Appalachian folk magic came about because it gave these people a sense that things were going to be alright even in the poor circumstances most found themselves in. It let them get a handle on things, one way or another. And it works. While you won’t get rich quick, you can use it to better the circumstances the world sets against you, even if you’re still piss-poor afterward. With it, you can foresee the cards you’re about to be dealt and change the tables somewhat in your favor.

Appalachian conjure was kept secret mostly from those with a suspicion and mistrust for it—usually the well-off church folk who sat on their own pedestal every Sunday morning. Anything “primitive” or deemed “against the good book” was of the Devil himself. Mamaw scrunched her nose at those people. You can go to every church in Unicoi, Carter, and Washington counties, but that ain’t making you right with the Lord. When the well-off folks are in trouble, they’ll need someone and won’t be able to get the “special” help they need.

American folk magic is a melting pot of practices stemming from Irish, Scottish, German, Italian, and other European sources as well as African and Native American sources. For example, the uses of different waters like rainwater and ocean water originates mostly from the British Isles. The use of dirts and dusts comes from the Native Americans and the African slaves brought to this land. The act of placing bowls and pans under the bed for works or spells comes from Jewish folklore; the practice of throwing spells and remnants behind oneself into a stream comes from European traditions; and the use of grave dirt comes from African and European traditions.

It can be difficult to discern where methods and practices originally came from, especially with generations of change and adaptation. Some things are added or taken away based on location, timing, and need. That’s why you will always find a handful of spell recipes for the same purpose but with varying ingredients or tools. For example, hotfoot powder, which is used to make folks leave you alone or even leave town, sometimes consists of hot peppers, spices, and sulfur. But those things aren’t found often here in the mountains, so most people mix black pepper and salt instead, as they are cheap and readily available. I’ve also heard of adding spiders, bugs, and other things to scare or chase folks away. We don’t call it “hotfoot” in the mountains, either: to us it’s “uprooting” people to make them leave and never return.

Although some prefer to stick to tradition, these roots grow and change. We can honor and trust in the strength and support they gave through the racism, genocide, and persecution our old folks suffered. Through all the troubles, they preserved the knowledge and practices that helped make everything bearable and gave our ancestors an upper hand against the trials that held them.

These hills have been soaked in blood, covered with bones, and have resounded with cries of war and birth over and over. They’ve witnessed life and death occur more times than our minds can comprehend. Their soil has been stained by the blood of soldiers and slaves alike. These same struggles have given rise to our culture today in the form of tradition, folk songs and art, and good cooking.

Our weather and seasons and landscape shaped the way we farm and plant, the foods we hunt and grow, and the remedies we created for ourselves when the mountains locked us in. But it wasn’t just with us that the mountains did this. They’ve been shaping the culture, practices, and magic of people as long as they’ve been inhabited, even long before the Cherokee put down roots here. Very likely, the land of your folks did the same to your family and community.

History here is weaved into the spider’s web. The river runs warm with the paranormal, and witchcraft whispers on foggy autumn mornings just before the church bells start ringing. Let’s now turn to the superstitions and tales of these hills: those bedtime stories that may have root in dream or history, echoes of haints in the graveyard, and chills when an unseen guest is knocking at the door.

Superstition is the fuel behind folk magic. Of course, we don’t think it to be primitive or backward; it’s what the old folks always did and said, so we do the same because they got along alright with it. Personally, I can validate that most of these tales are true. Superstition finds its spot nestled around the needs of humanity, whether it be food, weather, hunting, childbearing, or labor. It guides us from accidentally bringing ill onto ourselves and offers protection from the same from others. It is there, in the pit of those needs, that mountain witchcraft and healing is born, cultivated, and preserved across generations.

___________

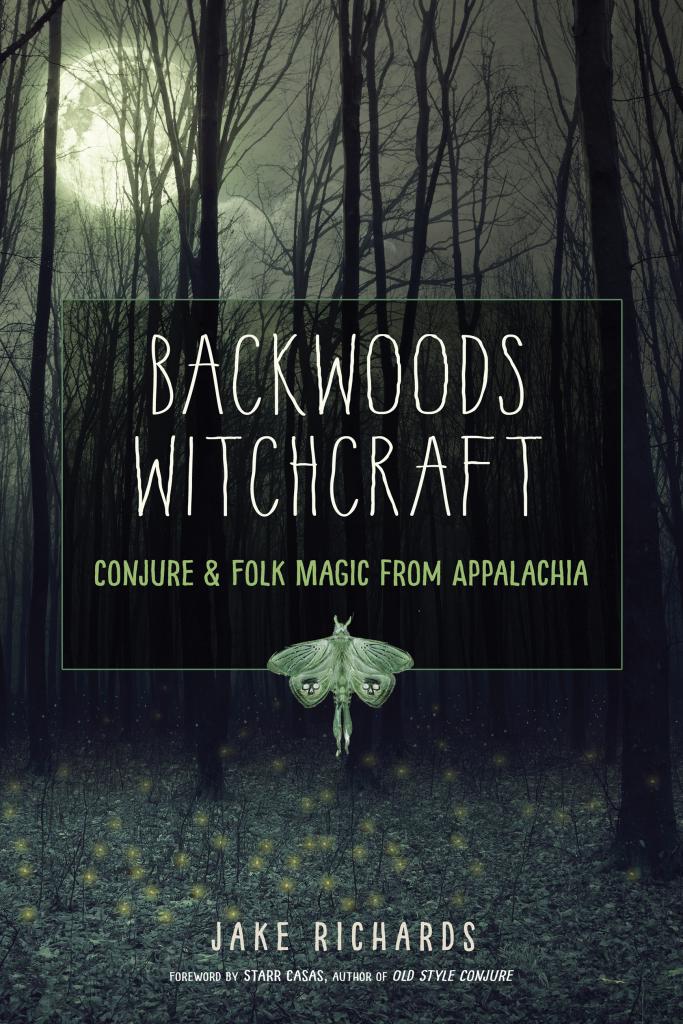

Adapted, and reprinted with permission from Weiser Books, an imprint of Red Wheel/Weiser, Backwoods Witchcraft by Jake Richards is available wherever books and ebooks are sold or directly from the publisher at www.redwheelweiser.com or 800-423-7087.