I’ve been working for a while to build a positive spiritual vision of masculinity. Indeed, here at TZP we’ve just completed the first half of a series about archetypes of mature, sacred masculinity.

And in one of my other hats, as a martial arts teacher, I’ve taught self-defense to both women and to men. I’ve spent more than a few hours poring over FBI statistics on violent crime, reading criminology papers, talking to survivors of attacks (both men and women) about their experiences, trying to get an idea of the actual shape of the perpetration of violence.

So I’m disappointed at the virality of the “men vs. bears” memeplex (i.e., the internet meme and the discussion around it), which suggests that it’s good and sensible for a woman to have a greater fear of encountering a strange man while hiking in the woods than of encountering a bear, that we ought to think of men as more threatening than wild animals, and that it’s the responsibility of men to “do better” to address that fear.

It’s my hope that by taking some time here to deconstruct this ill-informed and badly reasoned memeplex, we can make space for more productive discussion towards a positive vision of manhood and a safer society.

There are several reasons that the discussion here is are problematic. In this memeplex we can find misandry, a romantic misview of nature, a base rate fallacy, myths about violent crime and about the gender distribution of power, and a disregard of positive helping behavior by men. So there’s a lot to unpack.

Misandry

To quickly and vividly illustrate the problem: if we asked racists if they’d rather encounter a bear or a black person in the woods, their answers would say more about racists than about the threats either meeting poses.

Indeed, when a white woman encountered a black male stranger in the woods in Central Park in 2020 and called the police after he made an ambiguous but intimidating statement that made her afraid, the incident became a cause célèbre among progressives. Many of the same people now participating in this memeplex were horrified that this woman jumped to conclusions about the danger the man posed.

No one suggested that it was up to black men to address this woman’s fear, or to “hold each other accountable”. Instead the woman was publicly shamed and “canceled”, became an exemplar of the “Karen” meme, and lost her job. (For clarity, I think she over-reacted to the situation, but that the public response to that was also an overreaction. She had the bad fortune to do a somewhat dumb thing on the same day a black man was egregiously murdered on video by police, and American society sort of broke.)

But the reasoning is the same if we take the “black” out of that question and address just the “man” part.

Just as the idea that black men should be treated as predators until proven otherwise is a form of bigotry called “racism”, the idea that all men should be treated as predators — or are somehow responsible for the actions of the fraction of men who are — is also bigotry. The word for such sex-based bigotry against men is “misandry.”

The Central Park birdwatcher incident shows that spreading unfounded fears about men can cause harm: activating the police without good cause is a dangerous act that can lead to false arrest or physical violence.

And even though the people in power in our society are disproportionately men, such anti-man bigotry does matter. We’ll come back to that point.

Note that these facts are independent of the experience of the person making a bigoted statement. “I’d feel safer meeting a bear in the woods than a black stranger” is a racist statement, whether the person saying it has experienced trauma at the hands of black person or not; we demand that they reason past their personal experience. Just so, “I’d feel safer meeting a bear in the woods than a man who was a stranger” is a sexist statement, whether the utterer has experienced trauma at the hands of a man or not.

So this is not about denying that people have been victimized or traumatized! It is about not allowing those experiences to develop into bigotry and prejudice, about seeing abusers as individuals rather then as reasons for identarian bias.

And let’s be clear that this does not mean that we should not take reasonable precautions when dealing with other human beings. We absolutely should, and we should urge others to do so! But we can do that in a manner that is not rooted in prejudice.

And we should take such precautions when dealing with wild animals too, something omitted from much of the current discussion.

A Romantic Misview Of Nature And A Base Rate Fallacy

I am Pagan, which means that I find a fundamental worth in Nature. I think that it should be preserved and protected and appreciated, and that we should generally live in alignment with it rather than trying to conquer it.

But while Nature is beautiful, it is also terrible. It can kill you quite dead in a number of ways, from disease to starvation to poisoning to being killed by a wild animal.

I’m not on the side of Hobbes’s contention that life in a natural state is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”. But romanticization is problematic. Some of the discussion here has veered in that direction, with people posting cartoons or cute photos meant to invoke a certain notion of bears.

Indeed our whole cultural notion of bears in specific has been shaped by the “teddy bear” and by circus performing bears. Bears are cute, bears are friendly, dancing bears are a subculture icon.

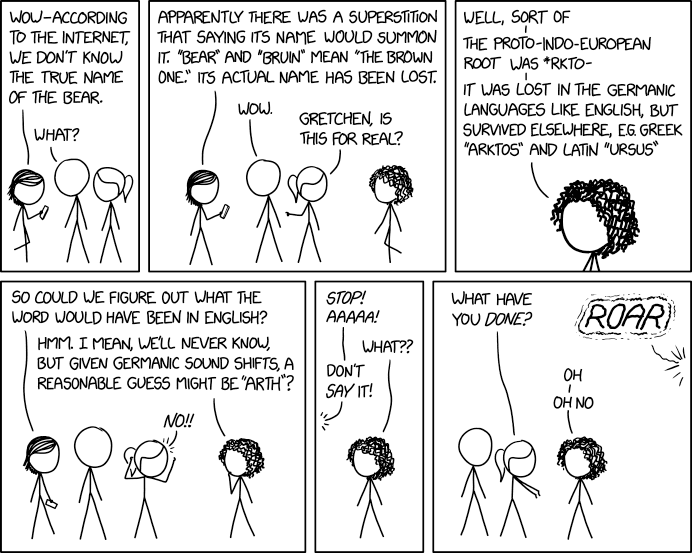

It’s seriously distorted from the views of our ancestors who shared a more wild world with them, formed religious cults in awe around them, and were so intimidated that they wouldn’t even speak of the animal directly — in Germanic (including English) and Slavic languages, the common word for “bear” is a rooted in a circumlocution for “the brown one” or “the honey-eater”.

To put it in the argot of the times, perhaps we might say that those taking a cartoonish view of the bear, rather than seeing the terrifying Big Fellow Whose Name We Do Not Speak, are taking a “settler colonialist” view of the forest.

In any event, it’s true that bear attacks on human are rare, and so in that sense a bear attack is less of a threat to us than an attack by another human being. But close encounters between bears and unarmed humans (i.e., discounting bear hunters) are rare, while close encounters between humans are commonplace.

Comparing the number of human-on-human attacks with the number of bear-on-human attacks is a serious base rate fallacy. Let’s illustrate that with some arbitrary numbers — i.e., these are made-up numbers, meant to be reasonable enough to show the factors at work, but not to be accurate.

Let’s say that 5% of men are “dangerous” to some arbitrary degree. And let’s say that twice the proportion, 10%, of bears are “dangerous” to humans to that same degree.

But in your life, you will encounter thousands of men. If you closely encounter 2,000 men in your life, you will encounter 10 dangerous men.

In comparison, your likely number of close encounters with bears is less than one. Let’s say that 1 in 100 people will closely encounter a bear in their lives — not just see one in a zoo, or digging in the trash cans down the street, but as up close and personal as those “close encounters” with men.

Then 1 in 1000 people will encounter a dangerous bear. The average number of dangerous bears encountered, given our assumptions, is 0.001. One one-thousandth of a bear. Four orders of magnitude less than the 10 dangerous men you’ll encounter — even though we’ve assumed that bears are twice as dangerous as humans.

The reason you are so unlikely to have a close encounter with a dangerous bear is not because all bears are cuddly soft dancing friends, but because you are unlikely to have any close encounters with bears. The reason you’ll encounter several dangerous men in your life is not because a high proportion of men are dangerous, it’s because you will encounter a lot of men.

Again, these numbers are not meant to be pin-point accurate. Maybe you’ll meet 20 dangerous men on average. Maybe the correct rate of people having encounters with dangerous bears is one in ten thousand rather than one in a thousand. But this example illustrates the factors involved.

So don’t let a base rate fallacy, or romanticization of Nature, fool you into thinking that close encounters with wild animals pose no danger. A lot of people are projecting fantasies onto the natural world.

The Myth Of The Stranger In The Bushes

Another matter of bad statistics here comes from how the meme represents the danger posed by strange men.

According to the FBI’s Expanded Homicide Crime statistics for 2022, in that year’s homicides where the offender’s sex was known, there were 15,094 murders committed by men and 2,107 by women.

About seven times more men as murderers than women (assuming the same rate of killings per murderer) — a very strong difference, but not an absence of female offenders. That’s mostly in line with what people expect, though many expect the difference to be even stronger than it is.

But many people are surprised to learn the other side of the question. There were 14,993 male victims and 4,118 female victims. Men are three and a half more times likely to be murdered than women are.

So just by those raw numbers, if a woman should be scared of meeting a strange man in the woods, a man should be absolutely terrified.

There are a lot of additional complexities about who commits and who is victimized by homicide, but these numbers should point up that the issue is not men versus women. It’s the majority of men and women against the small percentage of predators in our midst — who are disproportionately, but not exclusively, men.

Beyond that, the meme deals with the danger posed by a stranger. But only 12% of murders of women (based on 2021 data) are committed by a stranger. (21% of male murder victims are killed by strangers.)

Of course murder is not the only way a person can be attacked. Our data about criminal victimization is clearest for homicide — a dead body is almost always reported to the police, while other crimes are made murky by reporting rates and questions of definition, and by failing to include cases that happen in prisons or in the military. Rape statistics are especially prone to these problems.

But one thing we do know about rape is that most rapes are not perpetrated by the stereotypical stranger waiting in the bushes for a victim. Like homicides, in most cases the attacker is someone the victim knows.

A stranger passed while hiking in the woods is not the person a woman (or a man) needs to be most wary of. We’re most likely to be harmed by people we know.

In part this is because predators camouflage themselves well, hiding among us to get closer to their victims. Human predators don’t find their prey out in the woods, they find them in society. The rapes (allegedly) perpetrated by Bill Cosby are an excellent and horrifying example of how predators actually work.

And partly the reason we’re more likely to be harmed by someone we know is that it usually takes some interaction with a person prone to violence to set them off. A stranger doesn’t have the motive to do us harm that an abusive spouse, or a co-worker we argue with, or someone we’ve met who becomes a stalker, does.

By promoting the “stranger danger” myth, and failing to put the context of violence against women in a context that includes violence against men, the memeplex does real harm to our ability to understand violent crime.

Men Help

There are many things that can go wrong while hiking in the woods. In a world of cellphones and search-and-rescue teams with advanced technology, where most people’s idea of “the woods” is a local park, it can be easy to forget the dangers posed by the deep forest.

But as we’ve already discussed, Nature is both beautiful and terrible and can kill you quite dead. Imagine that while you’re out hiking in the deep forest, out of cell phone coverage (yes, such places exist!), Nature takes a swipe at you, and you fall and break your ankle.

Who would you rather see next: a bear, or a male stranger? Who is more likely to help you?

The voice of fear would have you imagine that such a stranger would be a predator who would take advantage of the situation, rather than someone willing to help. But men are as likely as women overall to engage in helping behaviors, and more likely to do so when physical strength is called for — in keeping with gender roles of chivalry and heroism.

Do an internet search on news stories for “man helps stranger”, and consider whether a typical man is more like the ones in those stories or more like a serial killer you should be afraid of.

Now let’s be clear: when you meet a random stranger, you don’t know if they are a trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean, and reverent Boy Scout, or a sneaky, underhanded, lying, and exploitative abuser. Just as if you see a bear in the woods you don’t know if it’s a rabid or not. So you take reasonable precautions, in either case.

But if you presume that men you don’t know are abusers, you will create conditions that make it impossible for men you don’t know to help you when you need it. By promoting the idea that men should be presumed dangerous, the memeplex does real harm to our ability to engage in mutual support.

The Myth of Social Accountability

One odd claim that has come up in discussions around this memeplex is that while only a small percentage of men are actively bad, the rest of us fail to hold that small group “accountable”, and so bear some blame for their actions.

One commenter compared it to the situation with police: if 10% of officers are bad cops, but the other 90% fail to hold them accountable, then all cops are bad – one rotten apple spoils the whole bunch.

We can see the flaw in that logic by applying it to a different case. By this argument, if 10% of women are “mean girls” who engage in indirect aggression, but the other 90% fail to hold them accountable for that aggression, then all women are at fault and need to “do better”.

But we immediately see the flaws here. Unlike being a cop, being a woman is not a matter of choice, and so a woman cannot be held responsible for the behavior of other members of the group. Police abuse generally takes place in the presence of other police who know the abuser, while indirect aggression by a woman might not be obvious to her friends. And while there are legal structures to bring a police officer before an authority to give an account of their actions and face consequences, there is no way for women to hold each other “accountable” in a meaningful way here — the most a woman could do is stop being friends with the “mean girl”.

And the same is true for men dealing with abusers among us.

I know entirely too many women who have been abused by partners or boyfriends. But not once have I ever heard a man say “I think I’m going to go home and abuse my partner, what do you think about that?”, giving me the opportunity to speak up. And the sort of man who’s going to abuse others does not give a flying fig if I did speak up — he’s likely to be a bully and abuser towards other men as well as women.

(On an handful of occasions I’ve seen men be aggressive towards women — or towards other men — and I have stepped in. That’s an example of how men help, even at risk to their own safety. But that was a matter of preventing specific acts, not of “accountability”. And two or three occasions for action over decades is not a handle for social change.)

This one is personal for me, because my own younger brother was an abuser. He was an alcoholic who hid his alcoholism from our parents and me for decades; when it came out, a former girlfriend of his confided in me how he had been abusive when he drank. To top it off, in his last few years he also stole money from our mother.

There was no opportunity to “hold him accountable” for this. The only thing that I could do was cut him out of my life when I found out about his abuse, years after the fact. But that didn’t undo the harm, didn’t motivate him to reform his ways, didn’t result in any accountability. It just meant that he died estranged when cheap rum finally rotted his circulatory system.

My father, my mother, and I all did our best to try to guide my brother when he was growing up, and to encourage him to reform when we saw unhealthy behavior. (Though how unhealthy, we had no idea at the time.) But if there was nothing his own flesh and blood could do, how can other men in general be demanded to be accountable for his behavior?

Instead of believing in a fantasy of men holding each other accountable through some informal social means, we all — men and women — have to work together to build a criminal justice and mental health system that deals with predators and abusers, and work on ways to educate and nurture young people to reduce the risk that they grow up that way.

Men And Power

Blaming all men for the actions of the fraction of men who are predators is intellectually and morally wrong. It is literally prejudice, no different in nature than blaming all Muslims for the actions of Islamist terrorists, or all black men for the crimes of O.J. Simpson or Bill Cosby.

So why does it feel different to many people who think of themselves as “progressive”?

It feels different because some people have fallen into the thought-trap of identarianism. Some people look at the world, see that the people in power have historically been disproportionately men (white and Christian men, in the Western world), link the identity of “man” with the property “powerful”, and conclude that for a more just world, we must take power away from men by any means we can.

But “people in power tend to be X” does not mean “people who are X tend to be in power”.

That’s important so let me repeat it: “people in power tend to have characteristic X” does not imply “people who have characteristic X tend to be in power”.

In our society men are also more likely to be found at the bottom of the power hierarchy: in prison, in jobs with high risk of death, as cannon fodder in the latest war ginned up by the men at the top. We’re more likely to end up as high school dropouts — or, as we discussed above, as murder victims — than women are.

Billionaires are more likely to be men than to be women — but homeless people are also more likely to be men than to be women.

The precise nature and reasons for the distribution of power is the sort of complex topic that requires thick academic tomes, not an essay about an internet memeplex, to properly investigate. What’s important for our purpose is the much simpler point that we cannot take the premise “this person is a man”, and from it and it alone arrive at the conclusion “this person has power”.

So prejudice against men is not a valid way of “getting back” at the powerful.

Fear of Maleness Is The Root Of Trans Exclusion

One more point illustrates how the fear of men being sold in this memeplex is not socially progressive.

The author J.K. Rowling is widely known as an advocate for the exclusion of transgender women from traditional women’s spaces. She writes,

I am strongly against women’s and girls’ rights and protections being dismantled to accommodate trans-identified men, for the very simple reason that no study has ever demonstrated that trans-identified men don’t have exactly the same pattern of criminality as other men…

Rowling’s skepticism about inclusion is rooted in fear of a “pattern of criminality” among males. It’s ironic that many of the people participating in this memeplex have been critical of Rowling, yet are spreading an identical belief that males have an inherent “pattern” of violence and crime.

(To clarify my own stance here, I think that we can find policies where a trans woman can use a women’s bathroom without being harassed, without also saying that convicted male sex offender should be able, with no other criteria, to identify as a woman and serve their sentence in a women’s prison. This is not prejudice, not rooted in any general belief about men or maleness. It’s judging people like David Thompson/Karen White specifically on their own dangerous and harmful actions.)

Conclusion

On the community level we all need to work together to identify and stop predators in our midst. We need criminal justice and mental health policies that constructively deal with such people (men and women, though disproportionately men) with a goal of rehabilitation, and social welfare policies that make it possible for people to leave abusive relationships.

And we all should work to raise boys and young men (and girls and young women, though it’s statistically less of a concern) in a way that keeps them off the path of becoming predators.

But don’t be afraid of men or maleness. We need a positive spiritual vision of masculinity in order to guide boys through the transition to healthy manhood. A social milieu that fears men, sees us as likely demons who need taming, doesn’t help us raise boys to be good men, it hinders us.

Be a little noisy when you’re walking in country where the Big Fellow lives to let him know you’re coming, so you can avoid close encounters.

Don’t be identarian. Don’t promote prejudice. Work against sexism and racism in bigotry in all their forms.

Be reasonably wary, of people and animals. Naivety only serves predators. But also be reasonably kind and helpful, to both strangers (in the woods and elsewhere) and to people you already know.