It has been the fashion among the pundit class for a while now to decry the death of expertise. The first rumblings go back almost a decade, but the complaints have accelerated in the past few years:

Blogs have become so dizzyingly infinite that they’ve undermined our sense of what is true and what is false, what is real and what is imaginary. These days, kids can’t tell the difference between credible news by objective professional journalists and what they read in joeshmoe.blogspot.com. For these Generation Y utopians, every posting is just another person’s version of the truth; every fiction is just another person’s version of the facts. — Andrew Keen, Silicon Valley entrepreneur and media critic, The Cult of the Amateur, 2007

There is no better example of the death of expertise than Jenny McCarthy. A television personality and ex-Playboy centerfold with zero medical training who nonetheless has become an autism expert, after her son was diagnosed with the malady. McCarthy—who was recently hired by ABC to co-host their daytime talk show “The View”—claims that vaccines trigger autism. Despite the fact that the central study promoting this view has been thoroughly discredited and the author stripped of his medical license, McCarthy has doubled down on her anti-vaccination claims and remains the celebrity ambassador to the vaccine-questioning autism organization Generation Rescue. According to a University of Michigan study, almost one-quarter of American parents put “some trust” in the medical advice given by celebrities like her. — Jessica Grose, writer and editor, “Please, Pinterest, Stop Telling Me How to Repurpose Mason Jars”, The New Republic, 2013

I fear we are witnessing the “death of expertise”: a Google-fueled, Wikipedia-based, blog-sodden collapse of any division between professionals and laymen, students and teachers, knowers and wonderers – in other words, between those of any achievement in an area and those with none at all. By this, I do not mean the death of actual expertise, the knowledge of specific things that sets some people apart from others in various areas. There will always be doctors, lawyers, engineers, and other specialists in various fields. Rather, what I fear has died is any acknowledgement of expertise as anything that should alter our thoughts or change the way we live. — Tom Nichols, professor of National Security Affairs at the U.S. Naval War College, “The Death Of Expertise”, The Federalist, 2014

Increasingly, expertise, and the role of “the expert” is losing the respect that for years had earned it premiums in any market where uncertainty was present and complex knowledge valued. Along with it, we are shedding our reverence for “expert evaluation,” resigning our regard for our Michelin guides and casting our lot with the peer-generated TripAdvisors and Yelps of the world. — Bill Fischer, professor of Innovation Management at IMD, “The End of Expertise”, Harvard Business Review, 2015

Now we cannot deny that there are some areas where Americans are rejecting the well-informed conclusions of experts in a problematic manner. The way that so many people believe in the debunked relationship between vaccination and autism is one example; climate change denialism is another.

But in many instances what is being rejected is not actually expert opinion but the opinion of courtiers.

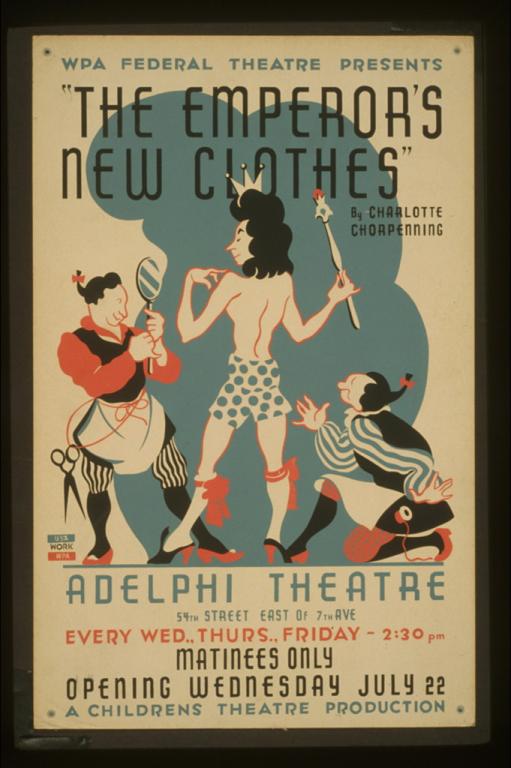

I mean “courtiers” here in a sense generalized from PZ Myers use in “The Courtier’s Reply”. Myers coined the term to refer to a specific variety of ad hominem attack; in his original usage he likened Richard Dawkins’ book The God Delusion to the boy who revealed the Emperor’s nakedness in the fable, and compared critics who attacked Dawkins’ lack of credentials in theology to an imagined courtier denying the Emperor’s nakedness by appeal to haute couture:

I have considered the impudent accusations of Mr Dawkins with exasperation at his lack of serious scholarship. He has apparently not read the detailed discourses of Count Roderigo of Seville on the exquisite and exotic leathers of the Emperor’s boots, nor does he give a moment’s consideration to Bellini’s masterwork, On the Luminescence of the Emperor’s Feathered Hat. We have entire schools dedicated to writing learned treatises on the beauty of the Emperor’s raiment, and every major newspaper runs a section dedicated to imperial fashion; Dawkins cavalierly dismisses them all. He even laughs at the highly popular and most persuasive arguments of his fellow countryman, Lord D. T. Mawkscribbler, who famously pointed out that the Emperor would not wear common cotton, nor uncomfortable polyester, but must, I say must, wear undergarments of the finest silk.Dawkins arrogantly ignores all these deep philosophical ponderings to crudely accuse the Emperor of nudity.

…

Until Dawkins has trained in the shops of Paris and Milan, until he has learned to tell the difference between a ruffled flounce and a puffy pantaloon, we should all pretend he has not spoken out against the Emperor’s taste.

— PZ Myers, The Courtier’s Reply”, Pharyngula, 24 Dec 2006

To expand on Myers’ metaphor, a courtier is one who possesses socially-recognized authority and peer-accepted knowledge, but that knowledge and authority is based on socio-political power structures rather than empirical reality.

And we have been suffering a plague of courtiers for years.

They’ve been a problem in the academic humanities for decades. As John Brockman noted in 1991, “[T]he traditional American intellectuals are, in a sense, increasingly reactionary….Their culture, which dismisses science, is often nonempirical….It is chiefly characterized by comment on comments, the swelling spiral of commentary eventually reaching the point where the real world gets lost.”

Alan Sokal gave a definitive demonstration of the problem in 1996 when he submitted a paper of absolute gibberish, “Transgressing the Boundaries: Toward a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity”, to the journal Social Text. They fell for it hook, line and sinker.

Sokal later wrote, “The editors of Social Text liked my article because they liked its conclusion: that ‘the content and methodology of postmodern science provide powerful intellectual support for the progressive political project.’ They apparently felt no need to analyze the quality of the evidence, the cogency of the arguments, or even the relevance of the arguments to the purported conclusion.”

Unfortunately the problem has not gone away since Sokal’s hoax. Steven Pinker noted in 2013,

The humanities have yet to recover from the disaster of postmodernism, with its defiant obscurantism, dogmatic relativism, and suffocating political correctness. And they have failed to define a progressive agenda. Several university presidents and provosts have lamented to me that when a scientist comes into their office, it’s to announce some exciting new research opportunity and demand the resources to pursue it. When a humanities scholar drops by, it’s to plead for respect for the way things have always been done.

But if courtiers in the academic humanities are a problem, that’s only more true by an order of magnitude when they obtain political power.

Our aggressive and stupid foreign policy is a creation of courtiers, a product of a self-reinforcing orthodoxy untainted by facts or critical thinking. The same is true of our carceral state. It is courtiers, not experts in criminal justice, who tell us cops are justified when they shoot unarmed black men. It is courtiers, not experts in economics, who proclaim that the economy is doing fine despite the stagnation of real wages and the hollowing out of the middle class.

And certainly the election itself was a naked emperor moment for the Democrats and their allies in the mainstream media, who assured us of the certainty of a Clinton victory. Since then numerous stories have emerged of local party activists being ignored by the national Clinton campaign — the campaign’s experts were confident in their models and didn’t listen to empirical data coming in from the field.

They were as sure of their polling and their tactics as Myers’ courtier is of the feathers in the Emperor’s hat.

As the pundits tell us that the election of Trump (which is a horrible thing, don’t mistake me — but possibly in the long run the lesser of two horrors) marks a rejection of “expertise”, perhaps we all should consider what “experts” said about the likely outcome of the election, and think carefully about whether popular pundit wisdom might be as wrong in other areas.

If we can do that, then the end of “experts” might just lead to a rebirth of critical thinking.

You can keep up with “The Zen Pagan” by subscribing via RSS or e-mail.

What Does It Mean For The Gods To Exist? and other essays is now available as a free e-book! It collects my run on the Patheos Agora blog plus a few bonus pieces.

If you do Facebook, you might choose to join a group on “Zen Paganism” I’ve set up there. And don’t forget to “like” Patheos Pagan and/or The Zen Pagan over there, too.