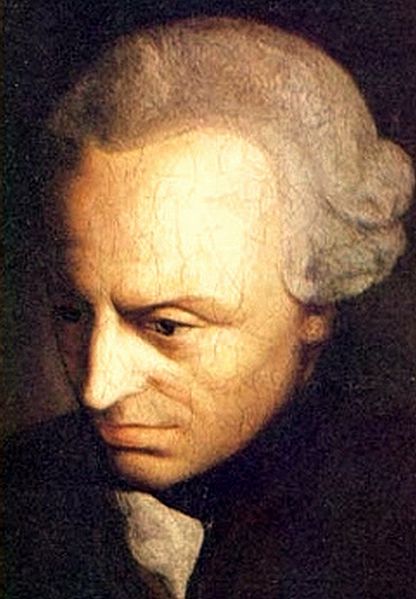

The history of faith and science is a tumultuous struggle on most accounts. Immanuel Kant’s philosophy reflects key elements of the struggle. In his Critique of Pure Reason, he writes of having limited or denied knowledge to make room for faith. For those who follow Kant’s lead, one could no longer make claims of factual knowledge of God. Knowledge of the factual kind was limited to the realm of physics. Kant thereby filled the metaphysical gap reserved for deity in previous ages.

As already noted, though, Kant did not remove God from consideration. God performed a helpful role in terms of ethics. Such ideas as God, the immortality of the soul, and eternal judgment functioned as moral postulates of reason. In other words, they helped to safeguard against moral anarchy in Kant’s system.

Kant’s Copernican Revolution in philosophy maintained that we have knowledge of things in the natural sphere as they appear to us, as the categories of the mind interpret sense experience. In that sense, we have objective knowledge. Nothing equivalent could be maintained in the moral and aesthetic spheres. Morality and aesthetics are in the eye of the beholder, albeit according to rational constraints, but apart from the mind’s categories which are limited to the natural domain.

In addition to these dividing line considerations, one must also account for nature being causally and mechanistically construed, and human value being construed in terms of moral freedom, or the causality of freedom. This being the case, it would appear that the realms of natural determination and moral freedom are divorced in Kant’s thought. The only seeming solution is to bridge the gap through artistic genius. But will this work? Here I call to mind Simon Critchley’s reflection on Kant’s critical philosophy:

How is freedom to be instantiated or to take effect in the world of nature, if the latter is governed by causality and mechanistically determined by the laws of nature? How is the causality of the natural world reconcilable with what Kant calls ‘the causality of freedom’? How, to allude to Emerson alluding to the language of Kant’s Third Critique, is genius to be transformed into practical power? Doesn’t Kant leave human beings in what Hegel and the young Marx might have called the amphibious position of being both freely subject to the moral law and determined by an objective world of nature that has been stripped of any value and which stands over against human beings as a world of alienation? Isn’t individual freedom reduced to an abstraction in the face of an indifferent world of objects that are available to one – at a price – as commodities? (Simon Critchley, “What is to be Done? How to respond to nihilism,” in Continental Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), page 76.)

Whether one finds Kant convincing, or a last ditch and failed effort to safeguard human value from extinction, one cannot help but marvel at the great pains to which he goes in safeguarding meaning in the universe through his critical philosophy. Jesus even plays an important role as the great moral teacher. But if I am correct, Kant never mentions Jesus by name. As with the moral postulates of reason, does a Hellenized Jesus or Christ principle serve as a stopgap measure to safeguard Western morality, especially for white enlightened men like Kant? Here I recall J. Kameron Carter’s book, Race: A Theological Account, wherein he argues that Kant’s “transcendental” categories are in fact little more than attempts to universalize white European cosmopolitan subjects as normative not just historically, but also in terms of natural epistemological structures. This piece also presents a very balanced and fair appraisal of Kant’s relationship to racism. But try as many enlightened white philosophers and theologians might, can the God of the Bible and Jesus of Nazareth really serve as moral placeholders for Kant, or for other members of his philosophical-theological guild? Then again, would the biblical God and Jesus of Nazareth even want to serve as moral placeholders?

No doubt, some pious souls will fear there is virtually nothing, or nothing at all, to keep our humanity from sliding down into the ugly ditch of barbarism, or to keep us from getting crushed by the materialistic cogs in the machine of Newtonian-esque mechanism. In a last-ditch effort, they may look to the Hellenized God and to the Christ principle to create formidable stopgap measures that maintain their cultural hegemony. Perhaps, though, the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, and of Moses, in addition to Jesus of Nazareth, have no interest in complying with such drastic efforts and aspirations. As far as the God revealed in Jesus is concerned, maybe it would be more meaningful to hang in the alienated air on a cross, embracing the nihilist cry of despair on the lynching tree, just as Jesus did.