We Christians need to be on guard in our understanding of such movements as contemporary Paganism. We tend to lump all of modern Paganism into one general and distorted category. We often fail to account for the vast complexity within the movement and articulate Paganism accurately. For all our concern about pagan idolatry, we may be guilty at times of making their idols for them. We need to develop the practice of respect for understanding their practices, rituals, and beliefs.

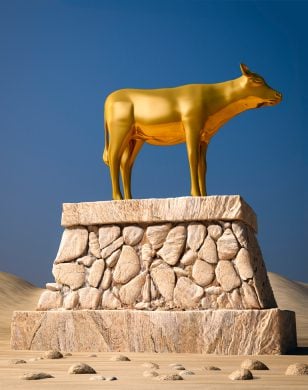

The Apostle Paul was a very nuanced Christian thinker. He understood the world of ancient Paganism and respected the Romans and Greco-Roman culture enough to understand carefully what they practiced and believed. As Paganism lost ground in the ancient world with the rise of Christianity, a sophisticated understanding of pre-Christian or pagan religions also lost ground. Unlike many Christians throughout the ages, Paul understood that idols were not to be identified at every turn with pagan deities. In Acts 17:16-34, we see that he (like many ancient Pagans) understands that the statue to the unknown God is not a god, but that it represents or can represent God beyond the idol. The same goes for Paul’s reflection on idolatry in 1 Corinthians 10. The idols to which food was sacrificed were nothing, even though in his estimation, the idols were associated with demons (1 Corinthians 10:14-22). In other words, Paul was able to distinguish the material object from what he understood to be a demonic presence.

Just as Paul had a more complex understanding of Paganism’s practices and beliefs, including the worship of idols in his day, we need the same kind of complex awareness of Paganism and its understanding of the sacred in our day. It would be too simplistic to say that Pagans today worship nature. Contemporary Paganism doesn’t generally see a tree as a god, but as an extension of the divine pantheistically or panentheistically conceived (but pantheists and panentheists are not all Pagans). The natural world is sacred and an extension of the divine, but nature is not generally worshipped today as a divinity.

If one were to account for a theology of contemporary Paganism, one would have to place hard polytheism involving distinct deities on one end of the spectrum and a completely metaphorical account of divinity on the other end: here divinity would be viewed as a metaphor for nature or humanity or society (some Pagans view the gods atheistically as symbols without ontological reality). In between, there is a variety of understandings, including a combination of the two ends of the spectrum. Across the spectrum, nature plays a key role. The emphasis is not on right belief, even though beliefs do have a bearing on practice; for example, whatever beliefs one branch of Paganism entails involves a connection to nature and care for it. The emphasis on sacred regard for nature is widespread.

Gender is also key to Paganism. The divine can be seen with a female face and body. This is very different from most Christian understandings of God, though it connects contemporary Paganism with ancient forms of Paganism. There are female and male forms of deity, whether viewed literally or metaphorically. The divine can be female in origin. While many educated Christians do not gender God, still, Christianity has often had a very patriarchal view of God, even though Scripture uses feminine and motherly associations at times to speak of the Creator. For Paganism, the female gender is associated with birthing (not creating) and nurturing nature.

Contemporary Pagan religions are largely praxis-based faiths and spiritualities. Harmony with nature is a key value. The more we are out of harmony the worse it gets. Many Evangelicals care for the creation (creation care) since they believe that we should be good stewards of the earth until everything ends because God is its creator. In contrast, the underlying motivation in caring for the earth for Pagans is that the earth itself is sacred. For contemporary Pagans, the earth is not a creation given to us; so, we don’t have dominion over it since we are bound up with it. As the contemporary discussion on the environment developed, it shaped Paganism as a nature religion in a significant way. Honoring and having a significant regard for nature is key to Paganism in the contemporary context.

It is very difficult for modern Paganism with its praxis-oriented spirituality to take seriously Christianity’s worship of a Creator God, when many Christians jettison care for what we call creation. The loss of practical consideration of creation stewardship on the part of Christians has perhaps created a vacuum that has been filled by the sacralization of nature by Paganism today.

Why would many Christians have no regret at destroying an ancient forest by paving roads that will bear fleets of SUVs when we would never allow SUVs to pass through our sanctuaries and run over our communion tables? How can our churches with their symbols be viewed as sacred when they are built by human hands, and not the creation at large, when it is built by the hand of God?

While we Christians would not wish to divinize the creation, we should also guard against turning our own creations into idolatrous machines that wreak havoc on what God himself as made. When we do, we are guilty of worshiping our own creations rather than God. At least, Pagans old and new are charged with worshiping God’s creation (Romans 1:18-25), not our own.

This piece is cross-posted at The Institute for the Theology of Culture: New Wine, New Wineskins and The Christian Post.