Mysterious practices, multiple entrances, confusing requirements, authority figures dressed differently with clothing often suggesting power and authority: hospitals and churches have these in common.

Another commonality: Both seek to move people from one level of existence to another. From physical illness to health, from unredeemed sinner to saint. And both encounter much resistance on the part of humanity: most resist the hard work of forming and practicing the disciplines necessary for healthy body and healthy souls.

These thoughts danced in my head after three days of intensive tests, physical and psychological, as I seek to donate a kidney to my brother. All took place at UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles, CA, one of the top five US transplant hospitals. Hands-down, the number one center on the west coast.

My brother lives near, so it was an easy choice, but a hard system to break into. Just as there are often demanding requirements for church membership, there are also demanding requirements to enter the living donation program. No sense in going through the expense of clearing a donor for a specific recipient until the recipient is cleared as a qualified candidate for a transplant.

My brother went through extensive pre-testing late summer before he began his series of qualification appointments. Final approval came In September.

My process began. First, a giant blood draw, done in Texas and shipped to UCLA for analysis. Same blood type and 50% compatibility make me a good possible donor.

Normally, potential donors have a series of appointments at UCLA spaced by weeks. However, to minimize travel expenses and time away from work, out-of-town donors are treated differently. All appointments are crammed into three days.

And I do mean crammed. Multiple nearly back-to-back appointments ranged from blood and kidney function tests to chest x-rays to educational sessions to evaluations by a social worker and a psychiatrist to sessions with physicians and finally the transplant surgeon.

Many of my friends have jokingly (I think!) wondered what a psychiatrist would do with me. His job was to determine my level of intellectual functioning just in case I sense post-surgical decline in that area. At the end of our interview, he announced, “You are a very bright woman.” It took much self-control not to answer, “I could have told you that and saved us both a bunch of time.” But I managed to refrain.

At the end of the second day of appointments, which had started at 5:15 am, my brother joined me at the convenient on-campus hotel where I stayed. He brought his wife, another good friend, snacks and makings for excellent margaritas. In the relaxed conversation that followed I mentioned how well I’d been treated all day. Few waits, an apology if one occurred, friendly receptionists, and people going out of their way to guide me through the maze of buildings I had to navigate when walking from one appointment to the next.

My brother’s response: “Yes, this is a well-run hospital. More importantly, donors are rare and precious and very much honored here. They appreciate you and want to do everything possible to make this a pleasant experience.”

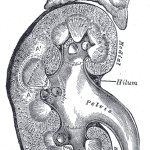

Pleasant as they sought to make it, my last two appointments delivered some difficult news. By then, most test results were already in–pretty impressive, by the way. As I expected, they affirmed that I am in simply excellent health except . . . one test indicates I may be in the beginning stages of my own journey into kidney failure.

We all hope this is an anomaly–possibly simple dehydration from having flown the day before as it generally takes me a while to rehydrate after flying. A definitive answer will come in a few weeks after follow-up testing in Dallas.

I ask for your prayers–and for your greater awareness of the transplant situation. In southern California, a person placed on the transplant list has an average wait for a cadaver kidney of five to seven years. My brother was told to expect a ten year wait for his blood type. Obviously, there exists a huge need healthy living donor kidneys. Buying and selling of kidneys has become a common practice of parts of the world, but is fortunately illegal in the US.

The decision to donate carries absolutely no physical benefit to the donor and carries some risk. Full recovery: six to eight weeks, although most can go back to work sooner. Obviously, the call to donate only comes to a few. But if you sense you are one of those called, you could be giving life to another.

FYI: should a donor face later kidney failure, he/she is automatically placed at the top of the transplant list.

The people of God to be live-givers in every possible way. If this might be your way, let’s talk.