The new Rob Bell documentary just landed. It’s entitled “The Heretic,” and Bell laughs at the label when in the film he is introduced as such. It chills your blood, really.

I just reviewed “The Heretic” for the Center for Public Theology of Midwestern Seminary. Here’s a snippet from my review that I’ll expand upon below:

Doubt is the new “truth.” We hear emergent leader Peter Rollins say of Bell, for example, “he put his finger on a doubt and a questioning that was in that [evangelical] community, but wasn’t able to be expressed.” The sum and substance of The Heretic is that doubt is good, doubt is what makes faith comes alive, doubt frees you from the trap of red-faced literalistic evangelicalism. But doubt receives so much praise in the film, its little wings cannot bear it aloft any longer. Doubt is not truth; that makes no sense.

The Heretic does not hold back. It boldly urges us to “rethink” our conservative evangelical doctrine. The takeaway is plain: the truly virtuous spiritual person is not the one who follows the literalistic “fundamentalists,” but the one who doubts what the fundamentalists say, and rethinks what the fundamentalists teach. This is what Bell is after; this is what the film cheers, this kind of posture, as I’m at pains to say in my short review.

My point in writing this short piece is to engage this idea, which I sense is a popular one among the “spiritual but not religious” crowd. You could call them the “post-evangelicals.” Though the emergent church is not really a thing anymore, and though postmodern theology doesn’t seem to have a ton of academic oomph these days, the post-evangelicals are alive and well. As theologian Mike Kruger has shrewdly observed, they have made a veritable industry of telling their “de-conversion stories.” Figures like Bart Ehrman, Pete Enns, Rachel Held Evans, Jen Hatmaker, and Bell have made a splash through this project, which has turned out to be rather lucrative in some cases. Honestly, de-converting is big business these days; for example, though Bell critiques the “deep entrenchment” of evangelicals with capitalism, he charges $27.99 for his new book, and you can join him at his upcoming show’s pre-show event only after you part with $50.

De-converting ain’t easy.

What truly fascinates me about the post-evangelicals is this: they teach theology that is not only untrue, but self-defeating. Think about it: if your cardinal principle is to doubt everything, and if you call for an aggressive, no-holds-barred “rethinking” of all you hear, you cannot easily put the genie back in the bottle. In The Heretic, Bell does not surface awareness of this metaphysical imbroglio. He sharply critiques the “fundamentalists,” he tells audiences he has a “better way” to read the Bible, and he and his fellow on-camera gurus speak condescendingly of those who do not make space in religious communities for doubt and free thought, inclusion and openness. But this is ironic in the extreme, isn’t it? It seems you and I should doubt the fundamentalists, but not Bell. You and I should rethink conservative evangelicalism, but not post-evangelicalism. You and I should “include” all people, but not the megachurch types.

History bears out my skepticism about skepticism. If you doubt that doubt is a rough stone rolling, difficult to stop once loosed, take an evidence-driven theological spin through 19th-century American theology. Few people study it today, but the chronology goes something like this: the evangelicals of New England fought for Trinitarian doctrine; the Unitarians mounted a hostile takeover of New England Congregationalism, which was rather successful; then the Unitarians, once the new kids on the block with great new ideas, found themselves the old fogey of the fervent New England intellectual scene, as the Transcendentalists reenvisioned spirituality as an altogether different project, the tuning of the soul to the authentic self. On the story goes. The point, to restate it: you will struggle mightily to restrain doubt once it displaces truth as your cardinal principle.

Beyond the flashpoint of a given film, or the latest blog of a post-evangelical leader, we Bible-loving Christians must help the younger generation spot these lies. Even if our youth don’t go all the way and embrace post-evangelicalism, they’re still influenced by it, many of them. They think that doubting God and his Word opens them up to wonder, to beauty, to the mystery and pain and hope and agony of authentic living. They hear they should “rethink” everything, and so they start to loosen their grip on orthodoxy. Many of our youth don’t see, however, that they’re being led off into a much more closed-off way of thinking than anything they’ve heard before. The serious Christian, after all, takes their cues from the holy Word of God; the post-evangelical learns they must submit to the leadership of fallen men and women who have no writ from God, no summons from on high, no new prophecy to offer, no inerrant text to cite.

I have a better idea: let’s train our youth to trust the Bible, and to doubt their doubts. I first heard Tim Keller, in his brilliantly concise manner, say this phrase. Doubt your doubts. You could write a 700-page tome on epistemology and not do much better than those three words. It’s not that the Christian turns off their brain in coming to faith, after all. In fact, conversion requires and activates the full horsepower of the human mind, and the human heart, and the human soul (Matt. 22:34-39). But we learn through Christic conversion to distrust the world’s wisdom, to resist the serpent’s lies, and to nurture a healthy skepticism about all Messiahs who do not descend from heaven itself, who make no atonement for sin, who do not rise out of the grave to sit at the Father’s right hand, and who will not judge the quick and the dead.

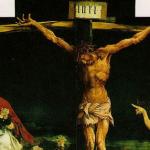

And we should see and say this as well: the gateway to beauty, wonder, mystery, authentic humanity, and a full-sensory comprehension of the raw pain, ugliness, madness, and hope of this world runs through the Bible, not around it. Biblical doctrine bursts with meaning; biblical truth no one can master. Who can wrap their arms around the God of Scripture, and bring him down to size? Who can capture the poetic aestheticism of creation ex nihilo, and do justice to it? Who can search out all the depths, and the heights, of salvation extra nos, God reaching into the very world of men to redeem them through death, even death on a cross? Here’s the answer to all these questions: no one.

The Christian faith is the gateway to true pleasure, true meaning, true wonder (Psalm 16:11). What does the Psalmist say of the living “knowledge” of God? Such knowledge is too wonderful for me; it is high; I cannot attain it (Psalm 139:6). So it is with us. We love God’s “wonderful” knowledge. We doubt our doubts. We train the church to spot lies. We help the rising generation in particular see that the “post-evangelicals” do not actually break with rigid doctrine. They do not truly make space for free-thinking. They set themselves up as new prophets, bearing inerrant words, ranking as new apostles over the old ones, but they are no such thing. They are, like all of us, deeply fallen; they are, like all of us, in desperate need of the grace of humiliation, and the grace of salvation, and of rethinking their rethinking.