Imagine that we could hop in our TARDIS and jump back to the Golden Age of Athens to grab a musician — say, a lyre player — and bring them forward in time to talk with a modern musician — say, a guitarist.

Let’s call our lyre player Alcaeus, and our guitarist Betty. (And let us assume that our TARDIS handles the language problem as it does for the Doctor and his/her companions.) Alcaeus might marvel at the concept of a fingerboard and frets, while Betty might be amazed at what Alcaeus could accomplish on a few open strings by skillful picking and muting. They would have different ideas about scales and consonant and dissonant intervals; Betty might always sound a little out of tune to Alcaeus’s ears, trained long before the invention of equal temperament. But with a little patience they could have a fascinating jam session.

There’s a good chance that Alcaeus would believe in the literal existence of Apollo and of the Muses. He might well believe that when he was playing at his best, one of these supernatural beings was “playing through his hands” in a literal sense. Betty, on the other hand, might be a hardcore atheist and a metaphysical materialist who believed that what she played was part of the universal dance of atoms, forged in the Big Bang and in the death throes of stars, moving to the melodies of the four fundamental forces.

Their metaphysical views about music might be completely irreconcilable, but they could still play music together.

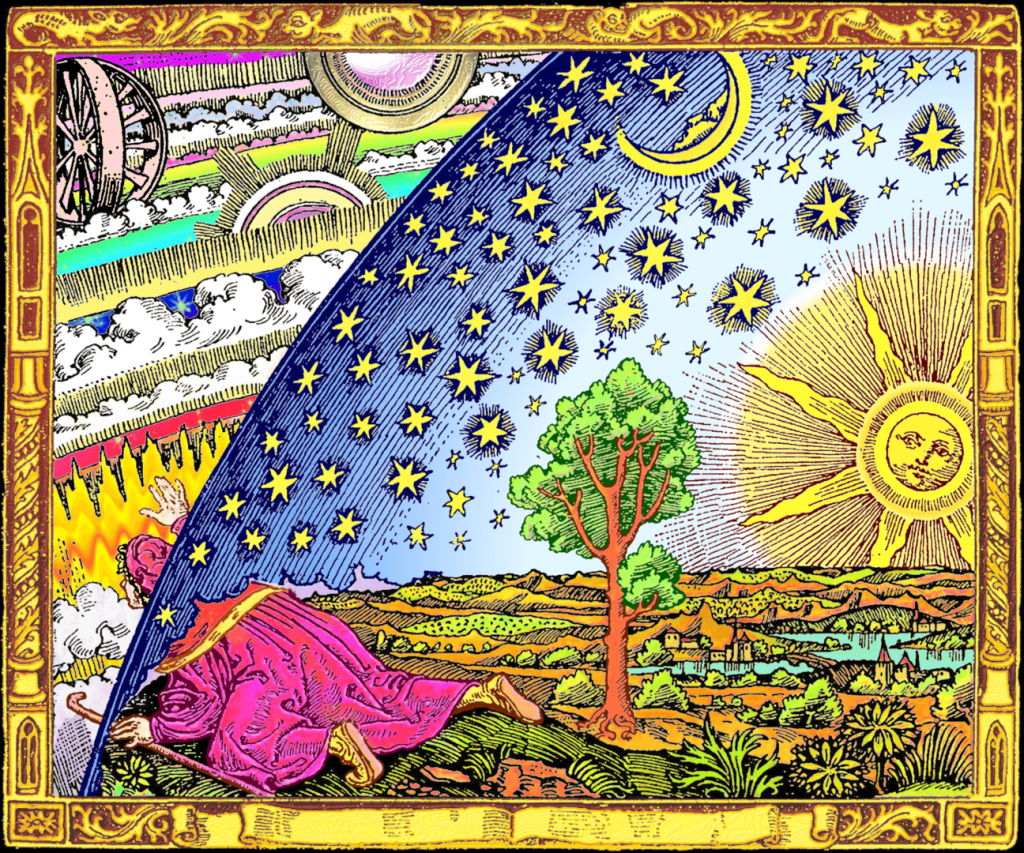

Consider now two people performing a magical ritual together. Charlene may believe that certain words and actions have power because the get the attention of supernatural entities made of some substance not subject to the limitations of ordinary matter, and influence them to do as she asks. Dave may believe that magical ritual is “poetry in the realm of acts”, in Ross Nichols’s lovely phrase, and that such poems have power in the world because they influence humans, who are part of the same dance of atoms that constitute Betty’s metaphysics.

If a non-supernaturalist take like Dave’s seems outside of the Western occult tradition, consider what MacGregor Mathers and Aleister Crowley wrote in a preface to their version of The Lesser Key of Solomon:

…What is the cause of my illusion of seeing a spirit in the triangle of Art?

Every smatterer, every expert in psychology, will answer: “That cause lies in your brain.”…

The spirits of the Goetia are portions of the human brain.

…

If, then, I say, with Solomon:

“The Spirit Cimieries teaches logic,” what I mean is:

“Those portions of my brain which subserve the logical faculty may be stimulated and developed by following out the processes called ‘The Invocation of Cimieries.’”And this is a purely materialistic rational statement; it is independent of any objective hierarchy at all….

…

…There is no effect which is truly and necessarily miraculous.

Our Ceremonial Magic fines down, then, to a series of minute, though of course empirical, physiological experiments, and whoso, will carry them through intelligently need not fear the result.

Now my point here is not to argue that such a metaphysics is better than a supernaturalist one. The point is that when we work magic as communities, we can work the art of magic together with those of a different metaphysical bent — just like Alcaeus and Betty could play beautiful music together.