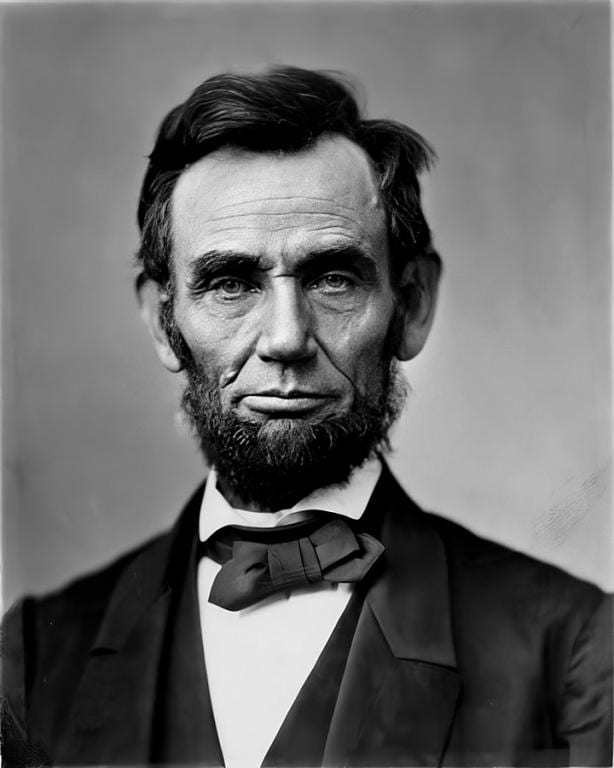

As we approach the U.S. Presidential election, I am reflecting on qualities of leadership that President Lincoln modeled. The basis for my reflections result from my reading of Doris Kearns Goodwin’s bestselling Team of Rivals: the Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, winner of the Lincoln Prize. One of the qualities that Goodwin highlights is Lincoln’s magnanimity of spirit. She notes how one of Lincoln’s chief political rivals who became one of his best friends and allies as Lincoln’s Secretary of State, William H. Seward, marveled at this trait. As he told his wife, President Lincoln’s “magnanimity is almost superhuman” (364).

The Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary defines magnanimity as “behaviour that is kind, generous and forgiving, especially towards an enemy or competitor.” We find this description on display in Lincoln’s life and speeches. Lincoln’s second inaugural address (March 4, 1865), which was delivered just weeks prior to his assassination (April 14, 1865), includes these words in closing: “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.” Certainly, Lincoln had the end of the war in mind and reconstruction of the South.

One who possesses magnanimity of spirit is not petty. A person with a malicious spirit holds grudges and seeks to do harm, get even. A leader who is characterized by magnanimity will not allow personal or public grievances to get in the way of pursuing the greater good, as we find in Lincoln’s second inaugural. Lincoln looked to reconstruction of the South after the Civil War to bring about full inclusion in the union and a “just and lasting peace” not simply for the United States, but for “all nations”. Lincoln’s assassination proved devastating to all sides in the great contest. Contrary to his murderer John Wilkes Booth’s assessment, the Richmond Whig, a publication of the South, lamented that with Lincoln’s assassination, “the heaviest blow which has ever fallen upon the people of the South has descended” (quoted in Goodwin, Team of Rivals, 744). Other forces in the victorious North would not model “charity for all” as in caring for the slain Southern soldier’s “widow and his orphan.”

Leaders with great vision for a people’s prosperity rather than their own personal gain will not allow insults to their persons and attacks on their careers to get in the way of the greater good. Lincoln was such a person. An even greater leader than Lincoln cried out from the cross on which he was hung: “‘Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.’ And they divided up his clothes by casting lots” (Luke 23:34; NIV). With the Lord Jesus’ resurrection and ascension, and the Spirit’s descent at Pentecost, his followers did not seek vengeance, but repentance and forgiveness on Jesus’ behalf for the restoration of all peoples to God. They bore the fruit of Jesus’ magnanimous spirit with malice toward none.

What spirit do we model in whatever spheres of leadership we find ourselves? Magnanimity or maliciousness of spirit? The answer to this question will make a great difference in the type of fruit we bear—profound or petty—among those under our influence, just as it will on the presidential national scene.