Why does Les Miserables move me so much?

In 2014, I watched an incredible Broadway performance of that famous musical. By the end, I stood cheering and applauding. I was also weeping openly. Why? I don’t cry that easily–and I know the story extremely well. I’ve even read the book from upon which the musical and the many movie versions are based: all 530,982 words, or 1488 pages of it.

But I still wept.

What I see here each time is the universal story: the grinding, soul-destroying poverty and injustice that rules the lives of most; the occasional ray of light that reminds us that God is indeed present; the power of compassion and the freedom that forgiveness offers; the courage it takes to stand firm, face our enemies and own our identities; and the delight of romantic love.

All there–to beautiful, memorable music that fills heart, mind, and soul.

The most interesting character is Javert, the relentless, righteous one who insists that once a thief, always a thief. He cannot open his mind or heart to any extenuating circumstances. Right is right; wrong is wrong; compassion has no power to move. And ultimately, forgiven freedom makes no sense.

The idea of forgiven freedom is also what has often been termed, “the scandal of the Gospel.” The Gospel, that message often dismissed as “crazy nonsense,” the good news, the extravagant grace, the sweeping away of barriers, is the open invitation into the heart of God.

That scandalous gospel means no piles of laws or endless restrictions, no mediators between God and us, just messengers, those who have seen and now come back to invite others. Instead of having to make ourselves perfect to enter, we enter in all our imperfections and are slowly molded, shaped and refined into the perfection of love, into those who are the healers of the world.

That scandalous gospel means no piles of laws or endless restrictions, no mediators between God and us, just messengers, those who have seen and now come back to invite others. Instead of having to make ourselves perfect to enter, we enter in all our imperfections and are slowly molded, shaped and refined into the perfection of love, into those who are the healers of the world.

But Javert would and could have none of this. His world insisted on perfection before redemption. The opposite idea, so clearly shown in Les Miserables, that forgiveness and release come first and then perfection slowly appears, brought chaos to his ordered world.

I am coming to the conclusion that the drive for perfection fights the possibility of becoming the recipient of grace to the death. It did for Javert–he found death preferable to having to change his understanding of righteousness.

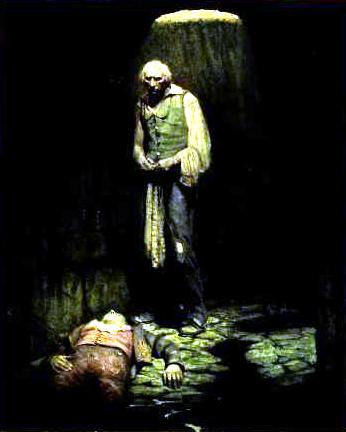

However, for Jean Valjean, the flawed, beaten-up, almost animal-like creature we encounter at the beginning, grace sent him to his knees. He had stolen silver from the Bishop, the only person to show him kindness. When arrested and returned, the Bishop insists he gave the silver to Valjean. Then he takes two large silver candlesticks, and stretches them out to the miserable man and sings,

But remember this, my brother

See in this some higher plan

You must use this precious silver

To become an honest man

By the witness of the martyrs

By the Passion and the Blood

God has raised you out of darkness

I have bought your soul for God!

“I have bought your soul for God.” Possibly the most beautiful line in this exquisite musical. For Jean Valjean received the gift of grace. But not without a hard, honest look at his soul:

What have I done?

Sweet Jesus, what have I done?

Become a thief in the night,

Become a dog on the run

And have I fallen so far,

And is the hour so late

That nothing remains but the cry of my hate,

The cries in the dark that nobody hears,

Here where I stand at the turning of the years?

After recounting the history of his sad life, Valjean concludes:

I am reaching, but I fall

And the night is closing in

As I stare into the void

To the whirlpool of my sin

I’ll escape now from the world

From the world of Jean Valjean

Jean Valjean is nothing now

Another story must begin!

Yes, another story must begin. And that’s the universal power of this musical: all of us want another story to begin.

PS: if you have not seen this video of one musical family singing One Day More, don’t miss it.

Photo Credits: Valjean with Marius, Wikimedia commons; Cossette: Wikimedia commons