The Book of Esther does not mention God anywhere, but it is obvious that divine providence permeates the book. God preserves the Jewish people while under hostile Gentile rule in a foreign land. The Fast of Esther and Purim, which the Book of Esther documents, highlight God’s people’s suffering and deliverance from their enemies in the Persian Empire.

Whether it is providential or coincidental, the Fast of Esther and Purim overlap with the Christian season of Lent and International Women’s Day in 2020. Like Esther’s Fast and Purim, Lent also entails fasting in keeping with Jesus’ suffering for the deliverance of God’s people. International Women’s Day with its emphasis on gender equality, women’s achievements and confrontation of inequality immediately precedes the Fast of Esther and Purim in 2020, as it falls on March 8th. Esther’s Fast occurs on March 9th and Purim begins on the night of March 9th and runs through the 10th this year. Purim occurs every 14th day of the Hebrew month of Adar, which is at the end of winter or early spring.

Much has been made of Esther’s import for women’s rights. The book focuses primarily on the providential protection of the Jewish people under oppressive foreign rule, as noted above. Even so, it bears import for Jewish and Christian feminist concerns and advocacy for women and recognition of their accomplishments while enduring and confronting patriarchy over the centuries up to the present day. This entry will highlight certain features of Esther as a Jewish and Christian canonical book, including Esther’s Fast and Purim, that features God’s people’s liberation and bear upon women’s dignity and equality.

Any fair engagement of a particular text must account for its argument and context rather than run roughshod over them with an alternative agenda and in an anachronistic manner. Esther is not first and foremost about contending against patriarchy. Nor does it present our heroine as an ancient identical twin of a self-avowed modern western feminist. The same would be true for the canonical gospels’ purpose(s) about Jesus’ aim and how the women express their agency in an ancient middle near-eastern patriarchal world. Scripture is not made of one seamless cloth regarding women either. One finds in Jewish Scripture and tradition an evolution of thought enhancing greater respect and affirmation of women’s status as equals.[1] We find this dynamic at work in Esther.

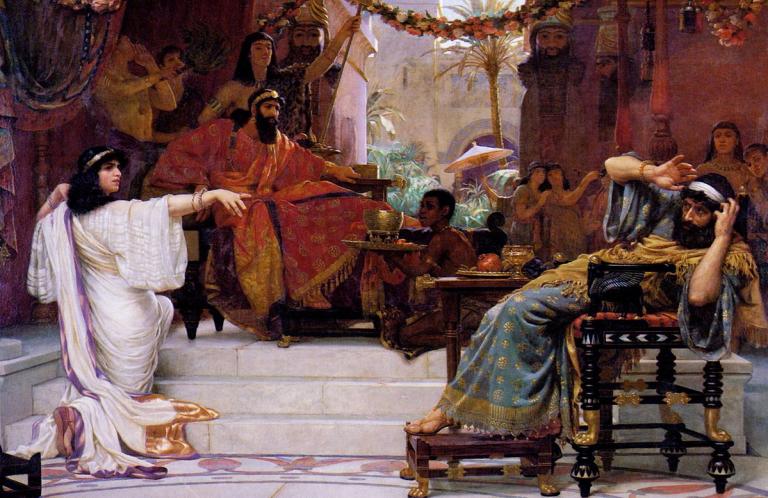

The Book of Esther offers various portrayals of women. Take for example Vashti’s strong resistance to the king’s command to entertain his guests. Her refusal leads to her dethronement. Compare her with the young maiden Esther as she makes her appearance in chapter 1. Whereas Vashti is defiant (Esther 1:10-12), Esther is compliant (Esther 2:1-18), as she is prepared to visit the king’s chamber in view of his selection of a queen to replace the deposed Vashti. Still, Esther evolves as a person. At first, she takes orders from the royal court (Esther 2:8-18) and her relative and patron Mordecai (Esther 2:10, 20; 4:8). But later she engages Mordecai dialogically as an equal (Esther 4:10-14), and then goes so far as to give him orders as the heroine of her people (Esther 4:15-17). Esther also goes before the king without an invitation, which could get her killed (Esther 4:8-17). She risks all in order to denounce the evil royal official Haman and advocate for her people’s liberation (Esther 7-8).

No matter how one views the subject, women’s status was precarious in the Persian empire, as illustrated in the treatment of Vashti and Esther. The consequence of Queen Vashti’s refusal to be put on display as the equivalent of a concubine and sex object for the king’s drunken guests to gawk at lustfully was severe. She was deposed and made an object of derision. The empire’s patriarchal leaders feared that if she were not made an object lesson, other women would follow her example and refuse to submit to male rule (Esther 1:13-22). No doubt, Esther was viewed as a model replacement—beautiful and submissive (Esther 2:5-18). Like other women, including the queen herself, Esther’s likely fear and deep reservation about being an object of sexual pleasure for the king would not matter in the slightest to the reigning forces. Such was the tragic and heinous state of affairs in which they found themselves.

Some critiques of Esther portray her as “passive and devious,” according to Michael V. Fox. Fox finds such judgments “misguided.” In contrast, Fox points out how Esther underwent a metamorphosis: “Esther has a great challenge thrust upon her. In facing it, she gains three powers that could not have been foreseen from her early behavior: agency, strategy, and authority.”

As the narrative unfolds, Esther models courage in going before the mercurial king (Esther 4:11; 5:1-4), cunning in how she entraps Haman in his hubris and hatred of the Jews (Esther 5:9-14), and compassion in how she advocates for her people (Esther 4:15-17). Esther becomes a model for Jewish leadership while in bondage in exile. Regarding this matter, Fox writes,

In Esther, the author has created a model for Jews in the diaspora, who in the absence of a national state and army, must rely on their own courage and ingenuity to deal with dangers…This picture should not, however, be understood as a reassessment of woman’s stature. Rather, it is an attempt to reconceive the status of Jews in a new context.[2]

Even if the Book of Esther does not argue for a reassessment of women’s place in the ancient world, it certainly goes a long way toward opening the door to new possibilities. We should honor Esther’s accomplishments as a courageous, cunning and compassionate leader on behalf of God’s suffering people. Esther leads us forward in demonstrating human agency in contending against the objectification and oppression of people wherever it is found.

Like Jesus after her, Esther puts people’s interests above her own. As a result, she faces the very real threat of losing not only her position as queen but also her life. We find this theme of self-sacrifice in play in the Fast of Esther. The text in Esther 4 reads:

Then Esther told them to reply to Mordecai, “Go, gather all the Jews to be found in Susa, and hold a fast on my behalf, and do not eat or drink for three days, night or day. I and my young women will also fast as you do. Then I will go to the king, though it is against the law, and if I perish, I perish.” Mordecai then went away and did everything as Esther had ordered him (Esther 4:15-17; ESV).

Like Moses before her, God raises up Esther as a savior for her people Israel. Together they foreshadow Jesus who delivers his people from their bondage to sin and liberation from oppression. During Lent, Christians would do well to remember the Fast of Esther and Purim, which their Jewish brothers and sisters honor, as instituted in Esther 9:20-22:

And Mordecai recorded these things and sent letters to all the Jews who were in all the provinces of King Ahasuerus, both near and far, obliging them to keep the fourteenth day of the month Adar and also the fifteenth day of the same, year by year, as the days on which the Jews got relief from their enemies, and as the month that had been turned for them from sorrow into gladness and from mourning into a holiday; that they should make them days of feasting and gladness, days for sending gifts of food to one another and gifts to the poor (Esther 9:20-22; ESV).

May we take to heart God’s providential care for Israel and the Church. May we also honor great leaders like Esther and follow their example. You don’t need to be Jewish to honor Esther’s Fast and Purim. But you do need to believe God providentially cares for Abraham’s people. You don’t need to be a man to be a great leader of all the people or a woman to honor International Women’s Day. But you do need to stand with women in cherishing their accomplishments and confronting inequity and abuse committed against them wherever it exists.

_______________

[1]On this subject, see Judith Hauptman, Rereading the Rabbis: A Woman’s Voice, Radical Traditions (Boulder, CO.: Westview Press, 1998).

[2]In addition to Fox’s online article from which the quotes are taken, see his earlier work on which the article builds: Michael V. Fox, Character and Ideology in the Book of Esther (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1991; 2nd ed.: Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000; reprint: Eugene: Wipf & Stock, 2010). In his online treatment, Fox affirms the feminist perspective of Sidnie D. White-Crawford, as set forth in “Esther: a Feminine Model for Jewish Diaspora,” in Gender and Difference in Ancient Israel, ed. Peggy Day (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress), pages 161-177. I also reference her encyclopedia article on Esther here.