I remember someone claiming there is too much talk of justice in Evangelical circles these days. From what I recall, this person felt that highlighting consideration of justice was distracting people from placing due emphasis on the gospel. This individual viewed justice as an appendix to the gospel at best, or possibly even extraneous to it.

I remember someone claiming there is too much talk of justice in Evangelical circles these days. From what I recall, this person felt that highlighting consideration of justice was distracting people from placing due emphasis on the gospel. This individual viewed justice as an appendix to the gospel at best, or possibly even extraneous to it.

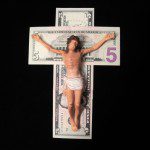

Certainly, Evangelicals must focus consideration on the proclamation of the gospel or good news of God’s grace revealed in Jesus Christ; even so, the Bible sets forth that the proclamation of the gospel of the kingdom involves words and deeds. God’s Word is not static, but active, dynamic and life-changing, transforming all of life through the miraculous presence of God’s living Word Jesus in our midst through the Spirit. His presence in Word and deed calls for a response of repentance and faith in view of his kingdom reign and shalom (See for example Matthew 4:23-25; Matthew 9:35-38; Luke 4:16-21; Luke 7:18-23; John 1:1-3, 14, 20:30-31). Moreover, the gospel is all about justice: God is just and loves justice (Psalm 146:5-9; Isaiah 58; Amos 5:21-24; 2 Thessalonians 1:6); God justifies the ungodly (Romans 5:1-11), and God makes his people just (James 1:26-27). See my engagement of the gospel and justice at “What Is Biblical Justice?” and “What’s the Big Deal about Justice?” as well as chapters fifteen and sixteen of Exploring Ecclesiology: an Evangelical and Ecumenical Introduction (Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2009; the volume was co-authored with Brad Harper).

Having said all this, it is not simply certain Evangelical Christians who raise concerns about justice. Some Buddhists do, too. A leading Buddhist scholar, Walpola Rahula, claims the following:

The theory of karma should not be confused with so-called ‘moral justice’ or ‘reward and punishment’. The idea of moral justice, or reward and punishment, arises out of the conception of a supreme being, a God, who sits in judgment, who is a law-giver and who decides what is right and wrong. The term ‘justice’ is ambiguous and dangerous, and in its name more harm than good is done to humanity. The theory of karma is the theory of cause and effect, of action and reaction; it is a natural law, which has nothing to do with the idea of justice or reward and punishment. Every volitional action produces its effects or results. If a good action produces good effects and a bad action bad effects, it is not justice, or reward, or punishment meted out by anybody or any power sitting in judgment on your action, but this is in virtue of its own nature, its own law. This is not difficult to understand. But what is difficult is that, according to the karma theory, the effects of a volitional action may continue to manifest themselves even in a life after death… (See Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught, with a foreword by Paul Demiéville, 2nd edition, New York: Grove Press, 1974, page 32).

To my understanding, Dr. Rahula claims that ambiguity results from belief in a supreme being sitting in judgment. Some theists have also raised concern over God operating in an arbitrary manner, and have proposed that God is subject to the moral laws of the universe. While I share the concern over the idea that a law could be arbitrarily imposed, I maintain that God does not operate in an arbitrary manner. The moral laws of the universe flow from his character, which we seen on display in the life and work of Jesus Christ as disclosed in the Bible. I do not find anything arbitrary about Jesus’ life witness. He is constant in all his ways, as the ultimate revelation of God as the True, the Good, and the Beautiful.

Certainly, good actions produce good effects and bad actions bad effects, as Dr. Rahula maintains. Is it a law of nature? It is hard to say. When we consider nature, if we mean the natural world, we see not simply order but chaos and randomness, perhaps even arbitrariness at times.

Having said that, good actions are consonant with the character of God as are good effects. Judgments as good or bad are not arbitrary; they are relationally grounded in that God engages people truthfully and graciously. Now can karma ultimately make space for grace (undeserved favor), or does the karmic system exclude or jettison it? We cannot consider justice apart from truth and grace, if we are thinking of biblical justice. After all, biblical justice is revealed ultimately in the person and work of Jesus Christ as God’s supreme revelation: he is even greater than the great law of Moses that speaks of the revelation of God’s character involving steadfast love and truth (See Exodus 34:6): “For from his fullness we have all received, grace upon grace. For the law was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ” (John1:16-17; ESV).

Against the backdrop of Evangelical and Buddhist concerns about justice, Jesus is the perfect integration of grace and truth in the flesh (1:14; 18).[1] He is the embodiment of moral justice; divine judgment occurs in and through him. What is wrong with justice? Everything is wrong with ‘justice’ apart from Jesus and nothing when framed in view of him.

____________

[1]In keeping with the New Testament English translation, “‘Full of grace and truth’ echoes the Hebrew word pair ‘steadfast love’ and ‘truth’ (… hesed… and emet; e.g.; refer to Ex. 34:6) that speaks of God’s covenantal love and faithfulness.” Gail R. O’Day, “The Gospel of John: Introduction, Commentary and Reflections,” in Luke-John, The New Interpreter’s Bible 9, ed. Leander E. Keck (Nashville: Abingdon, 1995), pp. 522-23. In Exodus 34, we find that God reveals his glory to Moses in the giving of the new tablets of stone. Here God tells Moses that he is compassionate and gracious, and that he is slow to anger and abounding in love and faithfulness. God maintains love to multitudes and forgives their wickedness, rebellion, and sin, while not allowing the guilty to go unpunished (Ex 34:1-7). Although the Law of Moses is glorious, gracious and truthful, Jesus as the Word incarnate reveals the fullness of God’s glorious goodness, steadfast love, and truth. A. T. Hanson also sees this expression “full of grace and truth” hearkening back to Ex 33–34. See Hanson, Grace and Truth: A Study in the Doctrine of the Incarnation (London: SPCK, 1975), p. 5. See Paul Louis Metzger, The Gospel of John: When Love Comes to Town (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2010), pp. 279, 283.