These are the notes for the talk “Why The Moment Calls For Magic” that I gave at Starwood 2019, discussing Daniel Lawrence O’Keefe’s ideas about magic from his book Stolen Lightning: The Social Theory of Magic. It is a “long read” — you may prefer to watch the video of the talk (an hour and a quarter) or to download the podcast! The podcast is a new supplement to The Zen Pagan, which we’ll be experimenting with in the months to come. The video and podcast versions include a discussion portion, not transcribed here.

Why The Moment Calls For Magic

Hi. For those who don’t know me, I’m Tom Swiss. I blog on the Patheos Pagan channel as “The Zen Pagan”, and I’m the author of Why Buddha Touched the Earth. If I’ve counted on my fingers right, this is my twentieth Starwood.

Among my interests are satire and parody religions. I’ve paid to join the Church of the Subgenius, and I’m a Discordian pope (but so are you and everyone on the planet, so that doesn’t mean anything, Hail Eris!) and was in early on Pastafarianism.

So I’ve been interested in the development of the satirical winter holiday Festivus. This came from a 1997 episode of Seinfeld [Burg, Schaffer, O’Keefe], where George Costanza’s family has a holiday celebration that is in part sort of a protest against consumerism, and part just the sort of general awkward weirdness that was the heart of the series.

But as it turns out, there was some serious scholarship about magic in the origin of Festivus.

One of the writers of that episode was Dan O’Keefe, and Festivus was a real family holiday that his father, Daniel Lawrence O’Keefe, originally created to celebrate his first date with his wife.[“Obituary”].

Professionally the elder O’Keefe was known as an editor. He worked at Reader’s Digest (which was a few notches more highbrow at the time) with writers including Ray Bradbury, Ishmael Reed, and Czeslaw Milosz. But he had a PhD in sociology, and a fascination with magical ritual and its place in society. He wrote a book, Stolen Lightning: The Social Theory of Magic, exploring that topic.

Festivus’s origins go back to 1966, and while the aluminum pole wasn’t part of the family celebration, airing of grievances was, and O’Keefe has been recognized as the creator of Festivus. And the family holiday took shape in the 70s, while O’Keefe was doing research for the book.[Salkin]

So I thought it would be worthwhile to check out his book.

It is a dense academic text, full of references to sociologists and anthropologists I’m not familiar with. And written in the 1970s and 80s and based on work decades older, there are some expressions and ideas (Freudian psychology, and expessions like “primitive” man) that ring a little odd today. But his goal is to develop a theory of magic as a social phenomenon, and it’s structured around thirteen interesting postulates about magic:

1. Magic is a form of social action.

2. Magic social action consists of symbolic performances – and linguistic symbolism is central to magic.

3. Magical symbolic action is rigidly scripted

4. Magical scripts achieve their social effects largely by pre-existing or pre-figured agreements

5. Magic borrows symbolism from religion and uses it to argue with religion in a dialetic that renews religion

6. Logically, and in some observable historical sequences, magic derives from relgion rather than vice versa

7. Magic is a byproduct of the projection of society in religion

8. Religion is the institution that creates or models magic for society

9. Magic tries to protect the self.

10. Magic helped develop the institution of the individual

11. Magic – especially black magic – is an index of social pressures on selves and individuals

12. Magic persists as an expression of certain aspects of civilization

13. Magical symbolism travels easily and accumulates history.

Now those ninth, tenth, and eleventh postulates — “Magic tries to protect the self, ” “Magic helped develop the institution of the individual” and “Magic – especially black magic – is an index of social pressures on selves and individuals” are very interesting for the times in which we find ourselves.

As we look at the political situation — the refugee crisis and the the climate crisis, and reactionary or head-in-the-sand responses to them on the right, the fragmentation of the nominal left into factions of performative social media wokeness, violent anti-speech and anti-journalism vigilantism, ineffective centrism, and apologetics for past Democratic sins — those three postulates of O’Keefe’s seem very relevant to why magic is having a pop culture moment, why we’re seeing rituals to curse or block Trump or to protect migrants in detention centers.

But it’s not just a question of the Trump era. We started to get in trouble way back in the nineteenth century, or even back before that at the end of the Middle Ages when the process of “land enclosure” began in England. Over this period we, as a species, started moving from a system of agricultural villages plus the occasional city as a trading post and government center, to most of us living in industrialized cities. Just within the past decade or so, we crossed the threshold where more human beings live in industrialized cities than outside of them.

So I always want to take a broad view of the history — and, brief commercial message, part of my book, Why Buddha Touched the Earth, talks about the Neopagan revival as a response to this industrialization. And you can go buy that book at the ACE tent.

But the point is that when I say that the moment calls for magic, that may be a bit more true that it was four years ago — but it’s not as if everything was okay four years ago and we had no call for magic then.

These are issues we’ve been dealing with for the past few centuries, as we obtained the technological capacity for repression, homicide, and ecocide on an industrial scale — but also, if we become wise, the capacity for healing, housing, and feeding every human being on the planet with sustainable energy and green production systems.

It’s like the cliche about the Chinese word for crisis being made from roots meaning “danger” and “opportunity”. The linguistic part of that isn’t really true[Adams], but the idea spread just beccause it is often a truth about crisis points.

If we want to get through this crisis, we’re gojng to have to bring forth a lot of change. And as Crowley tells us, “Magick is the Science and Art of causing Change to occur in conformity with Will.”[Crowley, Ch I]

And we’re also going to have to, at least for a while, push for those changes against a social structure that has a great deal of energy invested in resisting foundational change — change at the root, which is the literal meaning of “radical”. From heedless unsustainable industrialization to capitalism that makes a handful of people billionaires while others are homeless, to the huge medical insurance industry whose purpose is to collect premiums and deny care…if we’re going to fix this stuff we’re going to have to be rebels for a while.

Anyway. To best address those three postulates it would be best to put it in the framework of O’Keefe’s others. But it’s also my intention today to use them as a jumping off point for a broader discussions.

Magic is a form of social action

Well, what is magic? We can give a dozen different definitions, and they’ll contradict each other to some degree and agree to some degree, and they’ll all be appropriate to some contexts and not to others.

O’Keefe is was not a practitioner of magic, and in this book he doesn’t take a stand on whether “supernatural” or “paranormal” phenomena are objectively real. (Which lines up well with my own take.) Instead he starts with a question rooted in the sociological literature:

This study began with a problem in sociological theory, especially with Durkheim and Weber [two of the founders of sociology as a discipline -tms]. Why did Max Weber use the word magic on almost every page and never define it? What is magic? I got my first lead from two short sections in Durkheim’s impressive study of religion as the worship of society. In thirteen sharp pages it stated that magic is something anti-religious that develops out of religion. Why? In certain writers in the Freudian tradition I saw a hint of an answer: Magic is symbolism expropriated to protect the self against the social.[O’Keefe, xviii]

…

…My deduction: Magic defends the self against society.

What, then, is magic? If religion is the projection of the overwhelming power of the group, and if magic derives from religion, but sets itself up on a somewhat independent basis to help individuals, and is, at the same time, frequently reported to be hostile to religion…then is not the answer apparent? Magic is the expropriation of religious collective representations for individual or subgroup purposes—to enable the individual ego to resist psychic extinction or the subgroup to resist cognitive collapse.[O’Keefe, 14]

And goes on to sketch this outline:

Magic is real action. Something really happens, often something violent, usually something of consequence. People are shaken, influenced, healed, destroyed, transformed. The social situation is altered. Magic is not mere illusion just because its efficacy depends on beliefs in illusory entities.[O’Keefe, 25]

and

Magic actions are rituals that make or change something. They operate mysteriously and what they create is mostly mystical — but these mysterious actions have social effects.[O’Keefe, 28]

and

Magic is often performed on objects, with the action really oriented to the behavior of others. The “objects” have social meaning, the rites and representations are traditional, and other people are involved, at least implicitly. In fact, magic is more often than not collective social action. Solitary-seeming magics such as yoga and mysticism and the study of occult arts also have social objectives: in practice they translate into “withdrawal and return” (Toynbee), the pursuit of power, prestige and authority over others.[O’Keefe, 25-26]

Now, we might push back on that one a little bit; another topic I’ve talked about (this comes from Ronald Hutton) is how 19th century occultism repurposed magical rituals to be a means spiritual development, rather than a means of achieving practical worldly ends as was the case for medieval magic. But I think it holds as a general observation over all of history: humans use magic to seek power.

This idea of magic as a social phenomenon reminds me of some of the ideas of Robert Anton Wilson. In the Illuminatus! trilogy — which is classic psychedelic science fiction, and if you’re the sort of person who comes to Starwood you need to read it — Wilson and co-author Robert Shea explain how magic creates reality in a discussion between the characters Hagbard Celine and Simon Moon , as they wait for the cops and the tear gas in Chicago in 1968:

“Chairman Mao didn’t say half of it,” Hagbard replied holding a handkerchief to his own face. His words came through muffled: “It isn’t only political power that grows out of the barrel of a gun. So does a whole definition of reality. A set. And the action that has to happen on that particular set and on none other.”

“Don’t be so bloody patronizing,” I objected, looking around a corner in time and realizing this was the night I would be Maced. “That’s just Marx: the ideology of the ruling class becomes the ideology of the whole society.”

“Not the ideology. The Reality.” He lowered his handkerchief. “This was a public park until they changed the definition. Now, the guns have changed the Reality. It isn’t a public park. There’s more than one kind of magic.”

“Just like the Enclosure Acts,” I said hollowly. “One day the land belonged to the people. The next day it belonged to the landlords.”

“And like the Narcotics Acts,” he added. “A hundred thousand harmless junkies became criminals overnight, by Act of Congress, in nineteen twenty-seven. Ten years later, in thirty-seven, all the pot-heads in the country became criminals overnight, by Act of Congress. And they really were criminals, when the papers were signed. The guns prove it. Walk away from those guns, waving a joint, and refuse to halt when they tell you. Their Imagination will become your Reality in a second.”

Magic social action consists of symbolic performances – and linguistic symbolism is central to magic

I don’t think we’ll get much disagreement on that. Magical ritual is about manipulating symbols, most especially words. If you don’t think that words have magical power, walk up to someone and say “Fuck you.” Or “Make America Great Again.” Or use the n-word or the c-word or the k-word. Primitive but powerful magic.

But I think it’s useful to call out a point here: everything that uses language is a “social construct”, as the woke like to say. None of us learn or use language on our own. It takes a society to create a language.

Anyway, O’Keefe says:

Something seems to steal a primitive [sic] man’s attention, as if my magic; he is caught and held by the image. When the ego, as a category of the human spirit, was not much developed, intentionality was not sufficiently organized to control attentionality, and men were singularly vulnerable to “fascinations”…[O]ne of the functions of the shaman was to defend smaller vulnerable societies from deadly chain reactions caused by such fascinations. …

Man’s attentionality is especially vulnerable to words since they constitute his species-specific environment….

The magic of words is of the same stuff as the world that made us, and so it can do straight into us…

But magic is not so much these vulnerabilities and effects as it is the use to which they are put. In magic, man concentrates his efforts, gets some control over those phenomena and ultimately over his own attentionality. [Quoting Ernst Cassirer’s An Essay on Man?], “Faith in magic is one of the earliest and most striking expressions of man’s awakening self-confidence. Here he no longer feels himself at the mercy of natural or supernatural forces. He begins to play his own part…”[O’Keefe, 47]

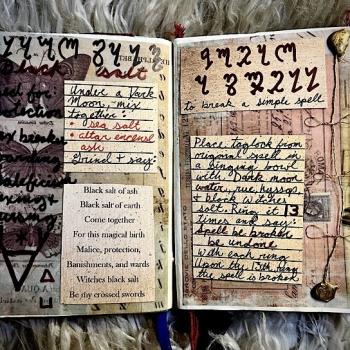

Magical symbolic action is rigidly scripted

As someone whose rituals involve a fair degree of improvisation, I wanted to push back against that a bit. But it is true that those improv rituals are often largely a matter of assembling a set of fixed, scripted pieces chosen in an improvised fashion, and filling in the gaps. And also O’Keefe is trying to look at all of human experience; in most societies throughout history, and probably prehistory, these things are highly scripted.

In O’Keefe’s view, magical speech expropriates it’s “scripts” from religion — chants, incantations, whole frameworks of operation, are yanked out and repurposed. (By “religion”, O’Keefe means “the traditional symbolic projection of the community” — again, this is all from a sociological approach.) And when you have something that your community agrees is powerful, you are really careful about changing it. If you do you’re probably going to break it so it doesn’t work at all, or so it will misfire.

…[S]acred dramas are scripted in a literal sense — the words used in magic and religion are memorized and must be said just right; sometimes they can kill you if they are said wrong.[O’Keefe, 64-65]

Now, here in the Neopagan revival we have an interesting time because some of these scripts are just being written. For example there’s a chant that has come up a few times for me this Starwood, you might know it:

Hoof and horn

Hoof and horn

All that dies

Shall be reborn

Corn and grain

Corn and grain

All the falls shall rise again

The fellow who wrote that chant is right here with us at Starwood — Ian Corrigan, one of the founders and organizers of the festival! (One woman started that chant at the “intentional” fire circle we did the other day, and was really surprised when I told her she knew it’s author — she had learned it at a Rainbow Gathering.)

So new scripts can be written. (Obviously it has to happen from time to time, or there wouldn’t be any to start with!) But if they succeed, if they become important enough to become religious, then they become part of How Things Are Done and become pretty fixed.

Magical scripts achieve their social effects largely by pre-existing or pre-figured agreements

I love watching Ian and Sue do the opening and closing rituals here each year. It’s a master class in magic. What do they always ask? “Is it your will that…blah blah blah.”

Setting intent is the first step in any magical working — as Crowley said, every intentional act is a magical act. And we’re doing any magic that involves more than one person, we have to agree on an intent.

This strikes me as similar to the practice of “yes, and” in improv comedy. If I’m doing an improv scene with someone and they say “Hey, let’s go the circus!”, if I say “Nah,” the scene doesn’t go anywhere. But if I say “Yes! And…we should take some peanuts to give to elephants!”, and they reply “Yes! And…what sort of peanuts should we take for circus elephants? Circus peanuts!”, then we’re on our way to a sketch about giving candy to circus animals who then go hyperactive from the sugar and stampede all over the clown car.

That intent is often pre-existing because of a social agreement about the nature and intent of the ritual. If you come to me for healing work, we already have a good deal of agreement about what’s supposed to happen. An initiation ceremony, a marriage or handfasting, a funeral or wake — we’ve seen these before, we know what’s supposed to happen.

But also, a successful magician persuades us into agreement, by playing on our ideas of identity:

The rhaetor states a premise in a persuasive manner so as to get the people to identify their own inarticulated consensus with his intention. “We all agree,” the speaker says, and then gives his own definition of some principle that sounds close enough to the general will so that the crowd will go along with him. One agreement on the major premise is secured, the conclusion is clinched. I would like to characterize this operation as “a first person singular speaking in the first person plural” and getting away with it. I think this operation is significant for magic…even in real institutional magic, there is often an underlying reasoning in which the major premise is from the religious consensus universe of discourse and slanted; this makes possible the deduction of a magical effect. In magic in the weak sense, persuasion often takes the form of speaking in the management voice before you belong to the management. [O’Keefe, 83]

O’Keefe suggests that magic works through a process of “deviation via a temporary relaxation of the normal social frame of orientation” — we often call that “raising magical energy” — and by “overvaluation and patterning of the resulting experiences by social agreement“[O’Keefe, 96] — or by setting intention, we might say.

It’s why we come to temporary autonomous zones like Starwood, where the usual social frame is…relaxed, to say the least….and we have an agreement that this is a magical space. (If anyone here is new, just let me speak in the management voice for a minute and assure you that this is magick, and if you are here you are therefore a magickian.)

And he points of that the normal frame is really pretty fragile: it’s a social construction itself, and requires attention to sustain it. So it’s inevitable that it’s going to have lapses:

The eruptions of unusual material are not only rationalized by the frame. They also have to be taken over and patterned, for the protection of the paramount reality. Religion has always done this. As the social frame [here he means our social frame] becomes increasingly scientific and the religious frame seems increasingly to detach itself from it and become marginal, the religious frame seems by comparison, in a secular age, to be relatively more preoccupied with these phenomena. But this is in part because religion as the original frame of overarching reality had to protect itself against this chaos by inventing patterns to contain it. Part of the tension between magic and religion is due to the comparatively greater use that magic deliberately makes of frame-relaxing phenomena which religion attempts to control. Churches try to monopolize magic in part because they are always suspicious of these phenomena, even mysticism. The framework of orientation of the religious worldview always remains closer to the frame of the paramount reality, which used to nest within it; whereas magic purposely cultivates paranormal phenomena in experimental act-as-if groups as draft legislation for the creation of frame alterations.

In other words, us magicians are out here running experiments about altering the whole social frame. Which is something we desperately, desperately need to do.

Magic borrows symbolism from religion and uses it to argue with religion in a dialetic that renews religion

The relationship between magic and religion is one of those foundational, definitional arguments, and is a point of contention between different schools of sociology. Did religion develop out of magic, or magic develop from religion? (Or course to some degree it’s a question of how you define those terms.) O’Keefe holds that:

Logically, and in some observable historical sequences, magic derives from relgion rather than vice versa

Magic is a byproduct of the projection of society in religion

Religion is the institution that creates or models magic for society

One point that’s especially relevant to us in the Neopagan revival, as we seek to either revival or borrow from the old ways:

We have plenty of evidence of magic borrowing from older, bypassed, wounded or more primitive [sic] religons. In the ancient world, for example, the magical rites of the mystery cults were in many case borrowed from primitive [sic] rural religions. Magic is, in fact, quite industriously antiquarian. Because magic travels easily, accumulates in cosmopolitan civilizations once committed to writing, is preserved and easily revived in occult revivals, remnants of quite remote religions can persist withing magical amalgams. Religious ideas from other societies often first penetrate a culture as magic (just as the stranger’s religion is always seen as magical). And they persist in a magical afterglow when they are vanquished (just as outlawed religions are condemned as magical). Dead of dying religions are a major source of magic, especially when the stricken cults are denigrated as magical by their successor, the way that Christianity declared the gods of Rome to be demons.[O’Keefe, 123]

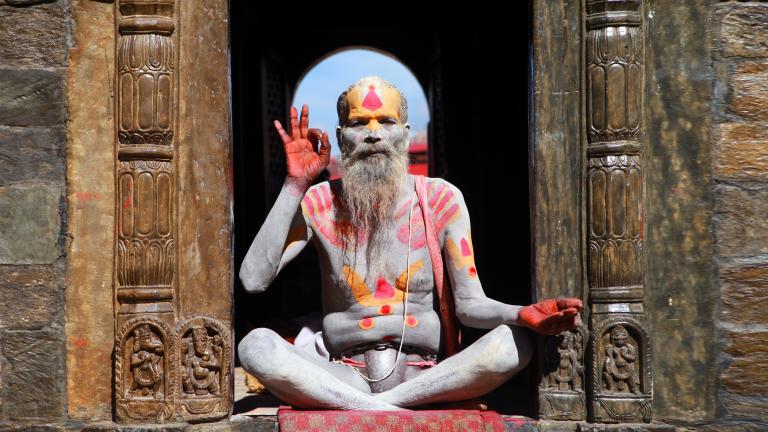

Some of this dovetails nicely with one of the central ideas that has guided my work over the past decade or so, and which I explore in Why Buddha Touched The Earth. This is an observation from Joseph Campbell made in his essay “The Symbol Without Meaning”, where he discusses the difference between shamanistic and priestly religions.

Campbell points out that in gatherer-hunter societies, there is little specialization; individuals typically practice all elements of their culture. While each person has their talents, everyone does everything. That includes religion: the mystical experience is available to all. Even though the tribal shaman was the best at entering that state, anyone might go on a “vision quest”.

But civilized agrarian societies evolved specialization in every field, including religion. Organized priestly religion became a way to resolve humans to their confined, limited roles. Access to mystical states of consciousness was restricted to specialized devotees authorized by the power structure. [Campbell, 142-145; 157-164] Where the distinguishing characteristic of a shaman is their relationship with the spirit world, one can only become a priest via a ritual investiture by the existing power structure.

This is the sort of religion that O’Keefe is referring to as “the projection of the overwhelming power of the group”.

It seems to me this is where the Neopagan revival comes in: an opportunity to build a new sort of religion suitable for that new era, something more in that shamanistic mode, where “priests” are “first among equals” distinguished only by their personal mana and skill rather than investiture by the established hierarchy.

So magic, then, is rebellion. (I’m thinking right now of the end of The Last Jedi, where the First Order thinks it’s stamped out the Jedi and the last remnants of the Resistance, bu we see that slave kid use the Force to sweep the stable…)

Magic tries to protect the self

Magic helped develop the instituion of the individual

By “the self” here, O’Keefe means the psychological self, the inner subjective experience; while “the individual” refers to the objective political/legal/social institution.[O’Keefe, 263]

In O’Keefe’s view, throughout human history magic has served as a form of resistance to the conformity-inducing sort of religion and the hazards it poses to the self. And thus, it seems to me, magic is also suited to a time when we need a political resistance.

In exploring these ideas O’Keefe goes back to Freudianism and psychoanalyis, which usually (but not always) ses magic as infantile, dysfunctional, or regressive. But he finds that these ideas help demonstrate what it is that magic defends against. [O’Keefe, 264]

One of the important ideas here is the idea of “ego death”, that helplessness is ego death and can lead to physical death.

Instead magic — which the psychoanalysts often see as neurosis — offers us the opportunity to connect to the power of the gods. He quotes Wilhelm Stekel:

The life of the compulsive neurotic is but a series of oracles. A small change of posture or of an everyday routine may be good luck or bad luck….By adherence to supersition man endows himself with mystical power. He steals the power of the Deity.[O’Keefe, 276]

Stekel phrases this negatively, but it matches well with how Crowley saw communications from the “Secret Chiefs”:

These powers move in dimensions of time and space quite other than those with which we are familiar. Their values are incomprehensible to us. To a Secret Chief, wielding this weapon, “The nice conduct of a clouded cane” might be infinitely more important than a war, famine and pestilence such as might exterminate a third part of the race, to promote whose welfare is the crux of His oath, and the sole reason of His existence!

…

They may send an ordinary living man, whether one of Themselves or no I cannot feel sure, to instruct me in some task, or to set me right when I have erred. Then there have been messages conveyed by natural objects, animate or inanimate.† Needless to say, the outstanding example in my life is the whole Plan of Campaign concerning The Book of the Law. [Crowley, Ch IX]

I’m also reminded here of the Discordian Law of Fives: Everything happens in fives, or multiples of five, or is in some way connected to the number five. And the harder you look, the more you will find this to be true. Let me repeat: the harder you look, the more evidence for this you will find.

Just so, if you decide that your life is magic, that you are touched by the deities or the fay folk or the spirits of the ancestors, then the harder you look, the more evidence for this you will find.

So magic gives us the power to believe that we, individually, are important. In that, we might say that magic (this sort, at least) is anti-fascist — after all, one of the key tenets of fascism is that the individual is weak, only the group (other than the Glorious Leader) matters.

I think it’s also worth noting that Hunter S. Thompson (and gods, how I miss him) said that politics the art of controlling one’s environment.[Thompson, 17] Words like “empowerment” and “agency” come to mind.

O’Keefe quotes anthropologist-psychoanalyst Gèza Róheim’s Magic and Schizophrenia:

We grow up through magic and in magic…Our first response to the frustrations of reality is magic; and without this belief in ourselves…we cannot hold our own against the environment and against the superego…In magic, mankind is fighting for freedom.[O’Keefe, 334-5]

Magic – especially black magic – is an index of social pressures on selves and individuals

…[B]lack magic springs up when either the self or the Individual is stressed, even in modern times[O’Keefe, 414]

He starts with an interesting idea about how accusations of witchcraft might have originated in early societies. Rejection by the group in such cultures can lead to death, either through psychosomatic illness (“voodoo death”), or execution, or by being cut off from basic necessities such as food, shelter, fire, etc. And as there isn’t a lot of hierarchy there, most anyone can speak with the “management voice” under the right circumstances — and that voice can kill.

What attacks the guilty person is the moral force of society; but this force is always personified in an individual who speaks on its behalf. Howard Becker calls suck a person a “moral entrepreneur.” (Malinowski showed how his moral initiative could force a Trobriander to kill himself.) Among very primitive [sic] peoples, the moral entrepreneur’s power will perhaps be conceptualized as a totem. It is an easy step from this to suppose that the guilty person may imagine that his critic has sent his totem animal to attack him–and this would certainly help explain why witch beliefs [we’re not talking Wicca here, obviously] all over the world include the idea of the witch sending her familiar to attack her victims in the night. The man condemned to die by group morality may indeed, during the throes of that “killer anxiety” or “disorganizing depression” or whatever the precise process of voodoo death is, that he is being destroyed by a bat or black cat or a werewolf or some other totem whose taboo he infringed, or the totem representing the clan he offended, or the personal totem of the person who criticized him.[O’Keefe, 418]

And then accusing the accuser of witchcraft for these attacks becomes a means of defense:

…the accusation of witchcraft is the magical act, perhaps the earliest and most primitive magic, in which an individual escapes voodoo death by turning the tables on a moral entrepreneur who is putting superego pressure on him. Someone says you are violating the group morality; this could kill you in a primitive strategy. But instead you accuse him of being a witch, of being the very opposite of every value the group stands for, and this may save your life.[O’Keefe, 415]

We tend to take the witch hunts of Europe and colonial America as our model, where the accused were people of low status — in Tudor England, the poor were accused to witchcraft just as land enclosure and capitalism were getting going, and this helped force the end of right of the commons and bring on the revolution of privatization. (Not all revolutions are good, it needs to be noted.) But accusations of witchcraft are used against the powerful in other societies. It’s been seen in some African societies where chiefs and headmen are accused of witchcraft as a means of making even the powerful obey the rules.[O’Keefe, 437]

So there are some interesting power strategies here — imagine some religious right type attacking your rights, and you turn the tables by accusing them of witchcraft.

How does black magic then become an index of social pressure?

When the determined world suddenly reveals itself as not determined, Sartre wrote, the recognition my be experienced as horror. [Consider the horror many Democrats experienced when they learned that the “determined world” in which Clinton was going to win turned out to not be so determined. -tms] The effect may be regressive. Individuals may become suspicious, inclined to wonder, like primitive [sic] man, “who” is doing it, instead of “what” is doing it. Conspiratorial theories then abound [consider Q-Anon to Russiagate -tms], and what Hofstadter calls “the paranoid style” may prevail in politics as institutions are suspected of being less solid than they seem. Then “each thing meets in mere repugnance” (Coriolanus) and homo homini lupus [“Man is wolf to man”] implies that every man is also a sorcerer. Then desperate men try to regain their magical powers, first through status symbols, later through mystifications and deceit, but [and this is important as we magicians decide what magic to work! -tms] such attempts are confessions of weakness and vulnerability, rather than of strength, and they aggravate social conflict.[O’Keefe, 448-449]

Magic persists as an expression of certain aspects of civilization

How is it that magic persists? There must be something about the social situation that drive us to it:

…[M]agic may be the natural projection of advanced “organic solidarity” (society held together by division of labor). Today post-industrial society, in splitting the “formal rationality” of its complex systems off from the “substantive rationality” of individuals, makes the world seem uncanny to the self….”magical thinking” is the only way of coping when the world becomes (or seems) demonic….

…Perhaps the occult is the natural expression of a society in which we live surrounded by machines, bureaucrats, technologies, and planning systems made by human rationality but unfathomable to us personally.[O’Keefe, 458]

Magical symbolism travels easily and accumulates history

And as an underground force, magic can never be stamped out:

Magic is a bookish business and always has been since writing was invented. The grimoires of the Middle Ages, the voluminous publications of the alchemists, the dream books of the ancient world pour forth like a torrent, and few titles are every permanently lost. There are eras when magic is quiescent, but the accumulated tradition is kept alive by antiquarian or eccentric interest, by underground cults, by the Vatican library, or the Warburg Institute in London, or the secret societies or each era’s equivalent of New York’s Sixth Avenue in the forties:

The occult is rejected knowledge: that is, an Underground whose basic unit is that of Opposition to an Establishment of Powers That Are. [O’Keefe is quoting James Webb, The Occult Underground, 1974]

…Again and again magic belief is renewed when someone goes to the library and consults the tradition.

So protect those libraries!

References

Adams, Cecil. “Is the Chinese word for ‘crisis’ a combination of ‘danger’ and ‘opportunity’?” The Stright Dope. 3 Nov 2000.

https://www.straightdope.com/columns/read/2363/is-the-chinese-word-for-crisis-a-combination-of-danger-and-opportunity/

Burg, Alec; Jeff Schaffer; and Dan O’ Keefe. “The Strike” Seinfeld http://www.seinfeldscripts.com/TheStrike.htm

Campbell, Joseph. “The Symbol Without Meaning.” The Flight of the Wild Gander. New York, N.Y: HarperPerennial, 1990.

Crowley, Aleister. Chapter I: What is Magick? Magick Without Tears https://hermetic.com/crowley/magick-without-tears/mwt_01

Crowley, Aleister. Chapter IX: The Secret Chiefs. Magick Without Tears https://hermetic.com/crowley/magick-without-tears/mwt_09

O’Keefe, Daniel Lawrence. Stolen Lightning: The Social Theory of Magic. New York: Vintage Books, 1983.

Obituary. O’KEEFE–Daniel L., New York Times. 17 Sep 2012. https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/nytimes/obituary.aspx?n=DANIEL-OKEEFE&pid=159946083

Salkin, Allen. “Fooey to the World: Festivus Is Come.” New York Times. 19 Dec 2004. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/12/19/fashion/fooey-to-the-world-festivus-is-come.html

Thompson, Hunter S. Better Than Sex: Confessions of a Political Junkie. New York: Random House, 1994.