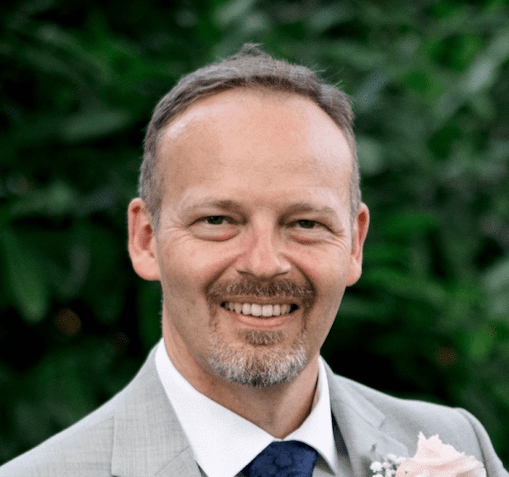

Jim Thring became a Christian as a young adult. He subsequently lost his faith and spent nearly ten years as a committed atheist. He has since come back to faith through an intellectual and personal journey. We asked Jim to share some of his story on our Christmas special. You can also hear more from Jim next week in part two of this interview, where he speaks about the impact his deconversion had on relationships, particularly his marriage (his wife remained a Christian).

How did you come to faith?

I was brought up in a very loving household in East London and knew very little about religion and the Christian faith. So, I was quite ambivalent towards religion and faith in general. I was neither here nor there, to be honest. I wouldn’t have called myself an atheist either.

I became a Christian at University at 19, almost accidentally, you could say! I met some Christians and one of them kept talking about this place called Menzieshill. It was a sunny afternoon and she said: “Would you like to come? We’re all off there.” And I said: “Great”, because it was a really nice day to go for a walk.

I found myself sitting in the back of her car with my friend Ian and I asked him what this hill was like. He looked at me incredulously and said: “Menzieshill is the name of a church.” So, I accidentally found myself in this situation! And I thought: ‘How on earth have I allowed myself to go to church? This is ridiculous! However, it might be quite interesting to go.’

And I did. And I started to ask questions about life’s purpose. It was like being a child again, I had a chance to do life a second time around – a second chance. When I lost my faith, people questioned whether I really was a Christian in the first place. But the answer is yes, I absolutely was a Christian. This wasn’t a nominal Christianity. It wasn’t something I inherited from my parents. It was a decision that I made. And at that time, I assumed I would live that for the rest of my life.

What was the trigger that started you on a journey of deconstruction?

Well, it didn’t happen overnight. You don’t suddenly wake up one morning and say: “I’ve now changed my mind.” There were a number of things that happened over the course of a few years. My faith became more about what I knew and how much I knew rather than who I knew.

University was great. The Christian Union was very strong. And I carried on with my faith for a number of years, but I think I was faced, like many people, with the ups and downs of real life. And I started to compartmentalise my life. I was very much a Christian and doing the Christian thing when I was with other Christians, but I grappled with something that I guess all Christians grapple with, which is exclusivity. You know, you’re working alongside people who aren’t Christians, they seem like very nice, good people who are doing things with the best intentions.

If God stops meaning something to you in your day-to-day life, the next logical question is: then why carry on believing?

Over time there was a kind of struggle with this dual life. It felt like I was leading a different life as a Christian to what I was leading outside of the Christian faith. I think the other thing was the simplicity of the gospel that I received when I first became a Christian and the uniqueness of Christ just started to get lost. And my faith started to become a bit more pedestrian and stagnate somewhat.

So, when you add these layers together – a faith that becomes a bit monotonous, the intellectual struggles and a faith that’s less about a relationship – it becomes a recipe for the potential to deconstruct. And I think when those intellectual questions come in to that, that’s the real catalyst and you’re then at this kind of critical point.

The way I summarised it in my mind a few years ago was that if God stops meaning something to you in your day-to-day life, the next logical question is: then why carry on believing? And that was what happened.

You then spent nearly a decade as a non-Christian. What did that look like?

When I left my faith, I kind of went the whole hog. I was quite hard-line, to be honest, and very defensive towards Christians. I took this view that I know the inner workings of evangelical Christianity, so you can’t pull the wool over my eyes. You can’t fool me with your ‘bring and buy sale’ or your Sunday lunch, I know you’re probably trying to pull me back through the church door that I’ve just walked through!

I liked to consider myself an honest atheist. I didn’t just backslide slightly and take the position that there was still objective morality. I thought: ‘If you’re an atheist, then you ought to be a materialist atheist.’ I discovered the ‘new atheists’ around that time (although I didn’t leave my faith because of them). I went to a debate between Professor Richard Dawkins and Professor Robert Winston and got a signed copy of a Richard Dawkins’ book. I thought: ‘This is it. I’ve seen the light now. And I’ve put to bed all those fanciful ideas of faith.’

There’s a British comedian called Jimmy Carr and in one of his sketches he said that as a child he believed in an invisible friend who granted all his wishes, but then he stopped going to church! I laughed at that, very knowingly, thinking that’s where I am as well. Of course, looking back I realise if that was your picture of God, no wonder you would leave church, but the Christian God is so different to that.

What led you to reconsider your secular humanism?

Again, it didn’t happen overnight. I think I softened from that hard-line, atheist humanist view. In the early years of being an atheist, I really did ride the rhetoric of people like Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins. And I think I used that to keep justifying to myself intellectually that I’d made a very sound decision. I’ve chosen to do life my way and these very intellectual people can back that up in some way.

But then I found myself starting to question the narrative I was listening to online or on social media. Some of the content got a bit pokey and tended to put Christians down as people who weren’t thinkers, who weren’t rational at all. And it almost felt like “if the Church says this, then we’re against it” or “if Christians believe that, then we’re against it”. I remembered Christians I knew from years ago who are a lot smarter than me who still stood by their faith. And I started to feel a bit softer and think perhaps it’s not quite as straightforward.

I realised that my atheism had as much of a powerful belief behind it

That led me to a period where I realised that reason, logic and rational thinking are not tools that are only available to the atheist. And they’re not things that mean you’re obliged to follow the path that will ultimately lead to atheism either. I think as a very strong atheist I thought you could dismiss anything. British illusionist (and former Christian) Darren Brown did a programme called Messiah, where he talked about the power of belief to drive you down a particular track. And I used to think: ‘Yeah, that’s what I went through and now I’m free from that.’

But I realised that my atheism had as much of a powerful belief behind it. The maxim that there is a materialist explanation for everything is also a very powerful belief. Because what it means is it doesn’t matter what evidence someone puts in front of you, it doesn’t matter what arguments, however well-constructed they might be or how valid they are, you’ve got a reason to dismiss them. And I think I started to try and be honest about where my atheism lay, what supported that and kind of reconsidered it again.

A number of different things also happened on a personal level. I met with Christians a bit more, through my wife (who was still a Christian). No one was too pushy with me, but it was just nice to meet with people. And I think that softening laid the groundwork really, for me to think: ‘Maybe I could look at some of these arguments for Christianity and see if there is a defence.’ So, I surreptitiously, without my wife knowing, used my Kindle to look up somebody who could help me through some of the questions.

Probably the biggest thing for me was origins and evolution. And I came across John Lennox’s book Gunning For God: Why the New Atheists are Missing the Target. He started to address some of those things that I thought were really knock down arguments against the Christian faith. And I think what he did was turn it around and suggested that you can apply these arguments to atheism as well. A number of other things were happening alongside that, and that was the beginning of that journey.

Do you feel like your faith now is different to your original faith? Or is it similar, but with a stronger foundation?

It’s the same faith I had when I first came to Christ. It’s almost like that first love you discover when you first encounter God, but it is different. Having come through this experience, I feel like I’ve been able to reflect on why I deconstructed or deconverted. And I think that my faith now feels stronger for the fact that I can see that there are personal reasons why I’m a Christian. I thought that my reason for being an atheist was purely intellectual. But it took time for me to realise that actually, there were personal reasons why I was an atheist.

My faith is as strong if not stronger than it was before. I feel that it’s defensible. And I have discovered Christian apologetics. I think Christian apologetics is very good at helping people to unblock those artificial barriers to faith. But I think it’s also really good at helping Christians to be encouraged in their faith.

You’re never going to know the answer to every question, you’re never going to amass all knowledge, it’s just not possible. But there’s enough there that you can take a step back and see the big picture. It’s a little bit like those magic eye pictures that if you stare at this pattern for long enough, but you don’t look too much at all the details, you just look at the whole thing and you relax a little, eventually you see the image. And that’s what it’s like for me at the moment.

Next week, you can hear more from Jim sharing the impact his deconversion had on relationships, particularly his marriage (his wife remained a Christian).

Listen to more of Jim’s story here

Subscribe to the Unbelievable? podcast