You may be familiar with David Hume’s famous puzzle about the problem of evil that appears in his Dialogues. A variation of it goes something like: If God is all good, all-knowing and all-powerful, where does evil come from?[1]

While such questions as this one certainly have their place in any philosophical discussion on the topic, it is worth pointing out that neither Christian Scripture nor the Church Fathers generally tended to frame the conversation in this way. For Scripture and the Fathers, the question is not so much where does evil come from, but where is it going, and how will God address it?

The other night, The Institute for Cultural Engagement: New Wine, New Wineskins hosted a forum titled “God and Evil: A Panel on Theodicy” (you can find the video for the forum at the close of this blog post). Scholars of diverse perspectives engaged the subject of evil from classical theism to process theology or philosophy. While each contributor provided invaluable reflections, a point made by my colleague Derrick Peterson merits consideration in this post. Peterson claimed that in the modern period, questions pertaining to Christology and how Jesus addresses evil faded from consideration. A more abstract notion of deity and God’s engagement of the world emerged and dominated the conversation. Peterson referenced a statement by Kenneth Surin that bears upon this blog entry: “Virtually every contemporary discussion of the theodicy question is premised … on an understanding of God overwhelmingly constrained by the principles of seventeenth and eighteenth century philosophical theism.”[2]

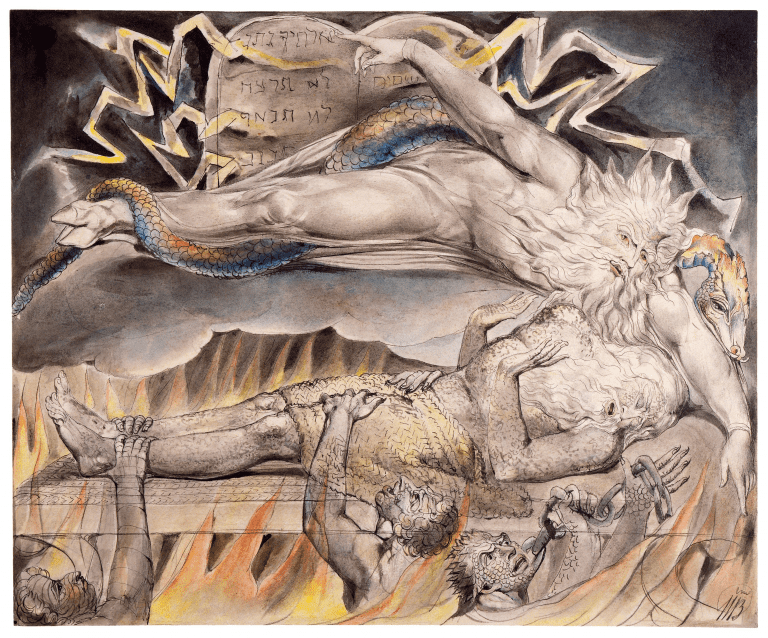

The point here is not to discount the modern treatment of evil and development of theodicies to account for the various factors. But we should note that it would be anachronistic to expect the same kinds of questions and answers from Scripture or pre-modern theology. Their reflections were far more concrete. Take, for example, Job’s struggle with God. God never answered Job’s question about why bad things happen to good people. Rather, God disclosed who he is as the Ancient of Days, who is all-good, all-wise, and all-powerful. Moreover, God resolved the horrific ordeal by restoring Job and enriching his life beyond what he had previously experienced.

When we turn to the New Testament, we find that God confronts evil head on through the story of Jesus, in particular, his death and resurrection. In seeking to provide comfort and encouragement for believers in Corinth, Paul writes,

When the perishable puts on the imperishable, and the mortal puts on immortality, then shall come to pass the saying that is written:

“Death is swallowed up in victory.”

“O death, where is your victory?

O death, where is your sting?”The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law. But thanks be to God, who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ.

Therefore, my beloved brothers, be steadfast, immovable, always abounding in the work of the Lord, knowing that in the Lord your labor is not in vain. (1 Corinthians 15:54-58; ESV)

Our labor is not in vain because God’s confrontation of evil is not in vain. God resolves the problem of evil by bringing an end to it in Jesus, so that our future bound up with faithful service is secure.

Those who control the terms of debate control the debate. If we come to terms with the biblical account and pre-modern theology, we will find that not only does Jesus’ story control the debate, but also his confrontation of evil completely controls and destroys it. Jesus is our hope.

_______________

[1]Refer here: Paul Russell and Anders Kraal, “Hume on Religion,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2017/entries/hume-religion/>.

[2]Kenneth Surin, Theology and the Problem of Evil (New York: Blackwell, 1986), page 4.