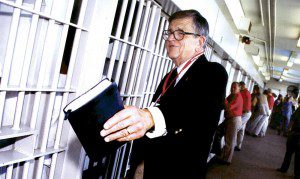

Many years ago, Chuck Colson was doing what he did constantly: visiting prisoners. Formerly incarcerated due to his connections to the Watergate scandal of the early 1970s, Colson became a Christian in 1975 and soon after found his life’s calling: ministering to prisoners.

Many years ago, Chuck Colson was doing what he did constantly: visiting prisoners. Formerly incarcerated due to his connections to the Watergate scandal of the early 1970s, Colson became a Christian in 1975 and soon after found his life’s calling: ministering to prisoners.

In 1985, Colson visited a North Carolina prison. As noted, this was not unusual. What was unusual about Colson’s visit, however, was that a prison chaplain had asked Colson to visit a much-feared prisoner in isolation. This prisoner, a woman named Bessie Shipp, was not in isolation for attacking guards or smashing windows. She was enfeebled. But the prison staff was scared of her, as were most visitors. The reason was simple: Bessie had AIDS. In an era when rumors flew about catching the HIV virus from toilet seats and handshakes, Bessie was placed in a ward by herself. She was alone, frightened, and dying.

I am writing a book about Colson, and so I am accustomed to stories of his remarkable kindness and courage. No anecdote, however, trumps this one. As quoted by Jonathan Aitken in his illuminating biography of Colson, Colson initially felt “absolute terror” at the prospect of going into Bessie’s cell. But he could not hold back. He had seen images of Mother Theresa hugging AIDS patients earlier, and he resolved to do the same. He entered Bessie’s cell, embraced her, and talked with her about the forgiving grace of God. As Colson often did, he connected immediately and deeply with this woman with whom he had little in common. The world was afraid of her twice-over: she was a thief, and she was unclean. But the world’s fears and prejudices are no match for the gospel of Christ and the sinners claimed by it.

Later, Colson wrote a letter to the governor of North Carolina appealing for clemency. The pardon was granted and Bessie left the prison. She did not return to her life of drug-fueled crime. She preached the gospel and told of Colson’s compassionate action. She was on fire for Jesus.

But she was not long for the world. Soon after her release, she became critically ill. In the hospital, she told visitors she was fully at peace with her God. But she clung to one request: she wanted to be baptized. The logistics were nightmarish with her tubes and devices, but Baptists are not easily deterred from their baptizing ways. Bessie was baptized right beside her hospital bed. Though barely conscious, she was at peace. Hours after she passed through the waters of judgment, she slipped away from this world.

Among the countless gripping testimonies that trailed Colson’s ministry, this story grabbed me because it speaks more broadly to the relationship between the evangelical church and AIDS. There surely have been many missteps on the part of American evangelicals in their handling of the disease. But while the “Moral Majority” is often typecast today, leaders like Colson have shown the church and a watching world that one need not sever moral witness from sacrificial generosity. This was true on a much broader scale with PEPFAR (The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief), the foreign policy ne plus ultra of George W. Bush’s presidency. Though imperfect, evangelicals like Bush and Colson have left a mark on the fight against AIDS, whether on a personal or governmental level.

Few of us can pull the levers like the U. S. President. One can hope, however, that the light will not die out. Evangelicals should continue to advocate and sacrificially work to eliminate AIDS. The task is large, even foreboding. But this has not stopped biblically-inspired people before. Christ promised us a kingdom that would suffer violence but never stop advancing (Matt. 11:12). So the story has gone. Telemachus ended the gladiatorial games. Wilberforce took on the slave trade, and vanquished it. Bonhoeffer, very nearly alone, dared to stand up to Hitler and his thousand-year Reich. King faced down tyrannical Jim Crow and sent him packing. This is a diverse group with diverse views, but these and countless other figures fired by the example of the ancient prophets have dared to stand up against evil and suffering and injustice.

Modern evangelicals who love the prophets of old and who savor a cruciform salvation have no other option but to act in this way. Fighting–and defeating!–AIDS is a monumental task. But our will should not waver on this count. With friends from all over the spectrum, we should keep our hand to the plow. We should pray and agitate and form policy and lobby people and take missions trips and–in sum–act in love to seek to end the suffering that AIDS causes.

As we do so, we should remember the example of Chuck Colson. In the story of his time with Bessie Shipp, we get a little picture of who Christ is, and who his people are to be. Like Christ, we can go into the places nobody dares to go and minister to the people everybody wants to forget. This is who we are, and this is what we are here for. By grace, we walk into prison cells. We minister to the dying and forgotten. Wherever we go, whether to Death Row or the corridors of power, we bring with us a message this world cannot conceive and a love this life cannot contain.