[Wilson]

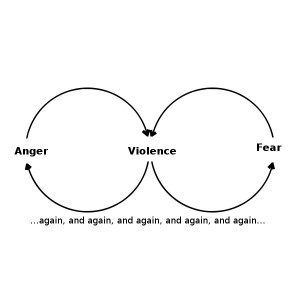

People take up arms for DAESH in part as an angry and counter-productive response to the invasion of Iraq and the ruination of the social order there. The U.S. invaded Iraq as angry and counter-productive response to 9/11. The 9/11 attacks were an angry and counter-productive response to American intervention in the Middle East since the First Gulf War. The First Gulf War was a fearful and counter-productive American and European reaction to geopolitical shifts that threatened their access to oil.

Those geopolitical shifts were largely a fearful response to the end of the Iran-Iraq war. The Iran-Iraq War was to a significant degree a fearful response to the Iranian Revolution in 1979. The Iranian Revolution was a reaction to the rule of the U.S.-supported Shah, going back to the CIA-backed coup that put him into power. The coup orchestrated by the American CIA — and the UK’s SIS — was an angry and fearful response to that nation’s democratically elected Prime Minister’s move to manage Iraq’s oil resources on behalf of the Iranian people. And so on, and so on.

This is of course a great simplification of history but I think the point holds: trace back any act of violence to the roots and you’re likely to find fear and anger. Anger at past acts of perceived violent injustice, and fear of future violence or of poverty and deprivation.

The anger may or may not be justified. The fear may or may not be rational. But it matters little to those slaughtered and maimed or to their families and friends, and so the survivors become angry and fearful and lash out, and the vicious cycle comes around again. And again. And again.

I sure as hell don’t have an answer. Times like this it feels pointless to suggest that, hey, maybe we could find ways to live together that started with some inner peace leading to a little more sharing and caring and a little less killing and stealing.

I just have the same sick feeling I had after 9/11: if we act from anger and a desire for revenge, we will be trying to put out a fire with gasoline. That’s what we did in 2001, and I fear we’re just loading up more gasoline now.

As a Discordian, there is a story I think of at times like this.

It’s about Joshua Norton, the mad wise man who in San Francisco in 1859 declared himself Emperor of the United States. Emperor Norton disbanded Congress (a move that seems wiser with every passing year) and sidestepped the banks by issuing his own currency. His antics were generally regarded with amused tolerance by citizens of San Francisco.

Except for one night when things got very serious. At that time there was a lot of anti-Chinese racism — a fearful reaction to Chinese immigration. Violence was not uncommon.

As told by Kerry Thornley in his introduction to the Fifth Edition of the Principia Discordia:

One night a gang of vigilantes gathered for a pogrom against San Francisco’s Chinatown. All that stood in their way was the solitary figure of Norton. A sane man would not have been there in the first place. A rational man would have tried to reason with them. A moralist would have scolded them. A man as daft as Norton usually seemed would have loudly ordered them to cease and desist in the name of His Royal Imperial authority. All such tacks would probably have been futile, and Norton resorted to none of them.

He simply bowed His head in silent prayer.

The vigilantes dispersed.

Discordians believe everybody should live like Norton.[Thornley, xv]

And if it seems ridiculous to cite the scriptures of Discordianism, a religion often classified as a parody, at a time like this…well, look at what the “serious” religions are doing to the world. I’ll be over with the Emperor.

References

Thornley, Kerry. Introduction. Principia Discordia. By Malaclypse the Younger. Lilburn, Georgia: IllumiNet Press, 1991. i-xxxiv. http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~tilt/principia/intro5.html

Wilson, Lydia. “What I Discovered From Interviewing Imprisoned ISIS Fighters”. The Nation 21 Oct 2015. http://www.thenation.com/article/what-i-discovered-from-interviewing-isis-prisoners/.