I. An except from a debate between an idealist and a materialist:

Materialist: …And so, my friend, if we are not to be stuck in a dead end of some sort of non-falsifiable solipsism, if we accept the axiom that some sort of external world more or less matching our perceptions exists, if we make the unprovable but very useful assumption that I’m not a butterfly dreaming I’m a man, then according to the best evidence we have about that external world, ideas correlate with things that happen in brains, yes? The mental supervenes on the neurological. Yes, we’re still figuring out exactly how, but we know that we can cause mental events (or, to be more precise, the reporting of mental events) by stimulating the brain, and we can observe how brain activity correlates with mental events (or the reporting thereof).

Idealist: Well…

Materialist: And brains are biology! They are living tissue, which can be studied by the methods of anatomy and physiology, of the various disciplines of biology. And biology, in the end, supervenes on chemistry. Not that we understand all the details, but the idea of some élan vital can surely no longer be taken seriously. Biological phenomenon are the very complex interactions of proteins, nucleic acids, fats, various ions in solution, carbohydrates, and the like. Right?

Idealist: Okay, I’ll give you that one. In order to affect the physical bodies of living organisms an élan vital would have to be a form of physical energy anyway, so it’s really no points against my side.

Materialist: And chemistry is just applied physics — again, not to say that we understand it all or ever will, but we can assert confidently that all chemical phenomena have a basis in atomic physics. And the phenomena of atomic physics have basis in particle physics. All of the “ideas” that you say are the ultimate constituents of reality are nothing more than the very complex interactions of the particles and fields of the Standard Model of physics! And that model is well backed up by empirical data.

Idealist: Well, maybe that’s true from a certain point of view. But what did you just say these particles and fields are part of?

Materialist: The Standard Model. Our best understanding of fundamental physics. Yes, there are still gaps, but we’ve got a pretty solid outline.

Idealist: Oh, that’s fine, since our data is always finite I’ll allow your side some gaps. It’s that “model” part that’s interesting.

Materialist: How do you mean?

Idealist: Let’s start with this question: can you point at one of these “particles”? Directly, I mean, not as a track in a particle detector? Can you perceive one of them as part of your direct experience?

Materialist: Well, no, but…

Idealist: So as much as you talk about empiricism, these particles are not part of your empirical experience? There is a good deal of theorizing that connects your sensory perceptions with this supposed evidence?

Materialist: Yes, but am I supposed to ignore the reports of others? And the information we can gain from inductive and deductive reasoning?

Idealist: No, but it’s worth noting. Let me come back to that in a minute. Now, it’s the Standard Model that links that perceivable track in the detector with the positron or muon or alpha particle, right? That is, among various models, the Standard Model gives us the best available explanation of the size and shape and position and whatever of that track?

Materialist: True enough.

Idealist: And what is a model? In this scientific sense, I mean, obviously we’re not talking about model trains.

Materialist: Well, the Standard Model is a mathematical model. It’s a way of describing a system using mathematics.

Idealist: Of describing a system? To other physicists?

Materialist: Sure.

Idealist: So this standard model is a way for physicists to talk to other physicists, using a common language — mathematics. Right?

Materialist: Yeah, that’s a fair way to put it.

Idealist: And language, you must surely admit, is a sociological phenomenon.

Materialist: I don’t quite follow you.

Idealist: Language is not a given. And one person can’t invent it, right? If you dropped a newborn baby on a desert island along with a machine that saw to all of its physical needs but never spoke, that baby would not grow up to speak any language. Language is learned, on an individual level, and develops, over a long period of time, on a societal level. You can’t have a language without having some sort of society.

Materialist: Okay.

Idealist: So anything we can use language to talk about or write about, any linguistic phenomenon, is a social phenomenon.

Materialist: Well…

Idealist: And, to get back to an earlier point, inductive and deductive reasoning are also social phenomena.

Materialist: What?

Idealist: Were you born with the ability to perform inductive and deductive reasoning? That baby on a desert island wouldn’t be able to reason, right?

Materialist: I suppose not.

Idealist: So the making of mathematical models, and logical reasoning, are social phenomena. And the agreement that the Standard Model is the best model, that process of peer review and scientific consensus, is a social phenomena. And social phenomena are nothing but psychological phenomena acting en masse. You don’t have human societies without having individual thinking humans — in other words, humans with ideas! The “Standard Model particles” that you say are the ultimate constituents of reality, as well as the patterns of reasoning that you say lead to it, are nothing more than ideas!

Materialist: Well, maybe that’s true from a certain point of view. But where are these ideas?

Idealist: Hmm?

Materialist: Can you point at an idea? Can you observe an idea? Outside of your own subjective experience, I mean.

Idealist: Of course not. But…

Materialist: And if you’re only going to allow your own subjective experience, you can’t rule out being a brain in a vat, or Chuang Tzu’s butterfly dreaming he’s a man. But those sort of ideas are inherently non-falsifiable. There’s maybe a certain aesthetic pleasure in considering them, but if we want arrive at useful conclusions about the nature of the world, “Maybe we all live in the Matrix!” or “Maybe I’m the only real person and I’ve been living my life in some sort of massively multiplayer online role-playing game!” is a dead end.

Idealist: Sure.

(As the musicians say, Da Capo — back to the start.)

II. Circles Big and Small

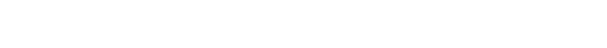

When we say something is a circular argument, we usually mean that it assumes its conclusions and chases its own tail so tightly that nothing can be inferred from it. For example: the Bible is literally and completely true; we know this because it’s the Word Of God; we know this because the Bible tells us that it is the Word of God; and we know we can rely on the Bible’s statement that it is the divine word because the Bible is literally and completely and true.

I don’t mean to imply that all Christians believe this, by the way — I was raised Catholic and we were never taught Biblical literalsm. (Heck, it was a Catholic astronomer who proposed the “Big Bang” theory.) But this sort of belief in the literal infallibility of some scripture or another is a distressingly common argument.

Now this Biblical argument makes a small circle, one that encompasses nothing but the Bible and that part of the mythology of Christianity that it contains. Can we derive any propositions about biology from it? No. Anything about sociology, linguistics, physics? No. It does not give us any data that we can compare with our experience.

On the other hand — and here I freely admit that I am stepping out into thin air with no support, and may even be leaving philosophy being and falling into poetry — what if we could make a circular argument large enough to encompass our entire experience of the world?

Reductionism is an ancient idea, dating back at least to the ancient Greek philosophers who proposed that everything is made of atoms. (Their idea of atoms was rather different than our modern physical/chemical one — an “a-tom” is something that cannot (a-) be cut or divided (-tom), so the quarks and leptons and gauge particles of modern physics are closer to being “atomic” in the original sense than is an atom of hydrogen or uranium.) In this atomic view there is one level of absolute and true reality, and everything else is a mere epiphenomenon, a handy way of talking about a bunch of atomic interactions at once.

This idea was one of many for those old Greeks, but it really took hold during the Enlightenment up until to the early 20th century and worked quite well. We were able to use this strategy to make predictions about the observed world, and use that predictive knowledge to manipulate the physical world to give us the steam engine, electric power, antibiotics, space probes, and the like. As Uncle Walt put it, “Hurrah for positive science! Long live exact demonstration!”

But then we started to bump up against some fundamental questions about physics and the nature of observation.

Now I want to be clear that I’m not invoking any quantum woo or “consciousness causes collapse” hand-waving. But as we got to looking at smaller and smaller phenomena, we could no longer gloss over the fact that the way we receive and process information about those particles interacting “out there” was via a chain of the same sort of interactions as the one we were looking at.

In other words, when my high school physics teacher demonstrated the conservation of energy with a bowling ball pendulum swinging at my head (true story, we were inspired by a scene in Carl Sagan’s novel Contact), the way in which we observed that was via photons interacting with the ball and with my head and with the eyes of the class, a phenomenon on a scale so much finer than the swinging weight that it was lost in the noise and could be ignored for all practical purposes. But when we set out to observe the decay of a muon in a particle accelerator, our observation relies on phenomena of the same order as that which we are setting out to observe.

And so we run into fundamental questions of epistemology. What does it mean to observe something? What right do we have to make statements about things we observed in the past but are not observing now, or about things that common sense or physical theory say should be the case but we haven’t observed directly? It turns out that the intuitions about these matters with which natural selection programmed the brains of our distant primate ancestors, the intuitions that kept them from getting eaten and allowed them to survive long enough to breed and thus become ancestors, aren’t necessarily of great use when doing particle physics. (Or cosmology, as Einstein showed us.)

So physics starts to shade off into philosophy, into the realm of ideas.

But over the past century or so, we’ve also come to have some meager understanding of the workings of the brain, of the palace of ideas.

We can trace idealism also back to those old Greeks, to silly old Plato and his buddies who would be shocked at what we’ve figured out about the brain.

Much, indeed most, is still hidden and obscure, but we have some ideas about the electrochemical operation of axons and synapses. We’ve reached inside the skull and tickled parts of the brain and had it report of the experiences thereby produced. It’s clear that mental events supervene on physical phenomenon of the brain.

The physicalist has had to come to some accommodation with the world of ideas — while at the same time the idealist has had to make some peace with the fact that the mental supervenes on the physical.

Students of the history of philosophy — of “philosophology”, to use Robert Pirsig’s word — may object that in my fictitious dialog above I’ve bent both materialism and idealism. And perhaps I have; one must bend determinedly parallel lines of inquiry in order to make them meet. (At least, if one accepts the axioms of Euclid.) But if we do bend them — and I think they are ductile enough to take it — we arrive at a remarkable sort of circular argument. Unlike the Biblical argument mentioned about, or similar circles of small circumference, this circular argument is large enough to encompass the entirety of human experience.

But the idea of two opposite but complementary principles, each dependent on the other and together encompassing the whole of reality, is not a new one. It’s another example of the principles the ancient Taoists called yin and yang: opposing, mutually interdependent, supporting each other, transforming into each other at the extremes, and infinitely divisible.

If we take these two ancient streams of thought, idealism and physicalist reductionism, ideas that go back to the Greeks and the roots of Western culture; and put them into a framework of yin and yang from the roots of Eastern culture…maybe we can find an idea big enough to encompass the universe.

You can keep up with “The Zen Pagan” by subscribing via RSS or e-mail.

Have I mentioned my book lately? Why Buddha Touched the Earth makes a great Yule gift for the Zen Pagan on your list.

If you do Facebook, you might choose to join a group on “Zen Paganism” I’ve set up there. And don’t forget to “like” Patheos Pagan and/or The Zen Pagan over there, too.