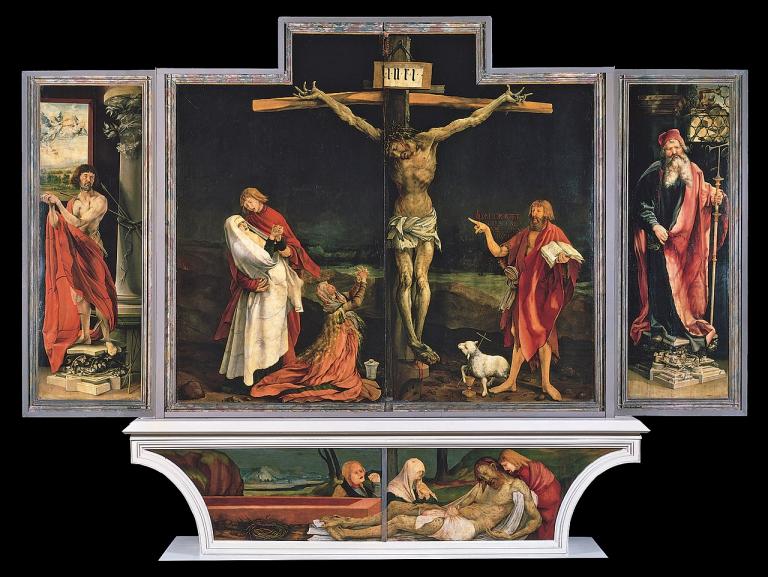

If you could be God, what kind of God would you be? A God of power like Zeus, or of heathen revelry like Dionysus? Would you ever consider becoming the God who becomes a lowly neighbor who is pushed off history’s stage with all who are marginalized? While Nietzsche’s version of Dionysus is not given to debauchery, but tragic heroism, nonetheless, the will to power doctrine entails that his Dionysus contends against Jesus, the crucified Messiah, who is the lowly neighbor.

Nietzsche provides us with the doctrine of humanity come of age, Renaissance man, the “final European,” as Karl Barth refers to him. Nietzsche repudiates the crucified God, who is the neighbor. In Jesus’ place, one finds Dionysus and the Übermensch, who for Nietzsche is the true goal of humanity.[1]

One could make a case that Barth developed his theology as a response to Nietzsche and Ludwig Feuerbach. Barth writes that the question posed by Feuerbach to the theology of Schleiermacher and his disciples concerns “whether and how far religion, revelation, the relation between God and man, can be made understandable as a predicate of man. Theology had let itself be driven by the upsurge of a self-glorifying and self-satisfied humanism from Pietism over the Enlightenment to Romanticism.” In the end, was not the result “the apotheosis of man?”[2]

The move to displace God did not begin with the masters of suspicion like Nietzsche and Feuerbach, though. According to the biblical narrative, it began in Genesis chapter 3. Our primal story entails wanting to be like God without God–autonomy. According to the New Testament, only Jesus operates differently. He takes on himself our isolation. Even though he is in the nature of God, he did not consider deity something he had to grasp, and so made himself nothing for others. As a result, God glorified him above all others. No wonder, St. Paul instructs us to consider Jesus. He is the model for considering others better than ourselves and so live in a manner pleasing to God.

Now Nietzsche believed that the Crucified God is the church’s projected attempt at becoming God. How so? In his mind, the clergy seeks to gain control over others who should lay their lives down for the church just as Jesus laid down his life. In Nietzsche’s estimation, it is an insidious, but quite successful move to put down the aristocrats and gain power over the people (Refer here for a helpful treatment of Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil and On the Genealogy of Morals, Essay III). Here’s Nietzsche’s charge of projectionism: “God on the cross—are the horrible secret thoughts behind this symbol not understood yet? All that suffers, all that is nailed to the cross, is divine. All of us are nailed to the cross, consequently we are divine. We alone are divine. Christianity was a victory, a nobler outlook perished of it—Christianity has been the greatest misfortune of mankind so far.”[3] But what if the church does not seek to gain power through the guise of servanthood in pursuit of divinity, but release and share power with those in need and those in the margins–from the margins, just like our Lord, and like his servant Timothy. Paul says of his son in the faith that Timothy is unique in this regard: “For I have no one like him, who will be genuinely concerned for your welfare. For they all seek their own interests, not those of Jesus Christ” (Philippians 2:20-21; ESV). The only way to counter Nietzsche’s charge of projectionism is not to project false testimony, but embody cruciform witness through participation in Christ Jesus’ life.

For Barth, God demonstrates Jesus’ deity in his divine humiliation, not our humiliation. God exalts humanity in Jesus’ ascent, just as he undertakes the far journey of divine isolation and humiliation in his descent.[4] The only way to counter Nietzsche and Feuerbach’s charge is not simply to observe Jesus’ story, but to embrace it as our own. And why would we want to do so? It is because Jesus’ story is by no means a projection of self-love in the ceaseless, joyless attempt to knock off the aristocracy and become God in their place. Rather, Jesus’ story is the ultimate revelation of selfless, unceasing joyful love through which God shares the divine life with us for all eternity.

_______________

[1]Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, vol. III/2, The Doctrine of Creation, ed. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1960), page 236. See Barth’s entire treatment of Nietzsche on this subject on pages 231-242. Nietzsche speaks of Christ as a neighbor in his work, The Will to Power. See Friedrich W. Nietzsche, The Will to Power, ed. Walter Kaufmann, trans. Walter Kaufmann and R. J. Hollingdale (New York: Random House, 1967), pages 107-108. See also Barth, Church Dogmatics, vol. III/2, pages 239, 240. For Nietzsche’s opposition of Dionysus to the Crucified, see Friedrich W. Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, ed. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Vintage Books, 1969), pages 332-335. See also Barth, Church Dogmatics, vol. III/2, pages 236-242. Here’s Walter Kaufmann’s explanation of this particular Nietzschean take on Dionysus: “Looking for a pre-Christian, Greek symbol that he might oppose to ‘the Crucified,’ Nietzsche found Dionysius. His ‘Dionysius’ is neither the god of the ancient Dionysian festivals nor the god Nietzsche had played off against Apollo in The Birth of Tragedy, although he does, of course, bear some of the features of both. In the later works of Nietzsche, ‘Dionysius’ is no longer the spirit of unrestrained passion, but the symbol of the affirmation of life with all its suffering and terror. ‘The problem,’ Nietzsche explained in a note that was later included in the posthumous Will to Power (section 1052), ‘is that of the meaning of suffering: whether a Christian meaning or a tragic meaning…. The tragic man affirms even the harshest suffering.’ And Ecce Homo is, not least of all, Nietzsche’s final affirmation of his own cruel life.” Walter Kaufmann, “Editor’s Introduction” to Ecce Homo, in Basic Writings of Nietzsche, edited by Walter Kaufmann (New York: The Modern Library, 1992), page 665. See also Nietzsche’s account of the tragic figure’s embrace of all of life as it is on pages 762, 765, 783, and 787 of Ecce Homo.

[2]Karl Barth, “Ludwig Feuerbach,” in Theology and Church: Shorter Writings, 1920-1928, with an introduction by T. F. Torrance, trans. Louise Pettibone Smith (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1962), page 227. See also Ludwig Feuerbach, Lectures on the Essence of Religion, trans. Ralph Manheim (New York, Evanston, and London: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1967), page 17.

[3]See the whole context of this statement in Friedrich Nietzsche, The Antichrist, in The Portable Nietzsche, ed. Walter Kaufmann (New York: The Viking Press, 1968), pages 633-644.

[4]See Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics. vol. IV/1, The Doctrine of Reconciliation, ed. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1956); Church Dogmatics. vol. IV/2, The Doctrine of Reconciliation, ed. by G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance. (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1958).