The Feast of the Transfiguration occurs on August 6. Still, today we join with others across the globe in highlighting the Transfiguration as the culmination and close of Epiphanytide and transition to Lent.

All three Synoptic Gospels highlight the Transfiguration. We will focus on its appearance in Matthew chapter 17. As a precursor, Matthew 16 includes Jesus’ confession of Jesus as the Christ, Jesus’ rebuke of Peter for resisting Jesus’ claim that the Lord must suffer and be killed by the authorities before rising from the dead, and Jesus’ call for his disciples to carry their crosses and follow him (Matthew 16:13-28). The chapter closes with these words:

For the Son of Man is going to come with his angels in the glory of his Father, and then he will repay each person according to what he has done. Truly, I say to you, there are some standing here who will not taste death until they see the Son of Man coming in his kingdom.” (Matthew 16:27-28; ESV)

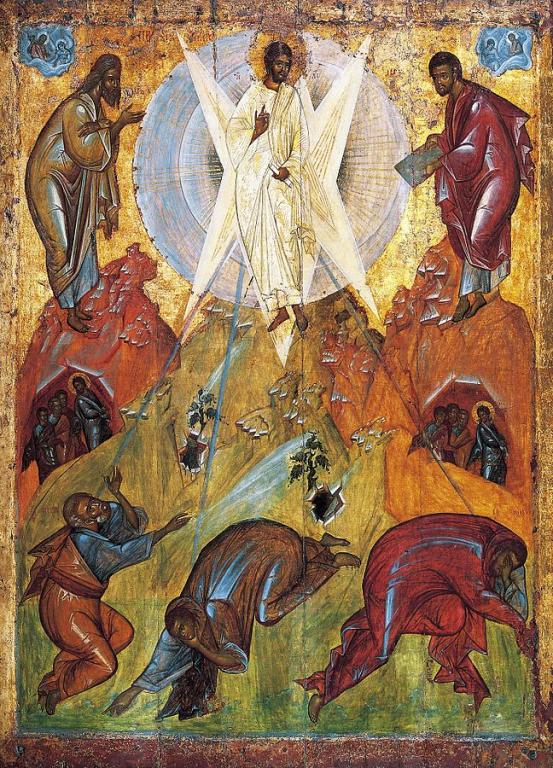

Chapter 17 begins by ushering in the Transfiguration scene, according to which Jesus takes Peter, James and John with him onto a mountain. There Jesus reveals his glory to his disciples. Moses and Elijah appear and talk with him, no doubt highlighting that Jesus is the fulfillment of the Law of Moses and the Prophets who wear Elijah’s mantle (Matthew 17:1-3).

Before we proceed further with the text, it is important to highlight the title of this essay: this account transitions the church from Epiphanytide, which accounts for numerous manifestations of Jesus’ glory, to Lent, which is the season preparing Jesus’ people for the Lord’s passion and inviting us to participate with him in his suffering. This being the case, the Transfiguration serves as a sign of encouragement, as it follows on the heels of Jesus’ prediction of suffering and death, as well as his call to his disciples to take up their crosses and follow him. Jesus promises that some of those with him would see his future kingdom glory before they experience death. As Pastor Ralph Smith writes,

Crucifixion for Jesus and the cross for His followers — this was a new teaching, as hard to accept as to understand. Thus, Jesus offered words of encouragement. Some of those standing there would see the kingdom of God (Matthew 16:28; Mark 9:1; Luke 9:27). Though He had spoken of death by the cruel cross, Jesus had not cancelled the kingdom program.

The Transfiguration serves as a sign of encouragement as it foreshadows Jesus—the Son of Man—coming in his kingdom glory at the end of the age (Matthew 16:28). We must keep this account before us, as we come down the mountain with Jesus and the three disciples, and as we join them on the path to Golgotha.

Of course, as is well known, not everyone accepts the traditional account of Jesus coming in his glory at the end of the age. The great liberal biblical scholar/historian, philosopher and missionary medical doctor, Albert Schweitzer conceived Jesus’ greatness differently than orthodox theology. His take is certainly one possible option, that is, if the New Testament vision of Jesus’ bodily return in glory to sum up history is wishful thinking:

There is silence all around. The Baptist appears, and cries: “Repent, for the Kingdom of Heaven is at hand.” Soon after that comes Jesus, and in the knowledge that He is the coming Son of Man lays hold of the wheel of the world to set it moving on that last revolution which to bring all ordinary history to a close. It refuses to turn, and He throws Himself upon it. Then it does turn; and crushes Him. Instead of bringing in the eschatological conditions, He has destroyed them. The wheel rolls onward, and the mangled body of the one immeasurably great Man, who was strong enough to think of Himself as the spiritual ruler of mankind and to bend history to His purpose, is hanging upon it still. That is His victory and His reign. Albert Schweitzer, The Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of its Progress from Reimarus to Wrede, translated by W. Montgomery (London: A. & C. Black, Ltd. 1910), pages 370-371.

Contemporary New Testament scholar and biblical historian, N.T. Wright provides a different assessment, and one with which I resonate. It is worth quoting his summation at length:

Suppose that, after all, the ancient Jewish story of a God making the world, calling a people, meeting with them on a mountain – suppose this story were true. And suppose this God had a purpose for his world and his people that had now reached the moment of fulfillment. Suppose, moreover, that this purpose had taken human form and that the person concerned was going about doing the things that spoke of God’s kingdom coming on earth as in heaven, of God’s space and human space coming together at last, of God’s time and human time meeting and merging for a short, intense period, and of God’s new creation and the present creation somehow knocking unexpected sparks off one another. The earth shall be filled, said the prophet, with the knowledge of the glory of YHWH as the waters cover the sea. It is within some such set of suppositions that we might make sense of the strangest moment of all, at the heart of the narrative, when the glory of God comes down not to the Temple in Jerusalem, not to the top of Mount Sinai, but onto and into Jesus himself, shining in splendor, talking with Moses and Elijah, drawing the Law and the Prophets together into the time of fulfillment. The transfiguration, as we call it, is the central moment. This is when what happens to space in the Temple and to time on the sabbath happens, within the life of Jesus, to the material world itself or rather, more specifically, to Jesus’s physical body itself. N.T. Wright, Simply Jesus: A New Vision of Who He Was, What He Did, and Why He Matters (New York: HarperOne, 2011), pages 142-143.

Apart from the resurrection, the Transfiguration does appear as the “strangest moment of all.” Indeed, it “is the central moment” in “the heart of the narrative.” It highlights the fact that biblical history—and so, the church calendar that reflects it—comes to a culmination in Jesus standing on the mountain in his unveiled glory.

At some point, , though, we have to come down from this climax point of Jesus’ glorious manifestation on the mountain. We must take note of the reality that it is not simply biblical scholars and historians who debate Jesus’ identity and mission. The New Testament accounts reveal that the original disciples struggled, too, just as we all do. Not only does Peter wrongly rebuke Jesus for prophesying his own death (Matthew 16:22), but also this same Peter wanted to erect booths in honor of Jesus, Moses and Elijah. In effect, Peter mistakenly put them on the same level. Whereas Jesus rebuked Peter for standing in the way of his cross (Matthew 16:23), there on the mountain God silenced Peter:

And Peter said to Jesus, “Lord, it is good that we are here. If you wish, I will make three tents here, one for you and one for Moses and one for Elijah.” He was still speaking when, behold, a bright cloud overshadowed them, and a voice from the cloud said, “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to him” (Matthew 17:4-5; ESV).

How were Peter, James and John to process what they had experienced? For a time, they would have to keep it to themselves. As they descend the mountain, Jesus commanded them to tell no one of the vision they had seen on the mountain until after he rises from the dead (Matthew 17:9). Not only do they appear to have kept it quiet for a time, but they may even have forgotten that the Transfiguration occurred or was nothing more than a daydream. How could those who had witnessed the revelation of Jesus’ unveiled glory be hiding in fear and despair after Jesus’ death unless they had forgotten or had written it off as illusory? They are a lot like the rest of us, as we move from Sunday worship to the daily grind in the valley below every week.

Jesus and the three disciples get a more immediate reality check when they come down the mountain and witness firsthand the other disciples’ lack of faith. The disciples who remained behind in the valley below could not cast out a demon from a boy because of their “little faith.” Jesus appears exasperated with them before stepping in, rebuking the demon, casting it out, and miraculously healing the boy (Matthew 17:14-21).

How often do we fail to trust in the Lord, even after he has manifested his glory to us again and again? How often do we bring Jesus down to the level of great prophets like Moses and Elijah, or award greater significance to Jesus because of famous people sharing the limelight with him? How often do we fail to account for the fact that whether Jesus veils or unveils his glory, he is the same Lord? How often does the manifestation of Jesus reveal not only Jesus, but also the state of our own hearts? How often does the suffering that awaits Jesus and those who follow him take our minds off the glory of his kingdom to come?

In the light of such questions involving our struggles with faith, may we pray that the Spirit of God transfigure—that is, transform and revolutionize—our hearts and imaginations. In view of the Transfiguration, may we not lose sight of our hope in the coming of Jesus’ kingdom in its fullness when we come down the mountain this week and move forward to Lent.