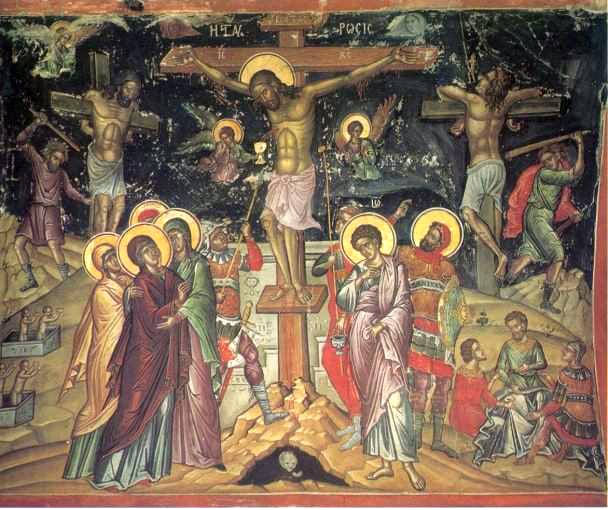

The New Testament is a very Jewish book. There is no way around it. One cannot understand what is going on anywhere in the New Testament without a grasp of what goes on everywhere in the Hebrew Scriptures. In fact, the Scriptures that Christians often refer to as the Old Testament are foundational to the New Testament and find fulfillment and perfection in the New. Good Friday—the day the church generally associates with Jesus’ death—is no exception given that Jesus’ death and resurrection are vitally connected to Passover.[1]

The canonical gospels record the significance of Jesus choosing Passover (See Exodus 12) rather than the Day of Atonement (See Leviticus 16) or one of the other two pilgrimage feasts (the Feast of Weeks and Festival of Booths; Deuteronomy 16:16) for his grand, climactic entrance into Jerusalem. N.T. Wright has this to say about Holy Week and its relation to Passover as the occasion when Jesus confronts the nationalistic piety centered in the Temple establishment:

All four gospels make clear one vital point: that Jesus chose Passover to go to Jerusalem and confront the Temple establishment with his radical counter-claim, knowing where it would lead. He didn’t choose Tabernacles or [Hanukkah]; he didn’t choose the Day of Atonement. He chose Passover, because Jesus’ understanding of his own vocation was to accomplish, once and for all, the New Exodus for which Israel had longed. Passover-imagery isn’t just miscellaneous decoration around the edge of an atonement-theory whose real focus is elsewhere. It is the flesh-and-blood reality.[2]

Jesus presents himself as the embodiment of the temple where God meets with his people. In fact, he told the Jewish authorities at the time of the first of several Passovers recorded in John’s Gospel that he would destroy the temple of his body and raise it up in three days. Thus, he had the authority to cleanse the Temple in Jerusalem (John 2:13-22; see also Matthew 21 for Jesus’ confrontation with the Temple authorities as the final Passover draws near).

Again, as Wright indicates, the canonical gospels present Jesus choosing the Passover for his climactic action of salvation for his people. Even so, the New Testament also presents a connection to the Jewish Day of Atonement or Yom Kippur, which occurs in the autumn of the year. According to the Epistle to the Hebrews, Jesus has entered the Holy of Holies as the great and sinless High Priest who has offered his own pure blood once and for all as eternal cleansing from our sin (See Hebrews 9).

It is all-too easy for us to privatize Jesus’ message and not see him as bringing deliverance for his people from established nationalistic theo-political structures that enslaved them. Such enslavement involving nationalism brought about their demise as the Jewish people sought vengeance against Rome. Their rebellion led to Rome’s destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in A.D. 70. Jesus desired to spare his people just as he seeks to spare us from all-consuming nationalistic and individualistic idols as well as vengeance that leads to self-destruction.[3] But all too often, we hide behind our idols, including holy buildings and cities, holy books and holidays of religious and national prominence and fail to account for Jesus’ presence in our midst as the replacement or fulfillment of these types, as the case may be, at the end of the age. As the Book of Revelation reminds us, God and the Lamb are the temple in the eschaton, not some building no matter how prominent or cherished: “And I saw no temple in the city, for its temple is the Lord God the Almighty and the Lamb” (Revelation 21:22; ESV).

For the sake of security and autonomy, we are tempted to stay put and not take to heart that the celebration of Good Friday and Easter overlap with Passover, the ultimate Pilgrimage feast. But as we come to terms with Jesus offering himself as the ultimate Passover Lamb[4] and leading his people in pilgrimage out of Egypt to the Promised Land, we realize we cannot stay put. We must press forward and not return to Egypt. As Hebrews 11 makes clear to us, like Abraham and other saints of old, we still have not found what we are looking for (Hebrews 11:39-40). The Promised Land, which will appear before us as the New Heavens and Earth dawn, beckons us. The Spirit and the Bride say come (Revelation 22:17).

So, don’t pass over the Passover as we celebrate Good Friday. It’s time to leave Egypt or Rome or whatever nation or city typifies Empire at a given time. And for those who have already left, don’t go back. Too much is at stake. Go forward to enter the promised rest. Remember that Jesus has conquered the grave and has authority and power and glory over all kingdoms of the world. He has won while Caesar has lost, a point that Revelation brings home. Revelation 5:12 declares: “Worthy is the Lamb who was slain, to receive power and wealth and wisdom and might and honor and glory and blessing!” (Revelation 5:12; ESV).[5] Good Friday’s here. But Easter Sunday’s coming.

_______________

[1]Religion scholar James Tabor argues that Jesus died on Thursday, not Good Friday, in the following article: “Jesus Died on a Thursday not a Friday,” Taborblog, March 20, 2016; https://jamestabor.com/jesus-died-on-a-thursday-not-a-friday/ (accessed on 3/23/2020). Regardless of the day that Jesus’ death occurred during Holy Week, the connection between Passover and Jesus’ passion and resurrection is an intimate one for the New Testament community. For another article discussing their historical connection, refer to Paula Fredriksen, “When Jesus Celebrated Passover,” Wall Street Journal, April 19, 2019; https://www.wsj.com/articles/when-jesus-celebrated-passover-11555685683 (accessed on 3/23/2020).

[2]N.T. Wright, “The Royal Revolution: Fresh Perspectives on the Cross,” Calvin College January Series, January 24, 2017; https://ntwrightpage.com/2017/01/30/the-royal-revolution-fresh-perspectives-on-the-cross/ (accessed on 3/23/2020).

[3]N.T. Wright argues that while the Jewish authorities believed Jesus’ approach and political and eschatological reinterpretation of the Scriptures and sacred symbols will lead to their destruction, it is Jesus’ reinterpretation that would lead to their preservation and victory as a people. See N.T. Wright, The Challenge of Jesus: Rediscovering Who Jesus Was and Is (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1999), pages 54-73.

[4]John the Baptist refers to Jesus as the Passover Lamb as recorded in John 1:29 and Paul does as well in 1 Corinthians 5:7. Revelation 5:6, 12 refer to Jesus as a lamb that was slain.

[5]It has been argued that “You are worthy” and “our Lord and God” greeted Emperor Domitian when he appeared in triumphal procession. The Apocalypse commandeers such language and applies it to the Ancient of Days and to the Lion who is the Lamb slain and raised bodily to new life. In effect, John seeks to convey to his readers that Caesar loses; Christ wins. See the following treatments of this theme: Robert H. Mounce, The Book of Revelation, The New International Commentary on the New Testament, revised (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 1998), pages 126-127. Hanns Lilje, The Last Book of the Bible, trans. Olive Wyon (Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press, 1957), pages 108-109; Ethelbert Stauffer, Christ and the Caesars (London: SCM Press, 1955), pages 150-159; and Robert E. Coleman, Singing with the Angels (Grand Rapids: Fleming H. Revell, 1980), pages 40-41.