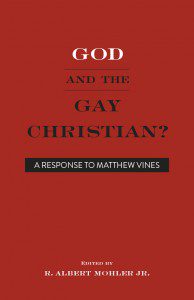

Led by President R. Albert Mohler, Jr., faculty from The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary just published an eBook titled God and the Gay Christian? in response to a new book by Matthew Vines entitled God and the Gay Christian (published by an offshoot of Multnomah/WaterBrook, a historically evangelical publisher).

Led by President R. Albert Mohler, Jr., faculty from The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary just published an eBook titled God and the Gay Christian? in response to a new book by Matthew Vines entitled God and the Gay Christian (published by an offshoot of Multnomah/WaterBrook, a historically evangelical publisher).

I was blessed by the work of faculty colleagues Jim Hamilton (on the OT), Denny Burk (on the NT), and Heath Lambert (on counseling) in this project. Scholarship has immense value when done with the right end and attitude, and these brothers show that in their chapters. The total page count is less than 100, and the text is readable and pastoral.

I strongly commend this SBTS eBook to a wide range of readers. Vines’s book is not dense in terms of scholarship. Hamilton and Burk catch numerous exegetical flaws and errors in his argumentation that their facility with their original languages allows. Indeed, one sees the strength of a program of scholarship in comparing the two books. Vines is a smart person, but he has no formal theological credentials. Hamilton and Burk are able to offer numerous critiques that Vines’s book cannot treat. His book, God and the Gay Christian, is not simply an exercise in false teaching, but an exercise in hubris. At one point, he pats Paul on the back for being good-hearted but behind the times on gender roles. The arrogance of this twentysomething young man with no theological training, lecturing an apostle on his ethics, takes your breath away.

Though it is seriously lacking in exegetical facility, Vines’s text does, however, thread together arguments in crafty and deceptive ways. His book, for example, is not intended simply to legitimize homosexuality, but to wholly discredit complementarians. This is a book that theologians, pastors, laypeople, and many others need to know about. SBTS’s God and the Gay Christian? will help immensely along these lines. This was our goal: to refute false teaching and enable believers to correctly handle the word of truth (2 Timothy 2:15).

Below is a section from my chapter on the church’s historical perspective on homosexual behavior. In this passage, I seek to show that though the term “orientation” is new, the concept of ongoing same-sex attraction and practice is not. Contra what Vines says, neither homosexual practice nor what could be called homosexual “orientation” is approved of or legitimated in biblical doctrine.

The term “orientation” is recent, but Christians have called incidental or regular homosexual practice sinful for millennia. Commenting on Romans 1:27, fourth-century pastor Ambrosiaster traced the root of homosexual sin to “contempt of God.” Those falling into homosexual passion “changed to another order and by doing things which were not allowed, fell into sin” — sin so destructive that it “deceives even the devil and binds man to death.” It is hard to see anything but biblically justified condemnation of homosexuality in these words, whether as a discrete act or a fixed state of lust.

Preaching on this same passage, Chrysostom concluded of those who practiced homosexuality that “not only was their doctrine satanic, but their life was too.” This passage is of particular note, because Vines cites a portion of it (106), but he leaves out this section, claiming only that Chrysostom condemned “excessive” lust. This is no new argument (indeed it is a well-worn one). Vines’s contention suffers not merely from a common misreading of Romans 1, but from a failure to cite properly Chrysostom’s homily. Both the “doctrine” and the “life” of those who abandoned “what is according to nature” — i.e. those who embraced homosexual behavior — should be considered “satanic.” There is no stronger term by which one may identify sin than that.

Chrysostom’s words from the fourth century are instructive and reflective of the broader Christian moral tradition of the past two millennia. For him and countless others of orthodox fiber, homosexual behavior cannot be considered as an isolated act unrelated to moral concerns. The heart that willingly indulges in such behavior is thoroughly sinful. There can thus be no abstraction of practice, as Vines strains to prove. If it is wrong to get drunk, then it is wrong to be oriented (whatever this means precisely) toward drunkenness. If it is wrong to commit pedophilia, then it is wrong to be oriented toward pedophilic acts. If it is wrong for a husband to harm his wife physically, then it is wrong to be oriented toward doing so. There cannot be what Vines calls a “loving expression” of these and any other sins.

Believers still dishonor God after our conversion, but we no longer find our identity in our sin, as Vines wants to do. Indeed, one wonders whether the “coming out” experience of “gay Christians” is more of a conversion than their profession of faith.

For the truly repentant, our identity is in Christ, and we have left behind our wicked practices and our former identities, becoming by the grace of God a “new self” in Jesus (Col 3:10).

Read the whole eBook, which is free.

It is my hope that Matthew Vines and all who make arguments similar to his will repent, trust Jesus, and turn to Christ. We are all disordered and corrupted by the fall of the first Adam. We must all be made right by the second Adam. Though I recognize a range of usage among fellow believers, there is no more category for a “gay Christian” than there is a “wife-beating Christian” or a “pedophilic Christian” or an “alcoholic Christian.”

There is, however, a rich and teeming category of people who are known as “Christian,” for the old has passed away in Christ, and the new has come.