As radical and as progressive as they were in their historical contexts, Kant, Hegel and Schleiermacher may appear to many today as bourgeois, defenders of the status quo in Germanic philosophy and theology (Refer to these posts on Kant, Hegel, and Schleiermacher). Who might the “many” be, or include?

In a footnote to my recent Schleiermacher post, I reference Gary Dorrien’s discussion of Gustavo Gutiérrez’sassessment of progressivist theology. Here is Dorrien:

The disjuncture between liberationist and progressivist theologies is revealed, for Gutiérrez, in the fundamental questions that these theologies address. Modern progressive theology, beginning with Schleiermacher, has been preoccupied with questions posed by the Enlightenment, historical criticism, science, and technology. The critical questions of unbelievers—as in Schleiermacher’s address to the “cultured critics of religion”—have set the agenda for modern theological scholarship. Gutiérrez does not criticize this intellectual tradition. His own work has been decisively influenced by the most progressive forms of modern European theology… He only observes that the problems of first-world theologies do not reflect the concerns of the marginalized people who have created liberation theology. For them, the fundamental theological questions are how to be a person and believe in a personal God in a world that grotesquely oppresses their personhood. “The question is now how we are to talk about God in a world come of age,” Gutiérrez asserts, ‘but how we are to tell people who are scarcely human that God is love and that God’s love makes us one family. The interlocuters of liberation theology are the nonpersons, the humans who are not considered human by the dominant social order—the poor, the exploited classes, the marginalized races, all the despised cultures. Liberation theology categorizes people not as believers or unbelievers, but as oppressors or oppressed.” Viewed from the perspective of the oppressed, he observes, the most cherished articles of the progressivist faith—including the liberal conception of democracy and the progressivist “opposition” to violence—often appear in a different light. Gutiérrez’s argument on the question of violence begins with the assertion that, contrary to its image, liberation theology is motivated by a profound abhorrence of violence. It is personally distressing to Gutiérrez that liberation theology is so often portrayed as a theology that advocates violence, and he is frequently challenged to defend his position by critics who presume that they “oppose violence” more than he does.[1]

We will have opportunity to analyze liberation theology in future posts. This is the reason for including this lengthy quotation at this juncture. For now, I wish to focus consideration on the questions that mainstream theology, whether of the progressive or conservative sort, often emphasize: how to talk about God in a world come of age.

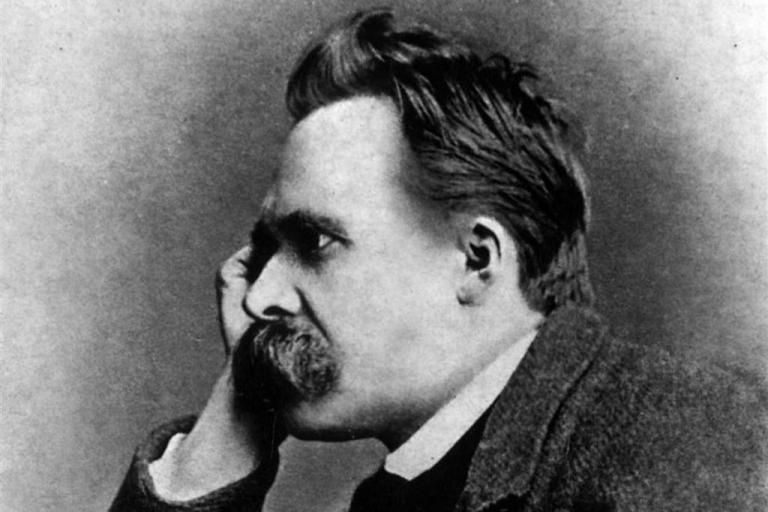

Kant, Hegel and Schleiermacher all made room for God in their novel intellectual systems. In one way or another, God played an indispensable role in safeguarding order and virtue and meaning. In contrast to these three ideological masters, the atheistic masters of suspicion removed God. God/religion is a projection (Feuerbach), an opiate (Marx), a neurosis (Freud), a dead metaphor (Nietzsche). For Nietzsche, for example, it is vital that we learn how not to talk about God. The construct is no longer useful, having lost its staying power.

If there is a problem with how Kant, Hegel and Schleiermacher approached God and religion, could it be their impulse or reflex action to try and make God relevant to the dominant social order? What happens to Jesus on this view? Does he end up serving as a moral postulate of reason, an illustration of the grand dialectical synthesis, or the apotheosis of God-consciousness latent in all who are truly cultured? Besides, making God ‘relevant’ to the dominant social order often makes God ‘irrelevant’ to the dominated social orders.

When we seek to make Jesus relevant to a system or way of life (an instinct residing deep inside all of us) rather than ‘allow’ him to speak for himself, we do violence to the incarnation. Rather than embrace the scandal of particularity like the Christian master of suspicion Kierkegaard did, we falsely generalize Jesus’ significance, turning him into a device for our own self-awakened divinization.[2] Now some might argue the same is true of liberationist theologies, claiming that Jesus is turned into a social revolutionary. This is an important for all theologians to consider—progressivists, conservatives, or liberationists.

But it does not mean that masters of suspicion today—those who no longer believe in God—can kick back, take it easy, and let life come to them. Nietzsche challenged the God-mockers in his day to take to heart the new social order that they must create in the wake of God’s death. Here’s Nietzsche’s (rather sane) madman:

How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it? There has never been a greater deed; and whoever is born after us — for the sake of this deed he will belong to a higher history than all history hitherto.”[3]

Unlike many agnostics and atheists who like to have their cake and eat it, too, Nietzsche understood well the implications of God’s death. There was no room for pragmatism (operating as if God exists), for the threat of nihilism was always right around the corner. If God is dead, and we have killed him, we must create our destiny moment by moment, for nothing is given, especially not meaning. Edward Craig reflects astutely on the matter of pragmatism and belief, contrasting Nietzsche and William James:

… James’ writing exudes a certain easy confidence that Nietzsche altogether lacked and could never have approved. His optimism, where it is found, is hard-won and precarious. He feels very keenly something of which James shows little awareness and most certainly does not emphasise, that the realisation that a belief is held for pragmatic purposes is halfway to its abandonment. Where pragmatism enters, “Nihilism stands at the door,” [taken from Will to Power, paragraph 1] and to accept nihilism and to overcome it calls for a degree of inner strength far beyond the normal. Hence the force of its competitors, as Nietzsche well knew.[4]

Whether we set out to resolve the conflict through Jesus and the resurrection from the dead, as Christians do, or the doctrine of eternal recurrence, as Nietzsche did, we are all left to tend to finding lasting meaning in our universe. This quest is by no means bourgeois, only certain ways we frame the matter.

Jesus does not approach lasting meaning and immortality by way of a grand escape that affirms bourgeois or status quo theology and philosophy. He does not deny this world, as Nietzsche claims of Christianity. Nor does Jesus deny the lowly neighbor, as Nietzsche’s Übermensch does. Rather, Jesus is the neighbor to the oppressed.[5]

Jesus’ kingdom does not provide a way out of this world and a free pass from being in solidarity with the oppressed. Rather than focusing exclusively or primarily on questions of how to make sense of God in a world come of age, Jesus would have us join God in identifying with those whose age and dignity are cut short in this world:

Fear not, little flock, for it is your Father’s good pleasure to give you the kingdom. Sell your possessions, and give to the needy. Provide yourselves with moneybags that do not grow old, with a treasure in the heavens that does not fail, where no thief approaches and no moth destroys.For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also” (Luke 12:32-34; ESV).

Say what you want of Nietzsche, and Kierkegaard while you are at it, but their critiques of Christianity, Christendom[6] and bourgeois philosophy and theology, help us reconsider and come to terms with Jesus and his kingdom come of age.

__________________

[1]See Gary J. Dorrien, Reconstructing the Common Good: Theology and the Social Order (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1990), page 107.

[2]See Søren Kierkegaard, Philosophical Fragments, ed. and trans. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985), pages 11-18.

[3]See the entire context for this statement Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science (1882, 1887) para. 125; Walter Kaufmann ed. (New York: Vintage, 1974), pages 181-82.

[4]Edward Craig, The Mind of God and the Works of Man (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), page 281.

[5]See Karl Barth’s analysis of Jesus and Nietzsche’s Dionysus in Church Dogmatics, vol. III/2, The Doctrine of Creation, ed. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1960), pages 236-242. Nietzsche speaks of Christ as a neighbor in The Will to Power: Friedrich W. Nietzsche, The Will to Power, ed. Walter Kaufmann, trans. Walter Kaufmann and R. J. Hollingdale (New York: Random House, 1967), pages 107-108. For Nietzsche’s opposition of Dionysus to the Crucified, see Friedrich W. Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, ed. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Vintage Books, 1969), pages 332-335.

[6]See Søren Kierkegaard, “The Attack Upon ‘Christendom,’” in A Kierkegaard Anthology, ed. Robert Bretali (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), pages 464–465. See also Bretali’s editorial comments that introduce Kierkegaard’s essay; according to Bretali, Kierkegaard will later claim that he exaggerated his critique to challenge the status quo for the sake of “restoring the general balance.” (page 435).