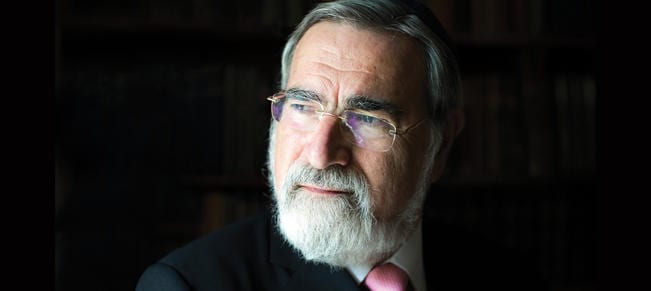

On Saturday 7th November the former chief rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth, Lord Rabbi Sacks, lost his battle with cancer at the age of 72. This conversation is an excerpt from a longer interview in which Sacks eloquently summed up the problem with political battles that have become ever more divisive in the four years since this Q&A was recorded.

Rabbi Sacks was made a life peer and given a seat in British Parliament’s House of Lords in 2009 and spent 22 years as the Orthodox chief rabbi between 1991 and 2013. During that time, he was credited with revitalising the Jewish community in Britain and was a key figure in re-establishing the richness of Jewish thought, ethics and spiritual identity in the public sphere.

Prince Charles was among those to pay tribute to Rabbi Sacks:

“His immense learning spanned the sacred and the secular, and his prophetic voice spoke to our greatest challenges with unfailing insight and boundless compassion. His wise counsel was sought and appreciated by those of all faiths and none, and he will be missed more than words can say.”

The British prime minister, Boris Johnson, said he was “deeply saddened” by Lord Sacks’ death, adding: “His leadership had a profound impact on our whole country and across the world.”

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, commented that Rabbi Sacks “devoted so much of his life to reflecting on God at the most profound level – and we are all the beneficiaries of his wisdom”. He also said:

“Rabbi Sacks was always someone you could relate to instantly…He had a deep commitment to interpersonal relationships – and when you met him you couldn’t help but be swept up in his delight at living, his sense of humour, his kindness and his desire to know, understand and value others.”

In 2016 Lord Sacks was awarded the Templeton Prize, which honours an individual who has made an exceptional contribution to affirming life’s spiritual dimension. Host of Unbelievable? Justin Brierley, spoke with Rabbi Sacks shortly after he received the prize and much of what the former chief rabbi said is still relevant four years on – particularly his comments about politics and morality. You can listen to the whole interview here.

Justin Brierley: You had a successful undergraduate and graduate career at Cambridge University. One of the things you recognised was that not everyone retained religious observance among the Jewish community while you were there. What made you hang on to your faith and what, do you think, made your peers disengage with it?

Rabbi Sacks: My father came to England as a refugee from Poland. My parents were never really able to have an education or live their dreams. I felt very privileged and responsible – I’m the eldest of four boys – that somehow or other we were going to be given chances our parents never had.

My parents felt that being Jewish was something special. Whereas I think some of my contemporaries came from families that were better established. And for them, Judaism was something they just took for granted, so they could perhaps lose it without feeling they were losing part of themselves.

When I became chief rabbi, I had to remind people that being Jewish in the past was no guarantee that our children would stay Jewish in the future. I asked: “How long does inherited wealth last?” And they said: “About three generations.” Many of our children are the children of the fourth generation, so we’re going to have to help them make it themselves. We built a lot of Jewish schools because we couldn’t rely on tradition anymore, we had to rely on people knowing what it meant to be a Jew. And because they know, they care.

While studying philosophy at Cambridge I visited America, because there were a lot of American rabbis who were academically very Impressive. This name kept coming up again and again, Rabbi Schneerson, who was somebody other rabbis held in awe, because he’d taken this very small, Russian, mystical sect and transferred it to America in the Holocaust years and turned it into this outreach movement, this evangelising move – not to non-Jews, but within the Jewish people. Nobody had ever done that before.

I tried to understand why he was the first Jew who really went out to other Jews who were lost and approached them in love and I suddenly realised that he had lived through the Holocaust. He’d seen Hitler hunt down every Jew in hate. Jews believe in something called Tikkun – mending the world. How do you mend an evil that great? I suddenly realised the only way you can mend that is to search out every Jew in love. And that was what he was trying to do. A post-Holocaust Tikkun, a kind of mending of this enormous wound in the human spirit.

Leading is the last thing in the world I ever dreamt of doing, least of all in some religious capacity. And here Rabbi Schneerson was challenging me. Somebody that famous, that great and that holy – if you like – saying something like that to you keeps you awake at night! It didn’t instantly change my life, but it stayed with me for five or six years, until it changed my life.

JB: Donald Trump has just received the presidential nomination. What’s your view of him?

RS: I never say anything about particular politicians and I don’t believe religious leaders should ever get involved in party politics. So, I’m not going to answer you directly. But I do think that American political culture has had this extraordinary tradition of speaking to what Abraham Lincoln called “the better angels of our nature”. In his second inaugural address, he said:

“With malice toward none and charity for all…let us strive on to finish the work we are in to bind up the nation’s wounds.”

There was something profoundly healing about Abraham Lincoln’s language. And although he wasn’t a regular churchgoer, he proclaimed a national fast for America in the middle of the Civil War in 1863. Because he said if we are tearing each other apart, there must be some collective sin that we are guilty of.

Abraham Lincoln was not somebody who demonised his opponents. The extraordinary book about him, Team of Rivals, explains how he actually made the people who deposed him as president part of his closest team. Abraham Lincoln knew what it was to use the language of politics as a mode of healing.

When feelings are very raw – and they are now almost everywhere in the world, because the pace of change technologically, economically, politically has got so rapid – we need politics as a form of healing. I wrote a book about this many years ago called The Politics of Hope. I called it that because the thing I most worry about is the politics of hopelessness and fear. That generates blame, a sense of victimhood – it wasn’t us it was them. And that generates the world’s worst politics, that generates the politics of hate.

JB: Why do we seem to have forgotten that in the West?

RS: Somehow, in the immortal words of Princess Elsa in Frozen (I hope you get my rabbinic reference here!) the West has “let it go”. It has externalised what it wants internalised, it has outsourced responsibility and reduced ethics to economics and politics, which means we are dependent on the market and the state forces we can do little to control.

We have this magical belief in the power of the market to deal with everything. If it is a matter of choices, that’s the market, if it’s a matter of the consequences of choices – you made a bad choice, you smoke too much, you’re overweight – the state will deal with it. So, we outsource morality to the market and the state.

I love the market and I love the liberal democratic state, but they can’t solve all our problems, there has to be this third thing called conscience. And conscience always comes – although it’s very individual – from being part of a moral community. You can’t outsource moral responsibility, but that’s, I think, what we tried to do because it was so seductive. If you want it and can afford it and can get it somewhere on the internet, why not, you know, just abolish morality?

Our children and grandchildren are part of this internet, social media generation where they’re being bombarded, saturated with images, all of which suggests that you can have it all now. And, of course, that is the death knell to any civilization. Because, as Sigmund Freud said:

“Civilization is built on the capacity to defer the gratification of instinct.”

I really think this is deeply serious. It doesn’t hit front-page news, but it’s there underneath. Civilisations begin to fail when they lose the moral voice and the moral inspiration that created them in the first place.

JB: When you received the Templeton award, you thanked the God who “believes in us so much more than we believe in him”. What did you mean by that?

RS: I mean that he had the faith to create a universe out of which would emerge life and then us. If you read the opening chapters of the Bible, Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, and the generation of the flood, there’s the extraordinary line that “God regretted that he had ever created man and it grieved him to his very heart” (Genesis 6:6). So it begins with divine disappointment.

After the flood, he begins again with Noah and kind of pledges himself: “Maybe I’m going to be disappointed but I’m going to stay with it.” Therefore, it always seemed to me that our faith in him was pretty secondary in the scheme of things. His faith in us is absolutely essential.

That, of course, is really at the heart of Abrahamic monotheism. I always say that the Greeks gave us tragedy and the Hebrew Bible gave us hope. Judaism is the principle defeat of tragedy in the name of hope. That hope is grounded in the fact that our merely being here is testimony to God’s faith in us.

Listen to Rabbi Sacks being interviewed by Justin Brierley

Subscribe to the Unbelievable? podcast