This week, Scot Miller is blogging about Robert Gagnon’s book, The Bible and Homosexual Practice: Texts and Hermeneutics, which many readers of this blog are sure will convince Scot and me that we’re wrong about the gays. -TJ

In my first post about reading Gagnon, I wanted to be clear about the prejudices I brought to my reading. The first prejudice was that fidelity to the biblical message is important to me. Here are two more of my prejudices:

Second: I am aware that the Bible can be misread in dangerous ways. The denomination in which I was saved and educated and ordained — the Southern Baptist Convention (or whatever it wants to call itself now) — was founded in 1845 because Baptist slave-holders in the South wanted both to be foreign missionaries and to keep their slaves. While Baptists in the North objected to appointing slave-holding missionaries, the Southern Baptists defended the practice of slavery by appealing to the Bible.

In a recent editorial, my former Church History professor Bill J. Leonard, gives an example of Southern Baptist rhetoric about slavery:

In an 1822 address to the South Carolina legislature, Baptist pastor Richard Furman insisted: “Had the holding of slaves been a moral evil, it cannot be supposed, that the inspired Apostles, who feared no the faces of men, … would have tolerated it for a moment, in the Christian Church….” The biblical writers, Furman said, let the master/slave relationship “remain untouched, as being lawful and right.”

He concluded: “In proving this subject justifiable by Scriptural authority, its morality is also proved; for the Divine Law never sanctions immoral actions.” “Biblical defenses” of slavery flourished throughout the antebellum South.

Southern Baptists could defend the practice of slavery by appealing directly to the plain sense of scriptures like Ephesians 6:5-6: “Slaves, obey your earthly masters with fear and trembling, in singleness of heart, as you obey Christ; not only while being watched, and in order to please them, but as slaves of Christ, doing the will of God from the heart.”

Southern Baptists could defend the practice of slavery by asking the abolitionists, “Where is the scriptural condemnation of slavery? Where does the Bible advocate the abolition of slavery?” Southern Baptists knew that there is no such scripture, and they could accuse the abolitionists of being unfaithful and disobedient to God’s plan as revealed in the Bible. The slave-holders, not the abolitionists, were those truly faithful to the Bible.

Southern Baptists were wrong.

The fact that Southern Baptists could confidently recognize that the Bible tolerates the practice of slavery and could make a logially consistent and coherent biblical argument for Christian slave-ownership does not mean their interpretation was correct.

So while I want to be faithful to the message of the Bible, I’m suspicious of the overconfidence some people have in identifying their own interpretations of scripture with the biblical message, just as I’m suspicious of people who have an absolutely clear moral vision.

My personal rule: anyone with biblical overconfidence and absolute moral clarity is probably overlooking something important.

To be clear, abolitionists like Daniel Goodwin and Frederick Douglass made a biblical case for the abolition of slavery, but their case was not made by appealing to specific passages that rejected slavery. Instead, the Christian abolitionists had to appeal to “the spirit and tendency of [the Bible’s] teaching,” which they could summarize in Jesus’ commandment to “love thy neighbor as thyself” (see Jennifer Wright Knust, Unprotected Texts, p. 13).

Third: I am better trained as a philosopher than I am a biblical scholar. Although I majored in Bible as an undergraduate and graduated from seminary with classes in Greek and Hebrew exegesis, my doctoral work was in philosophy of religion.

I taught philosophy to undergraduates for 12 years, and the most frequently courses I taught were critical thinking and applied ethics. This means that I’m well aware of what makes for good and bad arguments, and I’m fairly well versed in moral theory and what it means to think ethically.

So my reading of Gagnon pays more attention to how Gagnon develops his argument than to his biblical scholarship. I’ll also be listening more closely to any moral arguments and justifications he uses as he discusses homosexuality and homosexual practice.

I also believe that my training in philosophy will help me be fair to Gagnon’s argument. When Tony originally announced that I would be blogging my review of Gagnon’s book, some people expressed their skepticism that I could be fair, especially since on Tony’s blog I have engaged in rather lengthy defenses of same-sex marriage and lengthier rejections of the “sin” of homosexuality.

(Frankly, I was surprised that no one was glad or even hopful that I was finally going to be exposed to overwhelming evidence from Gagnon which would devastate my support of the LGBTQ community and convert me to the biblical truth.)

But as I used to explain to my students, philosophers are trained to evaluate arguments and not the particular conclusions that people reach. Whether I happen to agree or disagree with someone’s conclusion is really irrelevant to the strength or weakness of the argument.

I can have high praise for someone who has a strong argument for a conclusion with which I disagree, and I can reject arguments which do a bad job at supporting my conclusion.

So these are three of my prejudices I bring to my reading of Gagnon. I have other prejudices, to be sure, but these three seem most important.

I suppose I should add that I am a happily married heterosexual, so I’m not as personally invested in the issue of homosexuality as others are.

I’m also not a church leader or political figure or opinion-maker or academic, so I don’t have an ax to grind or any obvious material interests to gain from taking a particular position.

I did perform a wedding ceremony for my niece and her same-sex partner, both of whom I love and respect with my whole heart.

Which reminds me that I hope I am prejudiced to value human beings over moral or theological principles.

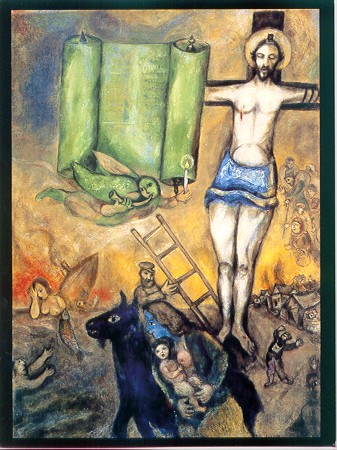

When Jesus was caught breaking the Law by gathering grain on the sabbath, Jesus said to his accusers, “The sabbath was made for humankind, not humankind for the sabbath” (Mark 2:27).

In a similar way, I suspect that the Bible and moral principles are made for human beings, and not the other way around.