Have you ever heard the phrase “relational martyrdom ”? Well, I hadn’t, until my colleague Becca Jones mentioned it to me. Becca Jones is the Director of Student Counseling & Wellness at Multnomah University. Becca and I discussed this topic yesterday. The entire discussion was recorded and will appear at New Wine, New Wineskins’ YouTube channel over the coming days. A clip from the video is included at the close of this blog post. Becca, others and I will be discussing this theme in a few days during “Wellness Week” at Multnomah.

Becca defined relational martyrdom in the following terms: “Often people who serve to the point of overextending themselves and crossing boundaries struggle to say ‘no’ in their various relationships for fear of being selfish or greedy. They view this as an act of martyrdom or service when it can often be fear-based, where they are afraid to say ‘no,’ to disappoint, miss out, or be perceived in a certain way, which can actually be self-serving.”

Becca’s point that failing to say “no” can be “self-serving” may appear counter-intuitive. But think of it. If we refuse to say “no” because we want people to like us, then our real concern appears to be about self-preservation, albeit in a manner where the other person(s) dictate to us our sense of identity or worth.

Becca added that “having boundaries, and saying ‘no’ is not selfish, and is in fact often an act of generosity.” Generosity? Here again, the counter-intuitive wheels in our heads may be turning. How can saying “no” or having boundaries be a sign or expression of generosity?

For one, saying “no” does not allow the other person to operate beyond their appropriate boundaries. When people over-extend their reach and have control over us, they are no longer operating as fellow humans, but as demons who devour humans, unlike God who frees us to be in healthy relationships. “Demons”? Yes, indeed. Humans can easily function as demons. C.S. Lewis reflects upon this matter in his account of the demonic dimension in The Screwtape Letters. Lewis argues that it does not really matter if his readers believe in the reality of his demons, for what his literary monsters represent are fallen humans, throwing “light from a new angle on the life of men.”[1] Both Lewis’s demons and fallen humans are incurvatus in se, which signifies that they are bent or turned in on themselves. To the demons “a human is primarily food.” As the demon Screwtape says, “our aim is the absorption of its will into ours, the increase of our own area of selfhood at its expense.”[2] If, by chance, the human slips through their grip, the demons ravage or devour one another.[3] By saying “no” to such demonic inhumanity, we are being generous. We are not only seeking to safeguard from abuse and victimization, but also trying to preserve others from losing their humanity through victimizing others.

In view of the demonic involving man’s inhumanity toward others, there are situations where we have no control over how people treat us, and all that is left to us is to say “no” to responding out of keeping with sound identity and character. In that way at least, we remain victorious rather than play into victimization. As Holocaust survivor Victor Frankl argued in Man’s Search for Meaning: “everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to chosen’s one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”[4] Having noted those extreme holocaust-like situations where people are taken captive beyond their control, we should do everything in our power to put an end to relational forms of martyrdom by saying “no” and exiting the ordeal. Women and men and children should do everything possible not to remain in abusive situations. We must do everything possible to aid them in their escape rather than encourage them to stay,[5] even if it produces suffering for us.

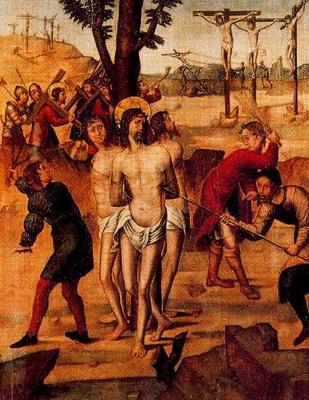

Of course, there are many situations where we find ourselves unable to bring about good resolutions to ordeals, and where we feel powerless to help others. While we should do our part courageously, cogently and compassionately, we must also depend on God and encourage others to seek God’s help, as well as our own, even while they practice resilience and foster their own forms of human agency. Thus, in addition to serving as an act of generosity, learning to say “no” to functioning as a surrogate deity for another person is a sign of humility. We all have limitations, as we are finite beings. Thus, there are times when saying “no” can help guard against inordinate dependence on us. Certainly, we are called to help others in appropriate ways to the best of our ability and strength, but ultimately, we need to help people depend on God and find their identity in Christ. Jesus suffered for everyone’s sins. He is the wounded healer. We are all in need of him. He already died for people’s sins. It is not our place to be martyrs with messiah complexes who die for others’ sins and take them upon ourselves as if we are vicarious, sacrificial lambs.

In addition to generosity and humility, learning when to say “no” can be a sign of genuine and healthy relationality. The problem with relational martyrdom is that it is not relational enough. Of course, there are times when suffering is vitally important in our relationships with God and others, including spouses, friends, and even strangers. The question is not suffering, but the kind of suffering. We need to say “no” to suffering that promotes suffering for suffering sake.

It has become clear to me over the years that suffering is not in itself virtuous. Suffering can draw us to Jesus if our aim is relationship with him, not suffering or martyrdom, as such. Paul wanted to participate in Jesus’ life, suffering, death, and resurrection. Paul writes while imprisoned for his faith:

Indeed, I count everything as loss because of the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord. For his sake I have suffered the loss of all things and count them as rubbish, in order that I may gain Christ and be found in him, not having a righteousness of my own that comes from the law, but that which comes through faith in Christ, the righteousness from God that depends on faith—that I may know him and the power of his resurrection, and may share his sufferings, becoming like him in his death, that by any means possible I may attain the resurrection from the dead (Philippians 3:8-11; ESV).

Shared suffering can bring people together, though it can also tear them apart. Paul’s aim was to participate in Jesus’ entire life story, the good and the bad times, not simply the pleasant parts. Why? Because he deeply loved Jesus and wanted to be vitally and relationally connected to him in whatever way possible. Vital relational connection is what makes suffering–including martyrdom for Christ–meaningful, not irrational.

Similarly, 1 Corinthians 13 claims that love must be what defines every aspect of our lives, including suffering. Again, Paul writes: “ If I give away all I have, and if I deliver up my body to be burned, but have not love, I gain nothing” (1 Corinthians 13:3; ESV). Surrendering one’s body to the flames is not meritorious. Rather, the love within us that comes from the Spirit who is the giver of the gifts (1 Corinthians 12 and 14) is what God finds pleasing.

As we are discussing the triune God, it is worth pointing out there were times that Jesus avoided suffering, for his hour had not yet come (John 8:20). But whenever Jesus did suffer, it was because he sought to live in keeping with his Father’s will for his life: “Father, if you are willing, remove this cup from me. Nevertheless, not my will, but yours, be done” (Luke 22:42; ESV). Jesus never lost his relational identity in suffering either. He remained grounded in his relationship with the Father. His identity was framed in relationship with the Father who himself suffered loss in giving up his Son (John 3:16).

Learning to say “no” at times can help us guard against relational martyrdom. This post reflects on how saying “no” can express generosity, humility, and relational security. They are not exhaustive, but are very important factors to account for, express, and embody when saying “no” for the sake of moving toward relational wholeness.

_______________

[1]C.S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters, with Screwtape Proposes a Toast, revised edition (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1982), page xii.

[2]Lewis, The Screwtape Letters, page 37.

[3]See Lewis, The Screwtape Letters, pages 145-146, 149.

[4]Victor E. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning, with a foreword by Harold S. Kushner and an afterword by William J. Winslade (Boston: Beacon Press, 2006).

[5]Unfortunately, all too often women are encouraged to stay in abusive marriages because of a distorted view of Scripture’s sacred regard for marriage or a faulty interpretation of the word “submit,” which is often taken wrongly in our day to support male superiority and heavy-handed-ness.