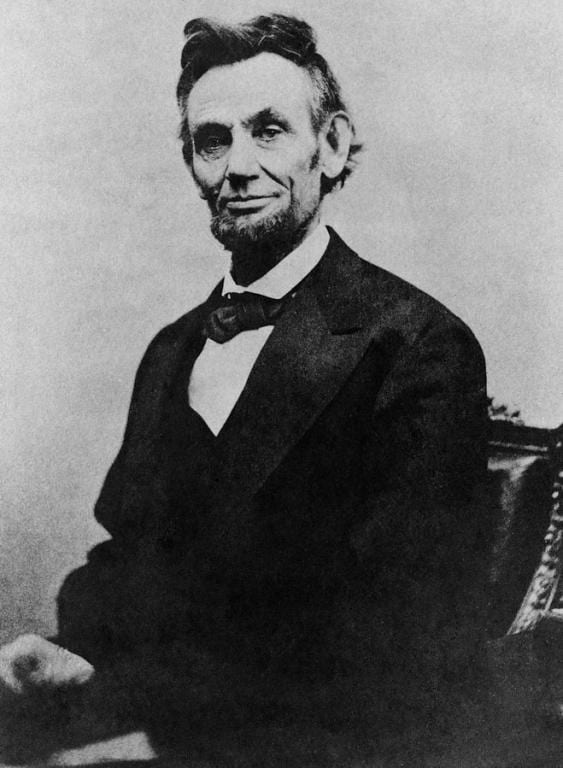

I am doing a series of blog posts related to leadership as we approach the U.S. Presidential election. This is my third blog post on the qualities of leadership that President Lincoln modeled (refer here and here for the first two posts), as discussed in Doris Kearns Goodwin’s bestselling Team of Rivals: the Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, winner of the Lincoln Prize. One of the qualities that Goodwin highlights was Lincoln’s empathy, which is constitutive of humaneness. There are so many examples and quotations from which to choose in the book, from Lincoln’s engagement with Frederick Douglass and regard for African Americans’ well-being (207, 208, 551, 553, 700), to soldiers, families of fallen soldiers, the defeated South (724, 732), those he was tasked to condemn or pardon for offenses committed during the war, and even animals (103-104).

Goodwin writes,

Lincoln’s abhorrence of hurting another was born of more than simple compassion. He possessed extraordinary empathy—the gift or curse of putting himself in the place of another, to experience what they were feeling, to understand their motives and desires. The philosopher Adam Smith described this faculty: “By the imagination, we place ourselves in his situation … we enter as it were into his body and become in some measure him.” This capacity Smith saw as “the source of our fellow-feeling for the misery of others … by changing places in fancy with the sufferer … we come either to conceive or to be affected by what he feels.” In a world environed by cruelty and injustice, Lincoln’s remarkable empathy was inevitably a source of pain. His sensibilities were not only acute, they were raw (104).

Another example comes from Lincoln’s personal interaction with Frederick Douglass. Douglass, who had been a formidable critic of Lincoln and his Administration’s policies throughout much of Lincoln’s first term, was acquainted with numerous prominent abolitionists. Still, he said of Lincoln that he was “the first great man that I talked with in the United States freely, who in no single instance reminded me of the difference between himself and myself, of the difference of color” (207). Lincoln and Douglass came to respect one another greatly. No doubt, it started with their ability to intuit deeply and perceive keenly one another’s humanity.

Long after Lincoln’s passing, the great Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy recounted his visit to the North Caucuses in 1908 where a tribal chief asked Tolstoy to tell stories of the great figures of history. Upon coming to a close, the chief stopped Tolstoy and informed him that he had forgotten to recount the greatest leader of them all—Lincoln. So Tolstoy regrouped and told the chief and his people everything he knew of Lincoln (747-748). In recounting that scene, Tolstoy went on to write that Lincoln “was a humanitarian as broad as the world. He was bigger than his country—bigger than all the Presidents together.” While “not a great general like Napoleon or Washington,” nor “such a skilful statesman as Gladstone or Frederick the Great,” “his supremacy expresses itself altogether in his peculiar moral power and in the greatness of his character” (748).

Lincoln is certainly not without his detractors, as we find among Native American accounts (refer here and here), as well as in some quarters in the South. Lincoln was a product of his time with his evolving views on emancipation, and yet transcended his time on the question of slavery more than any abolitionist in what he was able to achieve before his assassination. By no means was Lincoln divine or semi-divine, and he knew it. And perhaps we find here a key ingredient that went into the formation of his greatness. Lincoln’s early life and upbringing were of no major consequence in his own mind. He experienced so many hardships, challenges, and failures along life’s course. Given his range of experiences, as he mingled and interfaced with people of so many sectors and classes in society, he came to inhabit their longings and fears, ambitions, foibles, and struggles in a synthetic manner.

Unlike 2016 Presidential candidates Trump and Clinton who referred to one another and/or their followers as disgusting and despicable, sentiments which have only become more fever-pitched in the present presidential political season on the opposing sides, Lincoln somehow never saw himself above and apart from others, no matter what side of a conflict he was on. Certainly, his sense of his own intellectual and political powers, pursuit of greatness, and moral conviction were acute. But he never forgot where he came from and never sought to leave others behind, but to bring the country as a whole with him in pursuit of a more perfect and humane union. Empathy is a largely missing quality in our political and cultural discourse today, just like it was in 2016, as social psychologist Jonathan Haidt noted in November of that year. Empathy is not intended to eradicate moral conviction and the pursuit of justice, but to infuse such traits with the needed relational elasticity that will lead to equitable and humane justice for all and what Dr. King called the Beloved Community. This community would involve equitable rights for African Americans in solidarity with those who had once been their oppressors but who would become their companions in a “double victory,” as King articulated in his Christmas sermon of 1967. Empathy involves humility that gets us off our high moral horses so that we can see that to varying degrees, as with Lincoln’s challenge to the North and the South in his Second Inaugural, we all have a burden of guilt and responsibility to bear before the Almighty in keeping with the degree of our involvement in the conflict, including our abilities, authority, and resources at our disposal to effect moral and humane systemic change.

Lincoln was an avid student of human nature. His empathic ability to step inside others’ shoes helped him not only in perceiving and diagnosing his political opponents’ moves to strategic effect, as Goodwin notes (104), but also it helped him come to terms increasingly with the people he was called to serve, among them Northerners and Southerners, Blacks and Whites. In the midst of the horrors of war and man’s inhumanity toward man, Lincoln saw people’s humanity more than most. It’s as if he took to heart the line from Simon Bishop in one of my favorite movies (besides Spielberg’s Lincoln, of course), As Good As It Gets, “If you stare at someone long enough, you discover their humanity.”

No doubt, we can find fault with Lincoln for doing too little or not doing nearly enough. But may we not find fault with empathy and humaneness, which marks the greatest of leaders in abundant measure.